6-Things-Every-Healthcare-Pro-Should-Know-About-PPD

advertisement

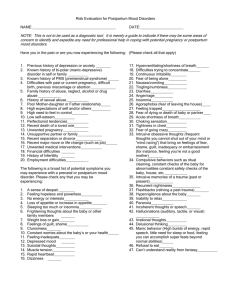

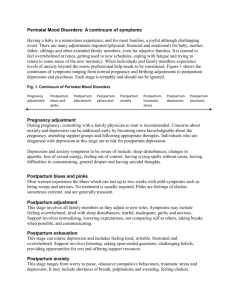

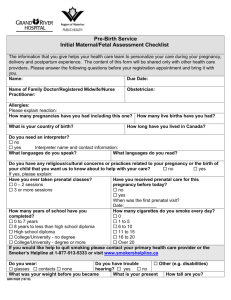

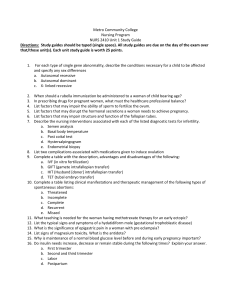

Six Things Every Healthcare Professional Should Know About Pregnancy & Postpartum Depression & Anxiety 1. Postpartum depression is only one in a spectrum of perinatal mental illnesses. One size does not fit all. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders include antepartum depression and anxiety, postpartum depression, postpartum anxiety, postpartum OCD, postpartum psychosis and postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder. One size does not fit all – there are all kinds of symptoms women may (or may not) experience in the period during pregnancy and after birth. These include: Sadness Mood swings Difficulty concentrating Irritation or anger Lack of interest in things one used to enjoy Sleep and appetite changes Panic attacks Excessive worry about the baby Disturbing thoughts about harming one’s self or the baby Mania Racing thoughts Panic attacks Headaches and stomach problems Guilt Feeling like she should never have become a mother or that she won’t be able to do it Delusions or hallucinations What matters is that the patient’s life has been significantly impacted and that her symptoms are interfering with her daily functioning and ability to take care of herself and/or her baby. (For more information on each illness and its symptoms, visit the Postpartum Support International website at http://www.postpartum.net/brief.html ) ©2009 Postpartum Progress/Katherine Stone 2. Postpartum depression can and often does happen. The Centers for Disease Control reports that 12-20% of new moms – about 1 million women in the US each year – get postpartum depression, but the truth is the number is even higher. Their data reflect only those who self report experiencing postpartum depression after live births. Many women don’t report their experiences, many women get other perinatal mental illnesses outside of PPD, and all women are susceptible to these illnesses regardless of whether they have a live birth, miscarriage, still birth or termination. Together, perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the number one complication of childbirth. 3. Symptoms can appear anytime during pregnancy and the entire first year after birth. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders can occur during pregnancy as well as any time in the 12 months after having a baby. Baby blues, a normal adjustment period after birth, normally lasts 2-3 weeks postpartum. If your patient has some of the symptoms listed above, they have stayed the same or gotten worse, and they’re past that 3-week period, they are likely no longer experiencing baby blues and may have a perinatal mood or anxiety disorder. 4. Knowing your patient’s risk factors can help you plan to prevent the illness or shorten its recovery. There are a wide variety of risk factors for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Getting a woman’s history when she first becomes pregnant can help you identify whether she is at high risk for developing one of these illnesses. Research has identified the following as some major risk factors: A personal history or family history of mental illness Previous bouts of perinatal mental illness Women who’ve had fertility treatments Women who deliver multiples Women with diabetes (type 1, type 2 and/or gestational) Women with inadequate social support. This includes immigrants who are away from their home countries, people who don’t live near family and friends, military moms whose partners are deployed, and women in strained or abusive relationships Low-income women Women who’ve experienced major childhood trauma or a recent trauma like a death in the family, a house move or a job loss Women with thyroiditis Women who’ve had serious complications in pregnancy, during the birth or with breastfeeding 5. The sooner your patient gets treatment the better. Many recent studies show that both the physical and emotional health of untreated women and their children are negatively impacted over the long term. Babies whose mothers have untreated depression during pregnancy, for instance, are twice as likely to be born pre-term, twice as likely to go to the NICU and have a 50% higher risk of developmental delay. It is important to identify sufferers as early as possible to avoid such complications where possible. ©2009 Postpartum Progress/Katherine Stone 6. It is important to screen because you can’t tell by looking. Researchers Wilen and Mounts found that when screening for depression in the health care setting is based on clinical observation alone, 50% of women suffering from depression are missed. In another study, Olsen et al found that pediatricians rarely identify maternal depression through a routine inquiry of symptoms. Furthermore, many women won’t volunteer to let you know what they’re going through. Childbirth Connection’s 2008 report finds 3 in 4 mothers with depressive symptoms had not consulted a professional about mental health problems. You have to ask the right questions, and one of the best ways to do this is with the thoroughly validated screening tools available, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Psychiatric Association, have worked together to develop a set of algorithms on the treatment of depression during pregnancy and postpartum. To learn more, visit: http://www.acog.org/from_home/publications/press_releases/nr08-21-09-1.cfm. * * * Postpartum Progress is the most widely-read blog in the United States on perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, including postpartum depression, postpartum anxiety, postpartum psychosis and depression and anxiety during pregnancy. It is written for moms, moms-to-be and clinicians. For more information about mental illnesses related to childbirth, please visit Postpartum Progress at http://postpartumprogress.typepad.com or follow us on Twitter at @postpartumprogr. ©2009 Postpartum Progress/Katherine Stone