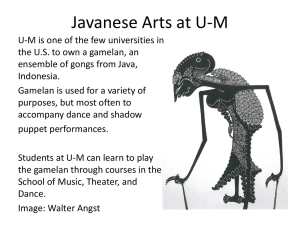

JAYA JAYA MAHABHARATHAM

advertisement