Comparing Childbirth Practices: Connections, Variations, and

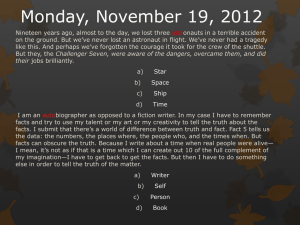

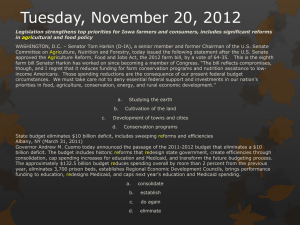

advertisement