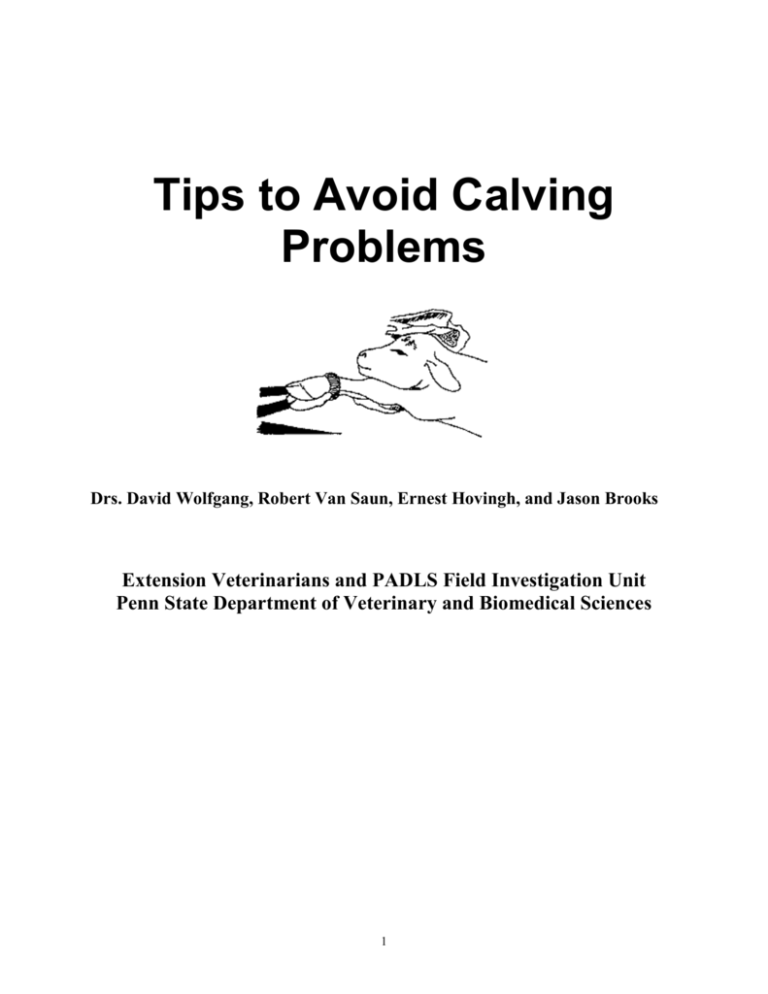

Tips to Avoid Calving Problems

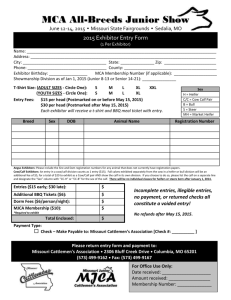

advertisement

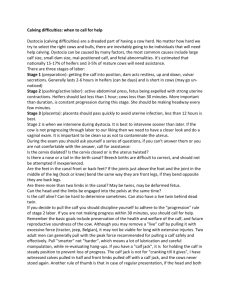

Tips to Avoid Calving Problems Drs. David Wolfgang, Robert Van Saun, Ernest Hovingh, and Jason Brooks Extension Veterinarians and PADLS Field Investigation Unit Penn State Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences 1 Tips to Avoid Calving Problems The birth of a calf can be a traumatic time for the cow, calf, and producer. Normally the cow is undergoing some major changes in diet, housing, and management all in anticipation of the upcoming lactation. Assisting the dam through the birth process in as gentle manner as possible can be extremely important in setting the stage for a productive lactation. The next few pages will outline a little about the normal calving process as well as provide a few tips on avoiding calving problems. The pelvic canal (birth canal) of the cow is composed of five bones joined together. The ilium, ischium, acetabulum, sacral vertebrae, and the pubis. Several ligaments and cartilage complete the pelvis. On the outside of the animal we see the pin bone (ilium), hook bone (ischium), and thurl (femur or hip bone that fits into the acetabulum). On the inside these make a roughly oval shaped birth canal. The canal is tipped slightly forward with the top of the canal being closer to the head than the floor of the canal. The pelvic canal is home to many other important structures. The calf must escape from the dam and not damage the bladder, rectum, major blood vessels, and a number of large nerves. Obviously, complications can arise when any of these structures are damaged. It is a miracle of life that a dam can have such a large baby and both do very well in nearly all cases. On the rare occasion that some help is needed, understanding the calving process can allow dedicated and experienced producers maximize the help and minimize the trauma. Roberts, p 4 Normal gestation (length of pregnancy) in the Holstein breed is about 282 days. If calving is 14 days early or up to 10 days late, most people consider that to be within a normal range. As the cow gets ready to calf some major changes occur in her hormones. The level of progesterone falls, estrogen, cortisol, and relaxin rise. This helps to prepare the calf for life outside the womb and prepares the dam for the birthing process. As many producers note the ligaments around the tail head soften and become more flexible about 24-48 hours before birth. The vulva will swell, relax and get longer, and become engorged with blood. Clear mucus may pass from the vulva or it may be noted on the tail. Milk or a waxy substance may be noted on the teat ends. 2 Most cows will eat less and be restless a day or so before calving. Heifers may show more dramatic signs of discomfort or lack of appetite. It is not unusual for heifers to switch their tails, rise and lie down often, or kick at their stomach. All of these signs lead up to the birth process (parturition). Birth can be divided in three stages. The first stage is related to the preparation of the dam and birth canal for the actual birth. The cervix begins to relax and open. Levels of prostaglandin increase in the blood and this begins to cause the uterus to contract and shorten. The wave like contractions of the uterus occur about every 10 to 15 minutes and each contraction can last for 15 to 30 seconds. This stage can last for various lengths of time. A common range would be 2 to 12 hours, with most animals falling between 4 and 8 hours. Heifers would take more time than cows in nearly all circumstances. Once the cervix is fully dilated, the calf should be born within 6 hours. Stage two occurs as the calf enters and passes the birth canal. In this stage each contraction occurs every two or three minutes and can last for 1 to 2 minutes. Most animals lie down during this stage. Once forceful contractions have begun cows should have their calf within 2 hours. Heifers should calve within 4 hours. Oxytocin is released as the calf enters the pelvic canal and this hormone intensifies the contractions. The allantoic membrane ruptures as the calf starts to enter the pelvic canal. This is difficult to recognize or appreciate for most people. The amniotic membranes normally can be seen before the head or feet. These membranes should not be ruptured prematurely as they allow for more forceful contractions by the dam on the entire uterus and calf. As the hooves or head begin to pass the cervix the membranes rupture with a rush of clear fluid. At this point, the dam is usually in the most active contractions of labor. The cow releases oxytocin stored in her pituitary gland. Excessive levels of oxytocin given by well meaning assistants can cause the muscles of the uterus to spasm and may actually be counter-productive. If judged to be needed, oxytocin in small doses (1 to 2 units), and repeated every 10 to 15 minutes may be more effective than larger and infrequent doses. Oxytocin should never be given to an animal if the position of the calf is not known to be correct. If given to a cow with a calf in an abnormal position a tear or rupture of the uterus can occur. In most case, this is eventually fatal to the dam. Older cows that may seem weak or unable to sustain contractions should be evaluated for milk fever. Intravenous calcium or oral calcium should be administered if signs of milk fever are present. Stage three is the passage of the placenta. Detachment of the fetal membranes is a complex mechanism to prevent blood loss and allow the uterus to return to the non-pregnant state. The immune system, nutrition, and muscular contractions combine to release the placenta. If any component of this system is not in alignment then it is likely that the membranes will be retained more than 12 hours. Ideally the membranes should be expelled within 12 hours of birth. Placentas retained for more than 24 hours are considered retained. The placenta and open cervix can cause future problems due to infection and difficulty in fertility. Even if the placenta is passed, poor muscle tone in the uterus or less than ideal hygiene in the maternity pen can lead to post calving infections in the uterus (metritis). Prolonged or severe cases of 3 metritis can cause animals to become ill, lose weight, go off feed, or become infertile. Oxytocin may be administered after calving to promote uterine contractions to help passage of the placenta. Stage of Parturition Stage I Stage II Intervention Heifer Cow 4-12 2-8 2-4 2 or less 4 hours after first contractions are observed or 2 hours after amniotic fluid (water) is seen The Difficult Calving Animals that have been in Stage 2 labor for 2 to 4 hours and have not progressed should be examined vaginally. The tail should be tied to the opposite front leg, the perineal area cleaned well with soap and warm water. A latex or plastic sleeve should be worn and every effort should be made to be clean and gentle. Commercial lubes are best but in a pinch a very mild soap can be used a lubrication. Initial exam should determine why the birth has not progressed to completion. Once the problem has been identified, a plan can be formulated. A calf will often survive for 68 hours after stage 2 has begun if it has not yet progressed into the dam’s pelvis and if the umbilical cord is not compromised. The most common problem is a mismatch between calf size and the size of the dam’s pelvis. The area around the shoulders and neck is the largest area of the calf. However, the largest width to get through the birth canal is the hip area. Either the dam or the calf can be part of the size problem. On the dam side, this can be due to a very small pelvis diameter such as in a heifer, tumors or growths, old trauma, or excessive internal fat. On the calf side, an excessively large calf can be due to a number of congenital, genetic, or nutritional factors. This mismatch represents about 70% of the calving problems. Excessive force or trauma associated with calving can lead to tearing of the cervix, uterus, vagina/perineum, or nerve damage. Some tricks to minimize the chances of damage are: 1. Use plenty of lube and re-apply it often to calf/vagina/ cervical area 2. Arch the back of the calf as it exits the dam. Pull straight out and then towards the heels of the dam. This lifts the pelvis of the calf into the middle of the dam’s pelvis. 3. Rotate the calf to place the long axis of the calf’s pelvis into the longest axis of the dam’s pelvis. 4. Pull one leg of the calf more than the other, to slide one side of the calf’s pelvis into the birth canal before the other. 4 Illustrations from Morrow, Current Therapy in Theriogenology, 1st Edition, p. 254 Other common problems are bent limbs or head and neck bent backwards. It is important to correct any limb or head malpositions before applying traction. In general, it is important to move the limb inward and close to the body and then towards the vagina before applying traction. Sometimes pushing the calf back into the uterus will provide more space to manipulate a limb. Pushing on the shoulder can also be useful if the head is back and can not be reached. This will often bring the head and neck into reach. 5 Common calving presentations. Illustrations from Roberts, Veterinary Obstetrics and Genital Diseases, David and Charles, North Pomfret, Vermont, 1986 p 284 6 Chains or straps that can be sanitized are useful. They should be applied over the pastern and over the fetlock (2 half-hitches). This spreads out the force on the leg over a larger area. Before ever applying any traction or force, it is extremely important that the position of the calf be correct for delivery. Excessive traction on a malpositioned calf will lead to a damaged cow and dead calf. Producers should limit the time that they allow themselves to correct a calf’s position. If the position can not be corrected within 30 minutes then the local veterinary practitioner should be called immediately. Force supplied by two men is sufficient in almost all cases. Calf pullers/calf jacks can be very useful if they are used properly. If force is deemed necessary, it should only be applied after a careful evaluation of the calf and dam have been completed. The producer needs to realize that certain risks are present for the dam, and calves may not survive such a traumatic birth. If necessary the decision to perform a caesarean section should be made quickly while both the health and vitality of the calf and cow are strong. 7 8 Illustrations from Jackson, Handbook of Veterinary Obstetrics, WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1995, pp 46, 47, 49 Packing the vaginal area with ice post calving can help swelling and trauma in the dam. A rectal sleeve is filled with ice, tied with a baler string, and the string tied to the cow’s tail. Ice will very cheaply and effectively reduce the swelling and pain in the perineal area. Medications to limit swelling or to promote the evacuation of the uterus could be prescribed. Sometimes oxytocin is recommended to help contract the uterus. Older cows should again be evaluated for signs that would indicate milk fever. Prompt treatment should be instituted with intravenous or oral calcium. Producers should consult with their private practitioner to develop effective protocols. 9