Salmonella - Home Hygiene & Health

advertisement

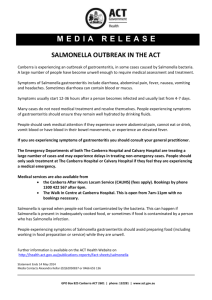

Salmonella: infection and infection prevention through hygiene in the home This leaflet has been put together to provide background information and advice on what to do if there is risk of spread of Salmonella in the home. The target audiences for this briefing material are those in healthcare professions, the media and others who are looking for some background understanding of hygiene issues related to Salmonella and/or those who are responsible for providing guidance to the public on coping with hygiene issues associated with Salmonella. What is Salmonella? Salmonella are a group of bacteria that cause gastroenteritis in humans. There are many different types of salmonella, but Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella enteritidis are the most common types that cause intestinal infection. Salmonellosis occurs year round, but it peaks in the summer and early autumn. The main symptoms of people infected with Salmonella are diarrhoea, fever, and abdominal cramps 12 to 72 hours after infection. The illness usually lasts 4 to 7 days, and most persons recover without the need for treatment. Where is it found? Most types of Salmonella live in the intestinal tracts of wild and domestic animals, birds (especially poultry), reptiles and amphibians (for example terrapins). During slaughtering a high percentage of poultry carcasses become infected from the bacteria in the intestinal tract of infected birds. Salmonella is also found in the gut and faeces of people who have become infected. In some cases people can act as symptomless carriers Most data on GI disease comes from outbreaks reported to national surveillance. The annual Community Summary Report by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), gives an overview of the latest trends and figures on the occurrence of zoonoses and zoonotic agents in humans, animals and foodstuffs in the 27 European Union (EU) Member States and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries.1 Further information on the incidence and prevalence of Salmonella food borne infection can be found European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Annual Epidemiological Report.2 These publications are updated annually. Data for the US is generated through the National Outbreak Reporting System.3 How does Salmonella get into the home? Through infected foodstuffs (most commonly red and white meats, raw eggs, milk, and dairy products) - studies confirm that Salmonella is present in retail poultry in most countries across the world, although the rates of infection (the percentage of samples that are contaminated) vary significantly from one country to another. - the 2010 European Community Summary Report on foodborne infections states that overall, 4.8 % of samples of chicken meat within the EU were positive for Salmonella, although rates from individual countries were mostly between 0.6 and 22%.1 - a UK study showed that Salmonella can sometimes be isolated from the surface of retail poultry packaging. The 2012 European Community Summary Report on foodborne infections reported the domestic kitchen as the origin of 55.6% of Salmonella outbreaks.1 An infected family member or a person who is a Salmonella carrier may act as the primary source of infection in the home. People who are infected can continue to shed the organism in their faeces for a time after recovery. Through domestic pets. Domestic cats and dogs can act as reservoirs of Salmonella. In the United States, it is reported that 10-27% of dogs may carry Salmonella. Infection due to drinking contaminated water can also occur. How do people become infected? Salmonella spreads via the common routes for stomach bugs. It enters the body to infect the gastrointestinal tract via the mouth. It enters the mouth either on food or by contaminated hands (fingers) touching the mouth. Food can be contaminated with Salmonella because it has not been properly cooked or properly stored, or because, after cooking, it has been contaminated from “dirty hands” or contact with contaminated raw food. Hands can be contaminated in a number of ways such as visiting the toilet, handling contaminated food or touching a surface which has been in contact with contaminated food (such as a chopping board) or has been touched by someone else with contaminated hands (tap handles). The hands can also become contaminated by direct contact with animals or their faeces. This means that: 1. Foodborne infection can occur by: Eating undercooked contaminated meat or meat products, poultry or poultry products, eggs and egg products. Eating contaminated or undercooked raw eggs. Direct or indirect cross-contamination from contaminated raw food such as poultry to other raw food such as fruit and salads. - Following preparation of salmonella and campylobacter-contaminated chickens in domestic kitchens, these species were isolated from 17.3% of hands, and hand and food contact surfaces. Isolation rates were highest for hands, chopping boards and cleaning cloths (25, 35 and 60%, respectively, of surfaces sampled). Infected food handlers (who may have no symptoms of illness) can contaminate food during preparation and handling. Page 2/10 Lightly contaminated food can become highly contaminated by the next day if stored with inadequate refrigeration or at room temperature. Salmonella can grow in food and produce large numbers of cells, enough cells for an infective dose when the food is eaten. 2. Person-to-person spread of infection: Person-to-person contact in families, nurseries, and infant schools is an important mode of transmission. Bacteria in diarrhoeal stools of infected individuals can be passed from one person to another if hygiene or handwashing habits are inadequate. This is particularly likely amongst toddlers who are not toilet trained. Family members and playmates of these children are at high risk of becoming infected. Person to person spread from a case via close contact usually occurs during the acute diarrhoeal phase of the illness. Contact with infected animals can also be a source of infection. Salmonella is commonly thought of as a foodborne pathogen, but a study of general outbreaks in England and Wales from 1992 to 1998 indicated that 19% of infections were transmitted by other means including: Person to person spread from a case by close contact Contact with infected animals Environmental contamination. Also: In a USA study of homes in which children under 4 years were known to be infected with Salmonella spp., in one third of homes illness also occurred in other family members at the same time. Environmental sources, infected family members and pets appeared to be more significant risk factors than contaminated foods for development of salmonellosis in these children. In 6% of 200 UK homes, where cases of salmonellosis occurred, Salmonella was isolated from dishcloths. In four out of six homes where there was a Salmonella case, the causative species was isolated from fecal soiling under the flushing rim, and scale material in the toilet bowl, for up to 3 weeks after notification of infection. Further information on the occurrence, survival and transmission of Salmonella in the home can be found in a 2013 IFH report4 Incidence of Salmonella infections Worldwide, bacterial food-borne zoonotic infections are the most commonly reported cause of human intestinal disease, with Salmonella and Campylobacter accounting for over 90% of all reported cases of bacteria-related food poisonings. It is estimated that one third of populations in developed countries are affected by food-borne diseases every year. The 2012 EFSA/ECDC Zoonoses Report1, based on data collected in 2010, estimated that 31.7% of reported food-borne outbreaks occur in private homes. The 2012 European Community Summary Report on foodborne infections cites Campylobacter and Salmonella as the most commonly reported zoonotic diseases.1. In 2010, the number of reported human Salmonella cases continued to decrease. The reduction was 8.8 % (9,598 cases) in 2010, which is about half of the reported reduction rate in 2009 (17.4 % and 22,854 cases). In 2010, 62 deaths due to nontyphoidal salmonellosis were reported (N=46,639). Germany accounted for 51.5 % of Page 3/10 the reduction in the reported number of confirmed cases. Despite decreases in several countries, 16 member states reported more Salmonella cases in 2010 than in 2009. The highest proportional increases in confirmed case numbers, of 24.1 % (760 cases) and 23.3 % (736 cases), were reported by Slovakia and Poland, respectively. Within the five-year period, the greatest average annual decline of 25.0 % in reported cases was observed in the Czech Republic, whereas the highest average annual rise in case numbers, 24.0 %, was observed in Malta. In reality only a small proportion of the total cases (which includes outbreaks and sporadic (individual) infections) gastrointestinal infections are reported to surveillance. An estimate of the true infection rates comes from a UK study of the incidence of GI in the UK in the community which indicates that there are up to 17 million sporadic community cases of infectious intestinal disease annually.5 The data suggest that up to 1 in 4 people in the UK suffer from a GI illness every year. This community-based study, estimated that, for every one reported case of Salmonella, another 4.7 cases occur in the community. CDC estimates that there are 29 infections for every lab-confirmed Salmonella infection. 6 In the USA, a 1999 report on food-related illness estimated that foodborne illness in the USA causes 76 million illnesses each year. Most frequently recorded pathogens were Campylobacter, Salmonella and norovirus, which accounted for 14.2, 9.7 and 66.5%, respectively, of estimated foodborne illnesses.7 A 2011 report (http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/FoodSafety/index.html) released by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that Salmonella infections have not decreased during the past 15 years and have instead increased by 10% in recent years.6 Although foodborne infections have decreased by nearly 25% in the past 15 years, more than one million people in the US become ill from Salmonella each year. Salmonella, is responsible for an estimated $365 million in direct medical costs each year in the US. The 2010 OzFoodNet summarises the incidence of diseases potentially transmitted by food in Australia.8 OzFoodNet reported 30,035 notifications of 9 diseases or conditions that are commonly transmitted by food. The most frequently notified infections were Campylobacter (16,968 notifications) and Salmonella (11,992 notifications). In New Zealand there were 581 reported outbreaks reported during 2011 involving 7796 cases (3237 confirmed and 4559 probable cases). A total of 204 cases required hospitalisation and four cases died. Salmonella spp accounted for 77(1%) of cases and 15 (2.6%) of outbreaks.9 Although Salmonella is commonly thought of as a foodborne pathogen, it is also transmitted from person to person. A study of UK outbreaks suggested that 19% of Salmonella outbreaks are transmitted by non-foodborne routes. The 1999 US report by Mead assessed that, for Salmonella, 5% of reported cases (70,624 of 1,412,498 cases reported annually) were non-foodborne. Further information on the incidence and prevalence of Salmonella food borne infection can be found in a 2009 IFH report10 Page 4/10 Who is at risk? Anyone can be infected by Salmonella. Those most at risk are children and the elderly and other family members with reduced immunity to infection. The European Community Summary Report on foodborne infections estimates that the highest numbers of reported human cases are for age groups 0-4 years and 5-14 years.1 The infectious dose of Salmonella varies depending on the type of Salmonella, the person infected and the nature of the food. For healthy adults the dose may be as high as 1 million cells, but for susceptible children and adults the infectious dose may be as low as 10 cells. Symptoms and complications of disease Young children, the elderly, and those with impaired immune systems are more susceptible than healthy adults, and are the most likely to have severe infections. In these patients, the infection may spread from the intestines to the blood stream, and then to other body sites and can cause death unless the person is treated promptly with antibiotics. In 2010, data from the US suggests that Salmonella caused more than 8,200 infections, nearly 2,300 hospitalisations and 29 deaths (54% of total hospitalisations and 43% of total FoodNet-reported deaths).6 Long term non-gastrointestinal complications may sometimes arise. A small number of people infected with Salmonella will go on to develop pains in their joints, irritation of the eyes, and painful urination. This is called Reiter's syndrome or is sometimes called reactive arthritis. It is quite distinct from rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Reiter’s syndrome typically includes three symptoms: asymmetric arthritis (joints on opposite limbs are affected) in knees and ankles, a non-specific urethritis and conjunctivitis. It can last for months or years, and can lead to chronic arthritis. Although induced by infection, Reiter’s syndrome results from an immunological response and usually develops only in people with a genetic predisposition. Preventing the spread of Salmonella infection in the home In situations where there is risk of spread of Salmonella infection in the home the following hygiene measures should be rigorously implemented. It must be remembered that Salmonella can also be shed by people who have no symptoms – both those who have apparently recovered and those who have not yet developed symptoms. Since the risk of introducing Salmonella into the home, either via people, foods or domestic pets is constant and may not be recognised until an outbreak of infection occurs within the family, this means that good day-to-day hygiene including good food hygiene makes sense General hygiene To prevent transmission of infection from an infected family member (or a family member who may have been exposed to infection outside the home) to other family members or to food: Good hand washing practice is the single most important infection control measure. Hands should be thoroughly washed with soap and running water*. If access to soap and running water is a problem, use an alcohol hand rub or hand Page 5/10 sanitiser. In “high risk” situations where there is an outbreak of Salmonella in the home, it is suggested that handwashing followed by use of an alcohol rub/sanitiser should be encouraged. Hygienically clean surfaces in the bathroom and toilet, with particular attention to washbasins, baths and toilet seat and toilet handles. This can be achieved by cleaning with a detergent cleaner followed by thorough rinsing under running water, or when this is not possible, e.g. for toilet seats, toilet flush handles etc., use a disinfectant cleaner. If someone has diarrhoea, toilets etc should be disinfected after each use. Keep the infected person’s immediate environment hygienically clean. The most important surfaces are those which come into contact with the hands, e.g. door handles, telephones, bedside tables and bed frames. To make these surfaces hygienically clean you need to use a disinfectant product. In a busy household it is not always possible to keep hand contact surfaces hygienically clean at all times. This is why it is so important to wash hands as frequently as possible to break the chain of infection. Cleaning cloths can easily spread Salmonella infection around the home. They should be hygienically cleaned after each use, particularly after use in the immediate area of the infected person or the bathroom and toilet used by that person. This can be done in any of the following ways: - wash in a washing machine at 60ºC using a powder or tablet detergent containing active oxygen bleach (see ingredients on back of pack). - clean with detergent and warm water, rinse and then immerse in disinfectant solution which is effective against Salmonella for at least 20 minutes or as prescribed - clean with detergent and water then immerse in boiling water for 20 minutes. Alternatively use disposable cloths Where floors or other surfaces become contaminated with faeces or vomit, they should be hygienically cleaned at once: - remove as much as possible of the excreta, from the surface using paper or a disposable cloth, then - apply disinfectant cleaner** which is effective against Salmonella to the surface using a fresh cloth or paper towel to remove residual dirt – then - apply disinfectant cleaner** to the surface a second time using a fresh cloth or paper towel to destroy any residual contamination. Disposable gloves should be worn if in contact with faeces, and hands should be washed after removing gloves. Clothing, sheets and pillows and linens from the infected person (or carrier) should be kept separate from the rest of the family laundry and should be laundered in a manner which kills any Salmonella. Either: - for preference, wash at 60C or above, using a powder or tablet detergent containing active oxygen bleach (see ingredients on back of pack). - alternatively wash at 40C with a powder or tablet detergent containing active oxygen bleach (see ingredients on back of pack) Note: washing at 40C without the presence of active oxygen bleach will not destroy bacteria and viruses Do not share towels, facecloths, toothbrushes and other personal hygiene items with the infected or carrier person. Where young children are ill, or at particular risk: - their handwashing, personal and toilet hygiene may need supervision - nappies should be disposed of safely, or cleaned, disinfected and washed. Contrary to popular perception, the faeces of babies can be highly infectious. Page 6/10 Where possible, infected people should stay in their own room and use their own facilities, cutlery, crockery etc. Infected people should particularly avoid contact with those who may be more vulnerable to infection, and their personal items. Food and Kitchen hygiene Rigorous food hygiene is important in preventing the spread of Salmonella in the home. Where there is an infected or suspected infected person in the home, food hygiene practices should focus on preventing contamination of food, particularly ready to eat foods. Where there is a suspected food source of Salmonella in the home, food hygiene practice should focus on containing and destroying the source, and preventing transfer to other foods Infected people should try to stay away from the kitchen and should not prepare food for others. Wash hands after handling food which may be contaminated and disinfect using an alcohol handrub or sanitiser. Wash hands before handling ready to eat foods and disinfect using an alcohol handrub or sanitiser. Hygienically clean all food contact surfaces, utensils and cloths after handling and preparation of raw foods using a disinfectant cleaner which is effective against Salmonella**. Hygienically clean all contact surfaces, utensils and cloths before handling and/or preparing ready to eat foods. Cook foods thoroughly. Wash any foods such as fruit and vegetables to be eaten raw thoroughly under clean running water. Store foods carefully in a refrigerator or freezer. Ensure that raw foods are kept separate from cooked foods. In an outbreak situation where the primary source has not been identified and removed from circulation, avoid or take particular care with known sources such as poultry, cooked meat products, unpasteurised milk and unwashed vegetables. Also: Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and warm water: after contact with pets and other animals after working in the garden *How to wash hands: Handwashing “technique” is very important. Rubbing with soap and water lifts the germs off the hands, but rinsing under running water is also vital, because it is this process which actually removes the germs from the hands. The accepted procedure for handwashing is: Ensure a supply of liquid soap, warm running water, clean hand towel/disposable paper towels and a foot-operated pedal bin. Always wash hands under warm running water. Apply soap. Page 7/10 Rub hands together for 15–30 seconds, paying particular attention to fingertips, thumbs and between the fingers. Rinse well and dry thoroughly. In situations where soap and running water is not available an alcohol- based hand rub or hand sanitiser should be used to achieve hand hygiene: Apply product to the palm of one hand. Rub hands together. Rub the product over all surfaces of hands and fingers until your hands are dry. Note: the volume needed to reduce the number of germs on hands varies by product. In high risk situations where there is an outbreak in the home, handwashing followed use of an alcohol rub/sanitiser should be encouraged. One very simple thing which people can do which can significantly reduce the risk of disease is to avoid putting their fingers to their mouth. **Disinfectants and disinfectant cleaners Make sure you use a disinfectant or disinfectant/cleaner such as a bleach-based product, which is active against Salmonella. For more details on choosing the appropriate disinfectant, see the IFH information sheet “Cleaning and disinfection: Chemical Disinfectants Explained”. .Consult the manufacturers’ instructions for information on the “spectrum of action”, and method of use (dilution, contact time etc). For bleach (hypochlorite) products, use a solution of bleach, diluted to 0.5% w/v or 5000ppm available chlorine. Household bleach (both thick and thin bleach) for domestic use typically contains 4.5 to 5.0% w/v (45,000-50,000 ppm) available chlorine. In situations where “concentrated bleach” is recommended a solution containing not less than 4.5% w/v available chlorine should be used. Bleach/cleaner formulations (e.g. sprays) are formulated to be used “neat” (i.e. without dilution). It is always advisable however to check the label as concentrations and directions for use can vary from one formulation to another. Other “facts about” sheets giving information on Salmonella UK National Electronic Library on Infections (NELI) Salmonella enteritidis. http://www.neli.org.uk/IntegratedCRD.nsf/NeLI_Organisms1?OpenForm&Seq=1#_ RefreshKW_Bacteria Public Health England: Salmonella. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/salmonella/gen_inf.htm. US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/DiseasesConditions/. European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention: Salmonellosishttp://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/salmonellosis/Pages/ind ex.aspx Page 8/10 IFH Guidelines and Training Resources on Home Hygiene Guidelines for prevention of infection and cross infection the domestic environment. International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. Available from: http://www.ifh-homehygiene.com/best-practice-care-guideline/guidelinesprevention-infection-and-cross-infection-domestic Guidelines for prevention of infection and cross infection the domestic environment: focus on issues in developing countries. International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. Available from: http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/bestpractice-care-guideline/guidelines-prevention-infection-and-cross-infectiondomestic-0 Recommendations for suitable procedure for use in the domestic environment (2001). International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. http://www.ifhhomehygiene.org/best-practice-care-guideline/recommendations-suitableprocedure-use-domestic-environment-2001 Home hygiene - prevention of infection at home: a training resource for carers and their trainers. (2003) International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. Available from: http://www.ifh-homehygiene.com/best-practice-training/home-hygiene%E2%80%93-prevention-infection-home-training-resource-carers-and-their Home Hygiene in Developing Countries: Prevention of Infection in the Home and Peridomestic Setting. A training resource for teachers and community health professionals in developing countries. International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. Available from: www.ifh-homehygiene.org/best-practice-training/homehygiene-developing-countries-prevention-infection-home-and-peri-domestic. (Also available in Russian, Urdu and Bengali) References 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The European Union Summary Report on Trends and Sources of Zoonoses, Zoonotic Agents and Food-borne Outbreaks in 2010. Scientific report of EFSA and ECDC Downloadable from http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/doc/2597.pdf European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Annual Epidemiological Report 2013. http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/annual-epidemiologicalreport-2013.pdf Hall AJ, Wikswo ME, Manikonda K, Roberts VA, Yoder JS, Gould LH. Acute gastroenteritis surveillance through the National Outbreak Reporting System, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1908.130482 . Bloomfield SF. Exner M, Signorelli C, Nath KJ, Scott EA. 2012. The chain of infection transmission in the home and everyday life settings, and the role of hygiene in reducing the risk of infection. http://www.ifh-homehygiene.com/best-practice-review/chain-infectiontransmission-home-and-everyday-life-settings-and-role-hygiene The Longitudinal study of infectious intestinal disease in the UK (IID2 study): incidence in the community and presenting to general practice Tam CC, Rodrigues LC, Viviani L, et al. Gut (2011). doi:10.1136/gut.2011.238386. Vital signs – making food safe to eat 2011. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2011-06-vitalsigns.pdf. Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, et al. Foodrelated illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 1999;5:607-25. Monitoring the incidence and causes of diseases potentially transmitted by food in Page 9/10 9 10 Australia: annual report of the ozfoodnet network, 2010. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/cda-cdi3603-pdfcnt.htm/$file/cdi3603a.pdf Summary of Outbreaks in New Zealand 2011. Institute of Environmental Science and Research Limited. July 2012. https://surv.esr.cri.nz/PDF_surveillance/AnnualRpt/AnnualOutbreak/2011/2011Out breakRpt.pdf Bloomfield SF, Exner M, Fara GM, Nath KJ, Scott, EA; Van der Voorden C. The global burden of hygiene-related diseases in relation to the home and community. (2009) International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene. http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/review/global-burden-hygiene-related-diseasesrelation-home-and-community. Page 10/10