Genealogy Resources

advertisement

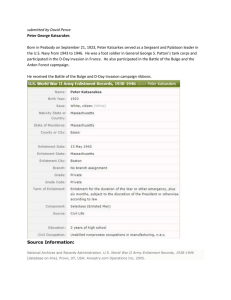

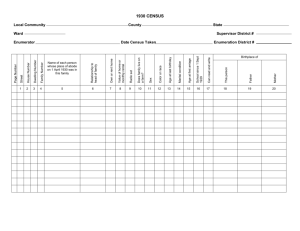

Genealogy Tech Talk Lora Cokolat, Electronic Resources Librarian lora.cokolat@library.sccgov.org 408-293-2326 x 3017 (Adapted from Jack Simpson, Genealogy 101, RUSA Online Professional Development) Basic Research Strategy: START WITH YOURSELF AND MOVE BACKWARDS. 1. 2. 3. 4. Get Organized (fill out a pedigree chart) Talk to Ancestors Research in the U.S. Census Research in Vital Records Census Basics: The census has been taken every 10 years since 1790. A count of the population is required by the Constitution, because the appointment of House of Representatives is based on population. Every 10 years, census takers were sent out. They were assigned a district, (called an enumeration district, or E.D.) and went door-to-door recording information about the residents on a form called the population schedule. Once the population schedules were filled out, they were sent to Washington, where they were used to compile statistics. Once the counting was done, the Census Bureau issued a statistical report. The statistical report was usually published within several years of the census. In contrast, the population schedules are closed for 72 years, for privacy reasons. In casual use, researchers call both the population schedule and the statistical report “the census.” But they are two very different things. The population schedules contain personal names in information about individuals. Statistical reports exclude personal names, but instead record demographic information. 1790-1840: Census only recorded the head of the household. 1850: First census to name all the members of the household. 1850-1860: Separate slave schedules counted the number of slaves and the owner’s name, but did not give the names of slaves. 1880: First census to record the address being enumerated. 1900: First census to ask immigrants the year of immigration and naturalization status. 1930: Currently the most recent population schedule available. 1 For genealogical purposes, schedules from 1850 and later are far more useful from the earlier schedules. Because they name children as well as their parents, it is possible to use later schedules to connect generations. http://www.censusfinder.com/ lists the questions for the 1790-1930 schedules, and http://usa.ipums.org/usa/voliii/tEnumForm.shtml also lists the census questions from 1850present. Exercise 1: What can we learn by reading a census page? A word of caution: Census research is not always straightforward. 1. The census misrecords a name, or there is name variation. 2. The census indexer misreads a name 3. The family story is wrong Vital Records: Birth, marriage and death records. Access to vital records varies widely by locality, for two reasons: 1. Localities kept different kinds of records over the years. 2. Localities have different rules for access today. There are several reference books that describe record holdings at the local level. Two popular directories of local records are The Handybook for Genealogists published by Everton, and the Ancestry Red Book. Internet: USGenWeb pages vary greatly depending on who is maintaining. Researchers can also visit the webpage of a particular county government. Some county government pages have very clear information about obtaining vital records, while others don’t. Also, see this webpage from the Center for Disease Control – Where to Write for Vital Records: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/w2w.htm Indexes for Vital Records Research: Internet: http://www.cyndislist.com/usvital.htm, State Government webpages, USGenWeb, Family History Library Catalog “place search”, Genealogy Roots Blog at http://genrootsblog.blogspot.com/ Subscription Databases: Ancestry.com and World Vital Records 2 Print: (county, state) – genealogy, marriage records (state, county), registers of birth, etc (state, county). Death records usually record: The localities where the deceased was born Names of the parents of the deceased The name of a spouse or next-of-kin The individual’s most recent address The individual’s occupation The date of death The cause of death Place of burial Marriage records typically record: Name of groom Maiden name of the bride Date of marriage Official who performed the ceremony Age of the bride and groom Parents of the bride and groom Birth records tend to record: Place of birth Date of birth Gender and race of child Name of Father Maiden Name of Mother The Social Security Death Index (SSDI) It covers the period from the mid-1960s to the present, and includes the vast majority of Americans who died during that period. The index entry typically tells you the last residence of the individual, the date (or at least the month) of death, the sate where the individual originally applied for Social Security, and the individual’s date of birth. It isn’t a great amount of information, but it can be helpful for a beginner. It might lead us to an obituary, or to search the census. More importantly, researchers who find an individual in the SSDI can write to the Social Security Administration and request a copy of the individual’s original application. It would have been created when an individual began working and generally records: Full name 3 Full name at birth (including maiden name) Present mailing address Age at last birthday Date of birth Place of birth (city, county, state) Father’s full name “regardless of whether living or dead” Mother’s full name, including maiden name, “regardless of whether living or dead” Sex and race Ever applied for SS number/Railroad Retirement before? Yes/No Current employer’s name and address Date signed Applicant’s signature Copies of the application cost $27. Ancestry’s SSDI database will automatically generate the letter to send to the Social Security Administration. Exercise 2: How can we request a copy of an original Social Security application using Ancestry.com? Newspapers and Obituaries: Local Public Libraries Many libraries provide obituary lookups as service, and some have created indexes to local obituaries. Statewide repositories Many states have a statewide historical library or archive, and these kinds of institutions often collect historical newspapers. Major Commercial Digitization Projects A number of major newspapers have digitized their old issues, mostly in collaboration with ProQuest. These include the New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, the Atlanta Constitution, etc. ProQuest has a product called ProQuest Obituaries that extracts just the obituary from these papers. (Not Available at SCCL) Genealogy Bank Newsbank also offers access to digitized historical newspapers. It contains many smaller newspapers such as the San Jose Mercury News. Ancestry.com Ancestry’s home subscription also offers a number of digitized newspapers. 4 Newspaper Archive Pay By Subscription database. Makes available historical newspapers from the United States and the world. Free Digitized Newspapers The Library of Congress has started a major newspaper digitization project, Chronicling America at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/. While it doesn’t contain a huge amount of material now, it seems like a platform for large-scale digitization. City Directories: City Directories are the predecessor to today’s phone books. The bulk of them were published in the period 1860-1930. They listed city residents (Name, Home address, Job title, Place of employment) and city institutions. City directories are great tools for genealogists for two reasons. 1. They track individuals in the years between censuses. 2. They provide an annual snapshot of a city: its churches, schools, street addresses and other basic information that researches find useful. There are a number of places that tend to hold city directories in print e.g. your local public library. Digitized city directories are available from a number of websites. Ancestry.com offers some digitized directories. USGenWeb might also have some. Increasingly, book digitization projects such as Google Books at http://books.google.com/ and the Open Content Alliance/Internet Archive at http://www.archive.org/ include digitized copies of city directories. Local Histories and Family Histories: Novice genealogists often overlook local histories, because they assume that their ancestors would not merit mention in a history. This is a misperception, as local histories often describe even the most mundane lives of local residents. This is particularly true of the subscription-based county histories published in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. At that time, most Americans did not have access to bookstores. Instead, salesman would sell a forthcoming book door-to-doors to subscribers before the book was printed. Local histories were a popular genre for subscription-based publishers. Canvassers would gather historical information about the county while simultaneously selling the publication. As a result, these books are packed with detail about local residents. County histories typically record the history of each town and township in a county, describe the founding of institutions such as churches and schools, and contain biographical sketches of county residents. 5 Researchers can find local histories in a number of ways. To locate a print history of a county, researchers can search WorldCat for the subject headings: (name) county, (state) – history (name) county, (state) – biography Family Histories Most family histories were self-published in small runs and are fairly rare. The bulk of family histories published in the United States describes early Anglo-American families, because these families were the most popular subject for genealogical publishing before the 1970s. In the 1970s, the genealogical field broadened, and a more diverse group of Americans published their family history. The LC subject heading for family histories is: (Surname) family For Example: McCarty family Besides WorldCat, researchers should check the Family History Library catalog at http://www.lib.byu.edu/fhc/index.php, using the “surname search” option. Other places to check are HeritageQuest, Ancestry.com, Google Books, and the Internet Archive. Beyond this, there are also family web sites that provide the same function as published family histories. The “Surname, Family Associations and Family Newsletters” section of Cindy’s List at http://www.cyndislist.com/surnames.htm is a good directory to such sites. Exercise 3: Locate a family history using Heritage Quest and Ancestry.com. Cemetery Records: Generally, civil death records give the place of burial. Obituaries also sometimes will list a place of burial. If these sources do not exist, or do not record the place of burial, researchers can search for cemetery indexes. Many cemetery records have been indexed by local genealogical societies and published as books or placed on the Internet. Researchers can search for published cemetery indexes by searching WorldCat. Most indexes will be cataloged under the heading: County, state- genealogy One helpful database is FindaGrave.com, a free commercial site. The site started as a hobbyist site for researching the graves of famous people, but now contains a considerable amount of information about cemeteries. 6 Once a researcher has identified a potential cemetery, he or she can contact the cemetery and request information about a burial, or they can visit the cemetery. Military Records: Many ancestors of modern-day Americans were not involved in the American Revolution. In other words, the bulk of immigration to the U.S. occurred after the Revolutionary period, so a low percentage of American ancestors were in North America in 1776. But even though Revolutionary records cover a small group in comparison to later conflicts (especially the Civil War), participation in the Revolution is a popular topic for genealogical inquiry. Three sets of records are good starting points for researching soldiers in the Revolution: military service records, pension records and bounty land records. Service records include some basic information about each solider, including the unit they served in, their birthplace and date, the rank they achieved, and the dates of service. Footnote.com has digitized the original service records from the National Archives. If a researcher doesn’t have access to Footnote, they can check the index to the records and then request copies of the original from the National Archives. An index to these records was microfilmed by the National Archives, and the National History Publishing published a print index by Virgil White in 1995. After the Revolution, some veterans received a pension, while others chose to be paid for their service with bounty land. Both HeriteQuest and Footnote.com have digitized the full set of pension records. The pension and bounty land records are also indexed by microfilms M805 and M804 from the National Archives and by a print index by Virgil White. If researchers don’t have access to Footnote, they can request copies of the full pension or bounty record using NARA’s online request form, or by mailing NATF form 85 to the Archives (The Archives will mail researchers a form if requested). For more information, refer to this link: http://www.archives.gov/contact/inquire-form.html. Civil War Military Records One basic starting source for Civil War genealogical research is the Civil War Soldier and Sailor System (CWSSS), an online database maintained by the National Park Service: http://www.itd.nps.gov/cwss/ The CWSSS compiles rosters of both Union and Confederate sources. It indicates which unit the soldier served in, which is a basic piece of information for further research. The U.S. Government created two sets of records on soldiers of great genealogical interest: military service records and pension records. 7 Military service records document what soldiers did during the war- the battles they fought in, the rank they achieved, injuries sustained and other details of their service. Once you have determined what unit a soldier served in, you can request the military service record from the National Archives in Washington D.C. Researchers can request copies using NARA’s online request form or by mailing NATF 86 to the Archies (the Archives will mail researchers a form if requested). For more information visit: http://www.archives.gov/contact/inquire-form.html For genealogy research a soldier’s pension file is often more useful than his service record. The pension file is an unusually valuable genealogy record because it traces a veteran and his widow forward from the 1860s for the rest of their lives – documenting when they move, their marriages, medical information, and death information. The National Archives has a microfilmed index to the pension files: Microfilm T288, General Index to Pension Files. The index is also available at Ancestry.com. The index is searchable by the name of a veteran, or the name of his spouse. Once a researcher obtains an entry from the index, they can obtain the pension file from the National Archives in Washington D.C. The current cost is $125 for a complete file. After the Civil War, the official service records of the Confederate Army were preserved and are now held by the National Archives. The process of searching for these records is similar to that of Union soldiers. Certain states also kept service records of soldiers from the war – the respective state archives of the former confederate states are the best place to research these records. Confederate soldiers did not receive Federal pensions, but some states did issue pensions. 1890 Veteran’s Schedule of the Census In 1890, the U.S. Census included a special schedule for veterans and their windows. While most of the 1890 census was destroyed in a fire, the Veteran’s Schedule remains for the following states: Kentucky (part), Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma and Indian Territories, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. The schedule records basic information about the veteran’s service, including the unit they served in. Ancestry.com has digitized the entire remaining set. Regimental Histories Many Civil War unites have been described in unit histories. The best bibliography of regimental histories is Charles E. Dornbusch’s Regimental Publications and Personal narratives of the Civil War (New York Public Library, 1961 – 1987.) Researchers will also find brief unit histories for Union regiments in Frederick Dyer’s A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, originally published in 1908. Dyer’s histories are also available online at: http://www.civilwararchive.com/ 8 Military Records for later Conflicts Military records for later conflicts are harder to research: A major fire in a National Archives repository destroyed 80% of the Army service records for soldiers discharged between 1912 and 1960. Privacy concerns limit access to records of recent conflicts Draft records from the WW I were microfilmed by the National Archives and are now available on Ancestry.com. The National Archives recently released a database of World War II Enlistment Records, available as part of the Access to Archival Database (ADD) system: http://aad.archives.gov/aad The website of the National Archives provides good information about the research process: http://www.archives.gov/genealogy/military There are also several good books on 20th Century military research. How to Locate Anyone Who Is Or has Been in the Military by Richard S. Johnson and Debra Knox (Spartanburg, SC: MIE Publishing, 1999) James Neagle’s U.S. Military Records: A Guide to Federal and State Sources, Colonial America to the Present. (Salt Lake City, UT: Ancestry) Church Records: The first step in locating church records is to determine what congregation an ancestor attended. For example, civil marriage records or an obituary may provide some clues. The Family History Library catalog at http://www.familysearch.org/eng/Library/FHLC/frameset_fhlc.asp is a good starting point, as it has the world’s largest collection of church records. To browse church records for a certain locality, choose the “place” search and then select the “church records” heading. The keyword search option is also useful if you know the name of the congregation. Another option is to search for a local religious archive that might collect church records. For example, many Roman Catholic archdioceses maintain archives that collect records. There are also nationwide archives for particular denominations. There is a good rundown of such repositories in chapter six of the current edition of The Source by Szucs and Luebking. Immigration Research: There are two basic kinds of records that record immigration: passenger records and naturalization records. In the years 1900-1930 the census asked immigrants the year that they arrived in the United States and their naturalization status. The answers to these questions help researches narrow their 9 search. The town of origin for a person is sometimes recorded on death records or in an obituary, so these sources are also worth exploring before searching for immigration documents. Passenger Records: Passenger lists record the passengers on board of a particular ocean-crossing vessel. These lists are also referred to as manifests. Researchers will find that the passenger arrival records for New Orleans are different than those for New York, and records from the 1860s are unlike those from the 1920s. Colonial era to 1820: In these early period of immigration, passenger lists were fairly spare- they did not record a great deal of information about the immigrants. Many of the manifests from this era have been lost or destroyed. Researching during this time period is hit-or-miss. But because this era has been thoroughly researched by generations of genealogists, what information exists has been fairly well transcribed and indexed. 1820-1880: More manifests exist from this time period, and many were preserved and microfilmed by the National Archives. The records tend to be somewhat sparse in the information they provide, usually listing the passenger, name, age, and country of origin. Many of these records were indexed in print publications and microfilm or are available digitally through Ancestry.com and other websites. 1880-1957: For this period, detailed manifests exist for most U.S. ports. Many of the records are available digitally through commercial and free websites. Passenger lists in this period became increasingly detailed, often listing the passenger’s birthplace, final U.S. destination and sometimes the address of an American relative. For the post-1820 era, researchers can see the original passenger lists on microfilm. The National Archives’ website at http://www.archives.gov/genealogy/immigration/passenger-arrival.html lists what records are available on microfilm. These are the original lists of passenger arrival, organized by port, date, and ship. Researches can use these microfilm at branches of the National Archives or can borrow them through the Family History Library. The original lists are organized by date, and are often difficult to read, so researchers are better off starting with a passenger list index, when possible. Passenger List Indexes: Passenger and Immigration Lists Index (Filby and Meyer) - Extracts passenger information from passenger lists transcribed in secondary books or journals. This index is available on Ancestry.com Ethnic Passenger Lists - Germans to America (Ira Glazier, ed) - Italians to America 10 - Migration from the Russian Empire The Famine Immigrants Castle Garden and Ellis Island Databases Castle Garden and Ellis Island were arrival stations for international passengers traveling to New York City. Castle Garden was active from 1855 to 1890, and Ellis Island served from 1892 to 1954. - Ellis Island Database: http://www.ellisisland.org/ Castle Garden Database: http://www.castlegarden.org/ The genealogist Stephen P. Morse has created tools for navigating the Ellis Island database more easily. A more user-friendly search interface that Morse created allows users to devise more complex searches. By truncating names, or searching fields such as age at arrival, year of arrival, and country of origin, users can overcome name variations. Morse also created a tool to browse the Ellis Island manifest images by date of arrival, which allows users to locate passenger manifests that are incorrectly linked. - http://www.jewishgen.org/databases/eidb/ellisgold.html? - http://stevemorse.org Passenger Records on Ancestry.com Ancestry has been aggressively digitizing the microfilmed passenger lists from the National Archives, covering the period of 1820-1957. These records are similar to those included in the Ellis Island database, but also cover other ports such as New Orleans, Boston, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. Exercise 4: What can we learn by reading a passenger record? On the Horizon: FHL Indexing Currently, the Family History Library is engaged in a major digitization/indexing effort that may make more of these records available online. See this link for more information: http://pilot.familysearch.org/recordsearch/start.html#start Naturalization Records: Naturalization is the legal process whereby immigrants become citizens. The naturalization process changed over time in the U.S. Colonial Period: Naturalization was uncommon in this period. British subjects did not need to naturalize when coming to the American colonies. Some non-British immigrants did take an oath of allegiance to the British crown, and scattered records of those oaths exist. 11 1790-1906: During this period, naturalization records were filed at a local court. Naturalization documents typically recorded the applicant’s name, date of birth, port of entry and date of entry, but vary depending on the court. Some courts recorded more information, such as the applicant’s place of birth. Women automatically assumed their husband’s naturalization status during this period, so few women are well documented in the naturalization records of this era. 1906-1922: In 1906, the Federal government standardized the naturalization process under a new administrative body, the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization. Naturalization records from this period contain a great deal of information, including place of birth, date of birth, port and date of entry, name of ship, and names of spouses and children. 1922-2002: In 1922, Congress passed a law ending the automatic naturalization of women married to naturalized citizens. This motivated more immigrant women to naturalize than in previous years. Otherwise, the naturalization process remained largely the same until 2002, when immigration and naturalization was placed under the authority of the Department of Homeland Security. - Christina Schaefer’s Guide to Naturalization Records of the United States is an essential reference work for locating where the records of a particular county or state are held. Another option for researchers is to search for ancestors in foreign records prior to immigration. For example, if an ancestor immigrated from England in 1885, researchers can search for them in the 1881 British Census. This kind of research is beyond the scope of this workshop, but here are some good online resources to check out: - Ancestry.com (Offers some foreign Census records, Address Books, Discussion Boards, etc.) - Family History Library (Do a Place Name search to see what’s available on microfilm) - JewishGen (Great place for Jewish ancestry research worldwide) - The Central Database of Shoah Victims' Names – Yad Vashem (Find Holocaust records) - WorldCat (Search for print material such as census, burials, etc. for ILL) - ShtetlSeeker database from JewishGen (a geographic tool to search current and historical places in Europe, North Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East.) - The Internet (Perform a keyword search using your favorite search engine) 12