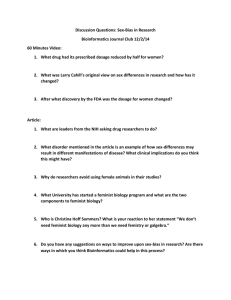

Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science First published

advertisement