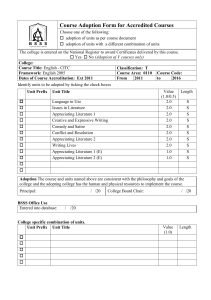

PLANGE v. PLANGE [1977] 1 GLR 312

advertisement

![PLANGE v. PLANGE [1977] 1 GLR 312](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007747243_2-e689454aa600b109cd58e342be2a5f5a-768x994.png)

PLANGE v. PLANGE [1977] 1 GLR 312-323 COURT OF APPEAL, ACCRA 21 JULY 1976 SOWAH, ANIN AND FRANCOIS JJ.A. Adoption—Customary adoption—Essential requirements—Consent of child's parents and expression of adopter's intention before witnesses—Consent to be objectively inferred from express words or conduct of child's parents—Legal effect of customary adoption. HEADNOTES The plaintiff and her deceased husband were first married under customary law and later under the Marriage Ordinance, Cap. 127 (1951 Rev.). The marriage was not blessed with any children. The couple therefore decided to adopt the plaintiff's infant niece, A., then aged four. The consent of A.'s natural father to the proposed adoption was duly obtained. After the couple had collected A. from her mother at Keta, a ceremony of adoption was performed in the presence of A.'s natural father, the plaintiff's aunt and the plaintiff and the deceased husband. After the pouring of libation, A. was renamed after the deceased husband and A.'s natural father handed her to the deceased husband. After being adopted, A. stayed with the plaintiff and her husband until the husband sent her to a boarding school. The husband was solely responsible for paying the school fees of A. who grew up to know the deceased husband and the plaintiff as her father and mother respectively. On the death intestate of the husband, the plaintiff applied in the High Court for a declaration that, she and the deceased husband, had validly adopted A. under customary law as their daughter and that under the Marriage Ordinance, Cap. 127 she and A. had a major interest in the estate and she was therefore the proper person to be granted letters of administration to administer the estate. The defendant, the brother of the deceased husband, and the co-defendant, the sister, caveated. The defendant denied knowledge of A.'s adoption by his deceased brother but he admitted having "seen" A. with his brother for fifteen years or more. There was also evidence that, some years after the adoption, the deceased in a reply to a question by his sister, the codefendant, said that A. was his daughter and that he had adopted her. In his judgment (High Court, Accra, 23 February 1968, unreported; digested in (1968) C.C. 88) the trial judge held that on the facts, there had not been a valid customary adoption of A. because, inter alia, a valid customary adoption could only be performed "by the head of the family with the consent and concurrence of the principal members of the family and at a joint meeting of the two transacting families." He therefore held that A. was not an issue of the marriage under the Ordinance and that the plaintiff had only a one-third interest in the estate. On appeal by the plaintiff, Held, allowing the appeal: (1) the essential requirements for a valid customary adoption, were the expression of the adopter's intention to adopt the infant before witnesses and the consent of the child's natural parents and family to the proposed adoption - such consent to be objectively [p.313] ascertained or inferred from either their express words or conduct. Consequently, the consent of the adopter's own family and the previous joint meeting of the families of the child and the adopter were unnecessary. On the facts of the case, there was a valid customary adoption of A. and the trial judge had erred in holding otherwise. Tanor v. Akosua Koko [1974] 1 G.L.R. 451, C.A. followed. (2) The legal effect of customary adoption was (a) the adopted child acquired the status of a child of the marriage and enjoyed the same bundle of rights (including rights of inheritance), duties, privileges and obligations as the natural child and (b) the rights and liabilities of the natural parents of the adoptee became permanently extinguished and devolved on the adopting parents. Decision of Ollennu J.A. (sitting as an additional judge of the High Court) in Plange v. Plange, High Court, Accra, 23 February 1968, unreported; digested in (1968) C.C. 88 reversed. CASES REFERRED TO (1) Tanor v. Koko Akosua [1974] 1 G.L.R. 451, C.A. (2) Coleman v. Shang [1961] G.L.R. 145; [1961] A.C. 481; [1961] 2 W.L.R. 562; [1961] 2 All E.R. 406; 105 S.J. 253, P.C.; affirming [1959] G.L.R. 390, C.A. NATURE OF PROCEEDINGS APPEAL against a decision of Ollennu J.A. (sitting as an additional judge of the High Court, Accra) wherein he held, inter alia, that the plaintiff 's infant niece had not been adopted in accordance with customary law and did not therefore qualify as an issue of the plaintiff's marriage under the Marriage Ordinance, Cap. 127 (1951 Rev.). The facts are sufficiently stated in the judgment of Anin J.A. COUNSEL J. K. Agyemang for the appellant. Lokko for the respondents. JUDGMENT BY ANIN J. A. Bart Kojo Plange died intestate on 16 May 1964 at Accra, leaving behind a widow (the plaintiff-appellant herein) whom he married firstly under customary law in 1949 and subsequently under the Marriage Ordinance, Cap. 127 (1951 Rev.), on 4 December 1954. Upon his death, the plaintiff applied to the court below for letters of administration to administer his estate. The defendant, a brother of the whole blood to the deceased, entered a caveat to the plaintiff's application and filed his affidavit of interest. As the parties could not agree on the proper person to whom letters of administration should be granted, the plaintiff, pursuant to the court's order made under Order 60, r. 21 (2) of the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, 1954 (L.N. 140A), instituted this action. The codefendant (a full sister of the deceased) was later joined upon her own application. In her statement of claim, the plaintiff disclosed that prior to their wedding in 1954 she and her husband adopted a girl called Alice and the [p.314] deceased treated her in all official documents as his daughter. She further pleaded that "by virtue of the said adoption and other declaration of the deceased, the defendant together with other members of the family are estopped from denying that the said Alice was the adopted and lawful daughter of the deceased." The plaintiff's case was simply that since there was a valid adoption under the customary law of Alice, she and Alice have the major interest in her late husband's estate; and she is the proper person to be granted letters of administration to administer the estate. The defendant denied the allegation of adoption and maintained that Alice is the niece of the plaintiff and remained in her care and control; that she was neither adopted by Bart Kojo Plange (deceased) nor treated by him as his daughter in official documents. There was also a disagreement between the parties in their pleadings about the various properties which Bart Kojo Plange died possessed of; but the question what properties belonged to the deceased and the plaintiff separately or jointly was expressly excluded by the trial judge from trial on the ground that it raised title and possession of land, which had not been claimed. The only issues for trial were therefore (a) whether or not Alice was adopted by the deceased and the plaintiff as their daughter; and (b) who was the proper person entitled to the grant of letters of administration? Consequently, whether a portion of the estate of the deceased was ancestral family property or not, was not an issue before either the trial court or this court. In evidence, the plaintiff disclosed that as her marriage with the late Bart Kojo Plange was not blessed with any issue, she and her husband decided to adopt her infant niece, a girl of four, called Mary Anthonell Robinson. They duly obtained the girl's natural father's consent to the proposed adoption and collected the girl from her mother at Keta. The ceremony of adoption was performed in Accra. Those present included the girl's natural father, a Mr. Robinson, Mrs. Akrobetu (the plaintiff's aunt), her late husband and herself. After the pouring of libation, the child was renamed Alice Aku Plange; and her natural father handed her to the plaintiff's husband, who in turn handed her to the plaintiff. After being adopted, Alice stayed with the couple until the husband sent her to the Ola Convent at Asikuma. He was solely responsible for paying her school fees throughout her stay at the convent. The plaintiff further stated that the defendants knew all along that Alice had been adopted by her and her husband; but they raised no protest. They were therefore now estopped by their conduct from challenging Alice's adoption. To illustrate her point, she gave a graphic description of an incident in 1963 when the co-defendant paid them a visit. On seeing a box bearing the inscription "Alice Bart Plange," the co-defendant asked her late brother to whom the box belonged. To her question, the plaintiff's late husband replied: "My daughter Alice; I have adopted her." The plaintiff's witness, Mrs. Flora Akrobetu, generally confirmed her account of the adoption ceremony of Alice. When first she was asked if she [p.315] approved of their proposal to adopt Alice, she had replied: "My niece I like it." She revealed further that she once accompanied the couple as they took Alice to the convent at Asikuma. Alice herself gave evidence and she was not challenged by cross-examination. Giving her full name as "Alice Bart Plange," she stated as follows: "I am a student in Ola Training College and I live at Accra. I know the plaintiff. I know her as my mother. I grew up to know her as my mother and the late Kojo Bart Plange as my father. It was my said father who sent me to Asikuma Convent. Up to today I stay with Mrs. Plange, the plaintiff." The defendant's evidence was as brief as Alice's. On the adoption issue, he stated: "I know Alice, witness for the plaintiff. She is the niece to the plaintiff. Her father was a half-brother to the plaintiff. I do not know anything about the adoption which the plaintiff alleges." Under cross-examination, he denied any knowledge of his late brother's alleged adoption of Alice; or of her surname being Bart-Plange. However, he admitted having "seen" Alice with his brother for "fifteen years or more." For her part, the codefendant offered no evidence. In his judgment delivered on 23 February 1968, unreported, digested in (1968) C.C. 88 the learned judge (Ollennu J.A. sitting as an additional judge of the High Court, Accra) held, inter alia that: "Adoption under customary law is analogous to alienation of family property, or severance of family ties, a very rare custom known by different names in different tribes, e.g., in Akan it is known as cutting ekar or kahirie among the Ga it is known as tako mlifoo, and among the Ewe as taku mama. As to severance of family ties see Amoabimaa v. Badu (1956) 1 W.A.L.R. 227, W.A.C.A., Okaikor v. Opare (1956) 1 W.A.L.R. 275 and Fynn v. Kuma (1957) 2 W.A.L.R. 289. On the principle that one single member of a family is incompetent on his own, i.e. without the consent and concurrence of the head and principal members of the family to make valid alienation of family property, on the same principle, one parent who, after all is himself a species of property of his family, is incompetent to alineate his child, another of the family properties. Therefore a valid adoption under customary law is such a serious operation that it can only be performed by the head of the family with the consent and concurrence of the principal members of the family, and at a joint meeting of the two transacting families; and must be celebrated with certain formalities, rites and customary performance, including the ceremony of naming the child, giving it a family name. The particular rites and ceremonies may differ from tribe to tribe, but in each one the fundamental concept of uprooting from one family and transplanting into a new family must be symbolically demonstrated." Earlier on in his judgment he said: [p.316] "Adoption purports to effect a transplantation of a person from each of the two natural families into which he is born, into two other families, thereby depriving the one group of families of their rights, interests and obligation in the person adopted, and conferring those rights and interests, and imposing those obligations and privileges upon the other group of families. Therefore where a person already belongs to a family there is no necessity for a member of the family to adopt him. The member of the family has a right and obligation to look after him without any forms and ceremonies." Turning to the facts of the case, the learned judge observed that "the child was the niece of the plaintiff. She and her late husband had been caring for her as a foster-child as by custom any member of the family may do for a child. Such an act cannot give rise to adoption." He further held that the plaintiff failed to prove an adoption complying with his above-stated conditions. There was therefore no issue of the marriage under the Marriage Ordinance, Cap 127, s. 48, and the plaintiff's interest in the deceased's estate was limited to one-third. In this appeal learned counsel for the plaintiff argued two grounds together: (a) that the learned judge erred in holding that the plaintiff failed to prove that the child was adopted according to custom; and (b) that there was sufficient evidence led to show that the child, even if stated to be related to the plaintiff, was in fact adopted and cared for or maintained by the deceased as his "daughter" and assisted by the plaintiff. He first submitted that Ollennu J.A.'s formulation of the customary law of adoption was, with respect, erroneous, or at any rate too strict and not justified by any known authority. He invited us to hold on the evidence that a valid customary adoption was proved; and he relied heavily on this court's recent decision in Tanor v. Akosua Koko [1974] 1 G.L.R. 451, C.A. In that case, the plaintiff, a Krobo, claimed to have been adopted by one Dobre, an Akan from Akim Abuakwa, and assimilated into his family. Upon the demise in turn of Dobre, his two nephews and niece, the plaintiff claimed to be entitled to succeed to Dobre's niece, since she was the last surviving relation in the maternal line. On the other hand, the defendants asserted that the plaintiff was only a divorced wife of Dobre; and that being a total stranger to the late Dobre and to his deceased niece, she had no claim to her inheritance. The learned trial judge found as a fact that the plaintiff was customarily adopted into the family of Dobre, and that by virtue of her adoption, she was entitled to succeed to Dobre's niece. In affirming the learned trial judge's findings and dismissing the defendants' appeal, this court examined the customary law of adoption; in particular, the formulation of the law by Ollennu J.A. sitting in the court below as an additional judge in the instant case of Plange v. Plange. Apaloo J.A. (with whose leading judgment Lassey J.A. concurred) held - doubting the correctness of Ollennu J.A.'s statement of the law in the instant case - that the essential requirements for the adoption of an infant into a family in accordance with customary law were the consent [p.317] of the child's parents and family and the expression of the adopter's intention to adopt the infant before witnesses. There was evidence on record that Dobre obtained the consent of the plaintiff's parents and family to adopt her, and that he clearly stated his desire and intention to adopt her before witnesses. While treating the learned trial judge's formulation of the customary law with great deference, Apaloo J.A., nevertheless, held that the essential requirements for customary adoption enuciated by Ollennu J.A. as set out above were too stringent and not supported by any authority. The analogy drawn between customary adoption and the entirely different concepts of severance of family ties and alienation of property was untenable; and the three cases cited by him were distinguishable, since they dealt with neither adoption nor the disownment of a member of a family but rather with the partitioning of joint family property between branches of the family after severance. Nothing was said in those cases about the requisite customary formalities for adoption nor about severance being identical with adoption. With respect, I entirely concur with Apaloo J.A.'s observation in Tanor v. Akosua Koko about the fundamental differences in the objectives and goals of adoption on the one hand and of severance or alienation of family property on the other. As he remarked at p. 460: "In cutting ekar [i.e. in severance] the intention is to disinherit or disown a member who has already been born into a family ... [whereas the] adoption of an infant may be made by a family on grounds of pure humanity, as in the adoption into the family of a foundling (see Poh v. Konamba (1957) 3 W.A.L.R. 74) or it may be made to meet a felt family need as the purchase of female slaves to avoid a failure of lineal descendants. Any insistence on rigid formalities will be self-defeating." I would respectfully add that the facts of the instant case provide another example of a felt need that may prompt a married couple to adopt a child. As the plaintiff explained in her evidence: "we had no issue of the marriage and my husband said we should adopt a child." It is a notorious fact that before the recent introduction of family planning into the country, our traditional society placed a great premium on procreation and large family units. Childless marriages were often regarded as a taboo or else frowned upon; and barren spouses were often pressurised by relations and the in-laws to dissolve their childless marriages and try their luck in new marriages or concubinage. Hence the understandable yearning of a childless couple to adopt a child and thereby save their marriage from possible collapse. One should not, of course, discount the intrinsic pleasure and satisfaction derived by the adopting couple from adoption and from the companionship of an adopted child. The occasions must indeed be infrequent when one finds oneself differing from Ollennu J.A., an acknowledged expert in customary law [p.318] in his pronouncements on customary law. And it is with the greatest deference and respect that I dissent from his four conditions sine qua non of a customary adoption (reproduced supra). My reasons are as follows. Firstly, like the majority of this court in Tanor v. Akosua Koko I am not persuaded by Ollennu J.A.'s argument that customary adoption is analogous to severance of family ties or alienation of family property. The one is conceptually and fundamentally different from the other two; and they are diametrically opposed in the objectives, goals, and legal effect. Secondly, the cases cited by him have no bearing on adoption. Thirdly, his conditions - in particular the third condition - refer almost exclusively to the ceremonial aspect of adoption and overlook the essential requirements going to the validity of the act of adoption. It is true there is an implied reference in his second condition (supra) to the need for the consent and concurrence of the head and principal members of the family or the natural parents, but even that condition is, with respect, obscured by the description of the natural parent as a "species of property." Surely as a legal persona, the natural parent has legal rights (including a right to give away his child in adoption), duties, privileges and obligations towards his child; and it is unrealistic in the context of adoption to regard him either as a "species of property" or else as being "incompetent to alienate his child, another of the family properties." With respect, I agree entirely with this court's prescription in Tanor v. Akosua Koko of only two essential requirements for a valid customary adoption, viz., the expression of the adopter's intention to adopt the infant before witnesses; and the consent of the child's natural parents and family to the proposed adoption. It is unfortunate that these eminently reasonable prerequisites going to the validity of the act of customary adoption were glossed over by Ollennu J.A. Instead, he concentrated on the consent of the heads of the two transacting families given at a joint meeting. Speaking for myself, I do not regard the consent of the adopter's own family as vital for a valid customary adoption, though it is obviously desirable for the adopter to aquaint his own family members with news of any adoption made by him. In this case, the adopting parents were adults, i.e. sui juris; and I do not see the need for the consent of their own families to an act of adoption which was clearly within their legal competence and impinged on their matrimonial relations. With regard to formalities, however, I entirely concur, with Ollennu J.A.'s observation in his third condition (supra) that: "The particular rites and ceremonies may differ from tribe to tribe." To the same effect was the second holding of this court in Tanor v. Akosua Koko (supra) (as stated in the headnote at p. 452): "It was possible that in Akim Abuakwa, in addition to the said essential requirements stated above, adoption was evidenced by the slaughtering of a sheep, the consumption of liquor, the pouring of libation and the placing of the adopted child on a 'family ladder.' But these were unessential frills and an adoption otherwise valid could not be invalidated by failure to perform these frills." [p.319] Ollennu J.A.'s insistence upon a joint meeting of the two transacting families as a sine qua non, is in my respectful view, unnecessary and unduly formalistic. Provided the consent of the child's natural parents and family is obtained - and in my view this can be objectively ascertained or inferred from either their express words or conduct, I for one, would not insist upon a prior joint meeting of the families of the child and the adopters as a condition precedent for a valid customary adoption. I have been unable to discover any justification for this extra requirement in either customary law or on ground of policy. On the contrary, to insist on the consent and concurrence of two or more families is to impose an onerous and, in my respectful view, an unreasonable fetter on the freedom of action of the adult adopting couple in the adjustment of their matrimonial relations. The insistence upon this extra consent of the family of the adopter might most probably frustrate his freely expressed intention and deeply felt intimate need to adopt a child in order to save his childless marriage. As to the legal effect of customary adoption, it is clear that, whether it takes place in a matrilineal or patrilineal community, the legal consequences are the same: Firstly, the adopted child acquires the status of a child of the marriage, and enjoys the same bundle of rights (including rights of inheritance), duties, privileges and obligations as the natural child. Secondly, by virtue of the accomplished act of adoption, the rights, duties, obligations and liabilities of the natural parents of the adoptee become permanently extinguished and devolve on the adopting parents. To sum up, while there may be local variation in the formalities or actual ceremony of customary adoption, the essential requirements and legal effect are the same in both matrilineal and patrilineal communities; the consent of the natural parents and family of the infant adoptee and the expression of the adopter's intention to adopt the infant before witnesses, being the two crucial prerequisites. I recognise the fact that these conditions were laid down in Sarbah's Fanti Customary Laws (3rd ed.), p. 34 and followed by this court in the Tanor v. Akosua Koko - both of them having particular reference to Akan custom. However, it has not been demonstrated that these essential requirements do not hold good under the Ga customary law. I would therefore apply them to the facts of the case; and hold that there was unchallenged evidence of the first essential condition, namely, the public declaration of the adopter's intention to adopt the infant before witnesses. The plaintiff testified about the adoption ceremony before the girl's natural father Mr. Robinson, Mrs. Akrobetu, herself and her late husband, when the latter announced to the gathering his intention to adopt the child of four since he and the plaintiff had no issue of their own after three years of marriage. Her evidence on this vital issue was corroborated by Mrs. Akrobetu, who quoted the exact words of the plaintiff's late husband, viz. - "This is the girl I want to adopt, and Mr. Robinson [i.e., the natural father] likes it." With respect to the consent of the family of the adopted child, it must be remembered that the child originally hailed from a patrilineal family. [p.320] Therefore it is the consent of the father's line which is the relevant consent for our purpose. That her father himself freely consented to her adoption and even participated in it, stood unchallenged on the record and there was no rebutting evidence of opposition from any member of Alice's father's family to her adoption. Indeed the plaintiff stated in evidence that nobody had ever claimed the child as his. I would hold the child's father's consent as crucial in this case. For reasons already stated, I do not regard the consent of the adopter's family as vital. I am fortified in this view by the decision of this court in Tanor's case. Even if I am wrong and it can be shown that under Ga customary law the consent of the adopter's own family is indispensable for a valid customary adoption, I would, nevertheless, hold on the facts of this case that at least one leading member of that family, namely, the codefendant, knew about the accomplished act of adoption at first hand from her brother (the adopter) and acquiesced in it. It would be inequitable and unconscionable to allow her to impugn the adoption after her brother's death. I infer the co-defendant's acquiescence from the plaintiff's unrebutted story about her sister-in-law's visit to the matrimonial home in 1963, a year before her husband's death, when she was informed by her brother that the box labelled "Alice Bart Plange," belonged to "my daughter Alice, I have adopted her." Even though the co-defendant sought and received confirmation from the plaintiff, nevertheless, she kept quiet about the matter. In the court below, the co-defendant neither cross-examined the plaintiff on this episode nor gave evidence. She must, in my view, be deemed to have admitted the truth of the 1963 episode; and it is reasonable to infer from this episode her acquiescence in her brother's accomplished act of adoption of Alice Plange. It is true that the defendant himself denied any knowledge of the alleged adoption in evidence. However, under cross-examination, he admitted having "seen Alice with his brother for the past fifteen years." I would of course not deduce his acquiescence in Alice's adoption from this equivocal piece of evidence. Suffice it to say that a leading member of the adopter's own family, like the codefendant, a sister of the whole blood, acquiesced in Alice's adoption during the adopter's lifetime, even though I would not elevate the consent of the adopter's family into an indispensable condition for the validity of customary adoption. In his fourth condition (supra) Ollennu J.A. stated that "where a person already belongs to a family there is no necessity for a member of the family to adopt him." (The emphasis is mine.) Presumably the learned judge was driven to this conclusion by his categorisation of adoption as being analogous to the severance of family ties or the alienation of family property; in particular, by his view that adoption involves "the uprooting of a person from one family and his transplantation into a new family." For my part, I cannot see any objection on grounds of either customary law or equity or even logic to an adult member of one family adopting an infant belonging to another family, provided the necessary consents of the child's natural parents and family are obtained and there is clear [p.321] evidence of a public declaration of the adopter's intention to adopt before witnesses. Where, as in this case, the intending adopter's own marriage is childless and the natural father consents to his infant child being adopted by his brother-in-law and maternal halfsister, and the natural mother is also a consenting party, I personally can see no possible bar in customary law to such an adoption, which is also acquiesced in by the natural family of the adoptee. Besides, the question whether or not there is a necessity for adoption in a particular case, deserves, in my respectful opinion, to be considered primarily from the view-point of the intending adopter and not from the angle of the adopter's family; for it is, after all, the adopter who takes the initiative to adopt in response to a felt need. The adopter being sui juris, is legally responsible for his own actions; while the adoptee on account of its infancy and legal disabilities is under the control and dominion of its natural parents and those like the members of its family who stand in loco parentis to the infant adoptee. With regard to the learned judge's conclusion that the evidence adduced by the plaintiff merely established the fact that Alice was a foster child of the plaintiff and her late husband, I would remark that the case was fought on the basis of adoption vel non with the plaintiff affirming and the defendants denying the fact of Alice's adoption. The defendant himself merely denied knowledge of the alleged adoption; his defence was not that Alice was the foster child of his late brother. The co-defendant elected not to give evidence and therefore did not subject herself to cross-examination, even though the plaintiff in evidence had alleged that she was distinctly informed by her brother in 1963 about his adoption of Alice. Again, one should not ignore the telling effect of the unchallenged evidence of the adoptee herself. She gave her full name as "Alice Bart Plange" and stated solemnly in evidence that she knew the plaintiff as her mother; and that she grew to know her as her mother and the late Kojo Bart Plange as her father. It is also significant that she dropped her natal name of Mary Anthonell Robinson and was renamed Alice Aku Bart Plange on being adopted. Exhibit A, her school fees receipt dated 16 January 1962, confirms the fact that her official Christian name in 1962, ten years after the alleged adoption, was "Alice" and not her natal name of "Mary." I hold that exhibit A is some corroborative evidence tending to support the plaintiff's case that the girl was renamed "Alice" on her being adopted. In my considered view, the ceremony of adoption as recounted in evidence by the plaintiff and her witness (Mrs. Akrobetu) sounds reasonable. It followed the general customary pattern of invoking the blessing of the ancestral spirits on the solemn act about to be performed through the pouring of libation. The handing over of the child by its natural father to the adopters through its family representative (Mrs. Akrobetu) was at once symbolical of the natural father's renunciation of his parental [p.322] responsibilities for the child and of the vesting of same in the adopter; while the renaming of the child with adopter's patronymic name put the final seal on a valid act of adoption. I would therefore conclude that Alice Bart Plange was in fact adopted in 1952 under the customary law; and that she was an adopted issue of the lawful marriage of the plaintiff with the deceased Kojo Bart Plange. I would further hold that the plaintiff, as the lawful widow of the deceased, is entitled to one-third share of his estate; and that Alice Bart Plange being the adopted child of the couple married under the Marriage Ordinance, Cap 127, is the lawful issue of the said marriage under section 49 of Cap. 127. By virtue, of section 48 of the same Ordinance, as judicially interpreted in Coleman v. Shang [1959] G.L.R. 390, C.A. and [1961] G.L.R. 145, P.C. the plaintiff and Alice Plange are entitled to two-third share of the estate of Kojo Bart Plange (deceased). Acting under section 79 of the Administration of Estates Act, 1961 (Act 63), I would hold that the plaintiff, as widow, and the defendant, as customary successor, are jointly entitled to the grant of letters of administration in respect of the estate of Kojo Bart Plange (deceased). In the event, I would allow the appeal. JUDGMENT OF SOWAH J. A. Post mid-twentieth century Ghanaian society is still essentially rural and the urban cities aside, the ordinary rustic still thinks in terms of the family as the hub of socio-economic life. A birth in the family is broadcast to all members of the family and amongst the Gas a special ceremony is performed in the naming of the child, at which almost all the important members of the family are expected to be present. The adult life of a member is not altogether free from control of the elders of the family; if the member is a woman, she cannot marry without prior consent of her family even though she might be of age. The destitute is the responsibility of the family; there being no state or old age pensions or social security benefits. Upon the death of a member, even a rich member, the family bears the funeral expenses. It is therefore natural to expect that the principal members of the family ought to be made aware when an unnatural addition is being made to the membership of the family. The issue here is what are the essentials of a valid adoption at customary law? Are they so formalised as to make any variation in the act of adoption invalid? It has been said that native custom consists in what is reasonable in the particular circumstances of the case. The test therefore as to whether the essentials of a particular custom are reasonable or not must be carried out within the context of rural society. In this case, would the average rural dweller consider it a reasonable requirement that the family should at least be informed when a new member, albeit a juvenile, is being introduced into the family who would acquire all the rights, privileges and obligations inherent in the membership of the family? The answer would be in the affirmative. In a wealthy family, upon adoption, the adoptee may succeed to family property; he may even at majority, with permission [p.323] of the head and consent of the principal members of the family, acquire usufructuary rights over family property. In my view it seems reasonable for our ancestors in the olden days to insist that a stranger or a juvenile who is being introduced, assimilated and made a member of the family should be so made with the consent of the head and principal members of the family. But time changes and the society of the nineteenth century is different and a far cry from the present day society. Individual ownership of property, as it is known now, was unheard of. Be that as it may, I think our customs must consciously be imbued with vitality to accommodate the changing times, for strict adherence to old customs which were useful 100 years ago, will only atrophy them. It seems to me sufficient under modern conditions, if the family of the adopter was made aware of the intention to adopt and did not raise objection. The family could of course refuse its consent so as to make the new member ineligible to succeed to family property; notwithstanding its refusal however, the adopter ought to be able to carry his intention into effect. Indeed the adopter can now do so under the Adoption Act, 1962 (Act 104), without obtaining the consent of his own family. The parents of the juvenile adoptee must give their prior consent in a positive manner in order to make valid the adoption of their child. I have had considerable doubt as to whether the family of Plange knew of the adoption or whether there was sufficient evidence of such knowledge; however, upon reflection, and in the interest of the child, I will fall in with the views of my brother Anin. For the child's evidence was positive that she knew of no other parents than the deceased and his wife as her father and mother; they have nurtured and educated her all her life and had even given her a new name. Perhaps if this were an action for succession to family property, one might demand a much higher standard of proof. Accordingly I will cast my vote for allowing the appeal. JUDGMENT OF FRANCOIS J.A. I also agree. DECISION Appeal allowed. S. Y. B.-B.