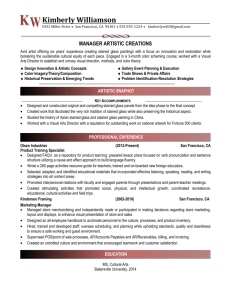

File - Sue Cole. Stained Glass, Drawing and Painting.

advertisement

Wood, glass, geometry – stained glass in Iran and Azerbaijan By Marina Alin on January 21, 2014 in Crafts, Wood Work · 4 Comments In this article I am sharing my experience of visiting traditional stained glass workshops in Iran and Azerbaijan. I am not aware if this kind of craft is unique for the region I am writing about or it can be found in other Islamic countries. If you have more information than I do, could you possibly let me know. Shebeke from National museum of history of Azerbaijan in Baku Window where small pieces of glass were joined together with some kind of binder firstly was a result of technological restriction – craftsmen did not know how to make a large piece of glass. Then the idea of making a decorated window out of coloured pieces of glass painted with religious motifs and combined in way to form a picture popped up. Traditionally in stained glass windows of Catholic cathedrals in Europe strips of lead were used as binders. The technique of stained glass production in Azerbaijan and Iran is different from European. Instead of lead, strips of wood are used. A strip of wood has channels where glass is inserted. Channels are normally used in traditional woodwork to connect up two pieces of wood together without using nails. The glass is placed inside channels and wooden strips are glued together. The width of a channel is equal to the glass thickness. In the past a 3mm-thick glass was used, but now it is mostly of 5 mm thickness. A panel of wooden stained glass is solid and durable; it can stand a stroke of a man or a strong wind. The design of wooden stained glass based on geometry of a square or a triangle is widespread. Colours are very bright greens, reds, blues and yellows. Sometimes colourless glass is used. In Azerbaijan wooden stained glass is called ‘shebeke’. Basically, ‘shebeke’ is a stone grill, but this term is also used for the wooden grill. In Azerbaijan ancient town of Sheki is a centre for shebeke production and restoration. Sheki Khan Palace built in 18th century is lavishly decorated with shebeke. Along with geometric shapes there are biomorphic rhomb-shaped motifs. The work is really intricate – some of the constructions are smaller than a female’s hand. In Iran wooden lattice windows was used as an architectural feature in all kinds of buildings. Magnificent Nasir al-Mulk Mosque in Shiraz built in the 19th century is famous all over the world for its stained glass decoration. Ali-Qapu palace and coffee house in Shesh Behesht garden, Madar-e-Shah medresse, old mosques in Isfahan – all of them have wooden grills on their windows. In Iran I noticed that the glass is placed behind the lattice. I guess that it is a result of lattice restoration and historically glass was placed inside wooden cells. The spiritual meaning of a stained glass lattice window most likely comes from a contrast between light and the absence of light. Light reveals shape and colour; light makes things possible and represent Divine enlightenment. Practically the widespread use of wooden grills (as all other kinds of grills) in Islamic countries can be explained by the need for protection from a daytime heat. It is one of the features that traditional Islamic architecture has in order to help people to feel comfortable inside the building despite on the temperature outside. The skill of wood windows production and restoration is transferred from father to son. When I was searching for information about shebeke in Azerbaijan I came across an article written in 1977. It was about Sheki master craftsmen whose name was Ashraf Rasulov and his teenager son Tofik. In this article Ashraf says that there are 16 different types of shebeke patterns in Sheki Khan Palace. Among other shebeke constructions from Sheki Khan Palace that Ashraf restored was a little door. The quantity of wooden pieces he needed to carve out for this door was about 14000! He tried different kinds of wood and found out that beeсh wood and sycamore tree are the best for refine carving. Ashraf’s son Tofik Rasulov, who is about 50 now, is the only master in Azerbaijan who knows the secret of shebeke craft. He kindly showed us around his workshop nearby Sheki Khan Palace and the technique of shebeke production. Another wood workshop that we visited – Ghaznavi – is in Isfahan. It is run by a master craftsman and his son. Both master craftsmen have at least one student to teach and it gives hope that the craft will stay alive. I want to thank Farkhondeh Ahmadzadeh for the trip to Iran, Asmer Abdullayeva for the trip to Sheki and Roya Mai Souag for her photos. Stained glass in Dolat Abad garden wind tower building in Yazd, Iran Nasir Al-Mulk mosque in Shiraz, Iran, 19th century. Photo source – raweesh.livejournal.com Sheki Khan palace interior, 18th century Shebeke and wood workshop in Sheki Wood workshop Ghazavi in Isfahan, photo by Roya Mai Souag Shebeke and wood workshop in Sheki Wood workshop Ghazavi in Isfahan Wood workshop Ghazavi in Isfahan Wood workshop Ghazavi in Isfahan Wood workshop Ghazavi in Isfahan, photo by Roya Mai Souag Shebeke door decoration in Baku, Azerbaijan Shebeke in Sheki Khan palace, 18th century Sheki Khan palace interior, 18th century, photo by gdruslan Shebeke in Sheki Khan Palace, 18th century Sheki Khan palace interior, 18th century, photo by Peretz Partensky – Creative Commons license Sheki Khan palace interior, 18th century Shebeke from National museum of history of Azerbaijan in Baku Sheki Khan palace interior, 18th century Window in Medresse Madar-e-Shah, Isfahan. Photo by Roya Mai Souag Window in Zayed mosque in Isfahan Window in Zayed mosque in Isfahan Window in Shesh behesht garden coffee house, Isfahan Window in Shesh behesht garden coffee house, Isfahan. This photo shows that the glass is behind the wooden lattice Window in Ali-Qapu palace, Isfahan Window in Ali-Qapu palace, Isfahan Shebeke master Tofik Rasulov at the entrance of Sheki Khan palace Shebeke master Ashraf Rasulov, the father of Tofik Rasulov, in 1977. Photo source – www.vokrugsveta.ru