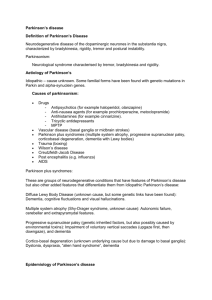

Drug treatments for Parkinson`s booklet Word version

advertisement