Doctors debate hepatitis risk from old blood transfusions

advertisement

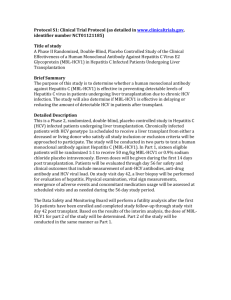

Doctors debate hepatitis risk from old blood transfusions Associated Press - New York Author: LAURAN NEERGAARD, Associated Press Writer Date: Aug 10, 1997 Text Word Count: 695 Document Text WASHINGTON (AP) - The government is considering whether to issue public warnings that people who had blood transfusions before 1990, and some who got blood even more recently, are at risk for hepatitis C. An estimated 290,000 Americans got the serious liver infection from transfusions before purity tests begun in 1990 dramatically lowered the chance of infection from donated blood. The government never notified Americans who received blood before 1990 about the risk and has no method of tracing a smaller number of blood recipients put at risk by possibly tainted blood after then. Authorities face two questions: How many of the hepatitis patients know they're infected? How can the others be tested? This week, a government-appointed panel of liver experts and ethicists will debate those questions, considering whether to advertise the liver risk or undertake the more expensive and difficult task of mailing warning letters to possibly millions of transfusion recipients. "Why shouldn't these people be told?" asked Dr. Eugene Schiff of the University of Miami, a member of the Public Health Service's blood safety advisory committee. "They at least ought to have the opportunity to look at (treatments) that might help them." The panel remains divided, Schiff admitted, but he supports sending warning letters to everyone the government can track down who had a potentially risky transfusion. "A letter would have a bigger impact than just a public service announcement," he said. "A letter in the mail would shake you up." Not necessarily, warned fellow panelist Dr. James AuBuchon of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. Efforts in the 1980s to test certain blood recipients for the AIDS virus and a Cincinnati blood bank's private attempt at hepatitis C testing had few takers. "When people feel healthy, they tend to ignore any message to the contrary," AuBuchon said. About 4 million Americans have hepatitis C. Many don't know they're infected because they experience few if any symptoms for many years, but others develop serious, even fatal, liver disease. Tainted drug needles cause the vast majority of hepatitis C. But new research, which suggests people who catch hepatitis C from blood are especially vulnerable to liver failure, is sparking a renewed push to somehow notify people at risk. "The question is not whether to identify people with hepatitis C infection. The question is how best to do that," Dr. Jay Epstein of the Food and Drug Administration said. The FDA is awaiting the blood panel's recommendation. The risk from a blood transfusion today is very small - between 1 case in 10,000 donations and 1 in 100,000 donations. But 290,000 people caught hepatitis C from transfusions before blood banks began purity testing in 1990. And the first test needed improvements, so it wasn't until 1993 that blood banks had highly effective screening. Finding many people who had risky transfusions could be impossible. Hospitals are required to keep transfusion records only five years, so the FDA might be able to trace recipients only back to 1992. Many already have died of the condition that required the transfusion in the first place, Epstein said. Identifying all recipients of blood donated by a person with hepatitis C would cost about $137 per donor, AuBuchon said his preliminary calculations show. Then each recipient, if still alive, would have to be traced. There's a trickier problem of how to treat the newly diagnosed. Drugs cure only about 20 percent of hepatitis C patients. Nobody knows in advance who will be helped, and many people who received blood years ago may be too old to withstand the treatment's significant side effects. Some doctors say the most cost-effective plan is to simply issue public service announcements alerting people to see a doctor if they had a blood transfusion prior to 1990 or perhaps 1993. The American Liver Foundation already has begun a nationwide hepatitis education campaign - complete with posters of people with yellow eyes, an exaggerated depiction of jaundice - that urges people at risk for any reason to be tested. Separately, the government is educating doctors about hepatitis C testing and treatment. "It's how many people are going to be helped" that will guide the blood panel's next step, AuBuchon said.