TAKE A WALK THROUGH A POLISH CEMETERY

advertisement

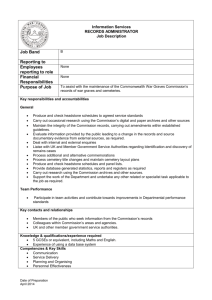

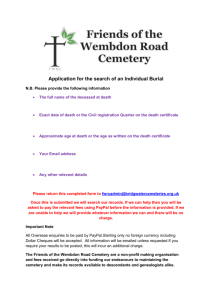

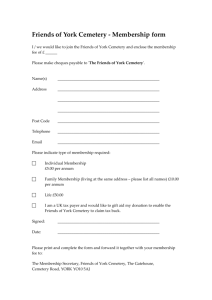

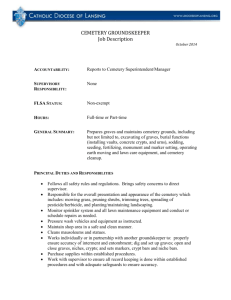

TAKE A WALK THROUGH A POLISH CEMETERY by Aleksandra Kacprzak Aleksandra Kacprzak is our Polish correspondent in Europe. A seasoned researcher who speaks English, she resides half the year in Connecticut and the other half in Grudziądz. For information on her research services, please contact her at alex@genoroots.com . Before we depart on our fascinating little trip to the places of rest of our ancestors, a place where we often feel how wonderful it is to be alive, a few dictionary-like definitions are in order. A cemetery is “... a place frequently protected by a wall where in single or group graves, the deceased or their ashes, after cremation, are laid to rest.” The Polish word cmentarz derives from the Latin coemeterium (which in turn was taken from the Greek koimeterion.) This Greek word is the equivalent of the Latin dormitorium, a place of sleep and rest. In Polish the word underwent several “evolutions.” In old Polish, there were quite a few variants of the word derived from various pseudo-Latin expressions, ranging from cimiterium, cinterium, cimitertium to the more Slavic sounding cmyntarz, smentarz or smyntarz which, more likely than not, came from the word smętny, meaning melancholy or sad. Some of these words can still be heard today in rural dialects spoken in Poland. As usual, the English language is both more varied and precise. Aside from the standard cemetery, which has the same root as the Polish version, we also have such descriptions such as burial ground, graveyard, and necropolis, plus churchyard to describe a cemetery adjacent to a parish church. The history of cemeteries is inexorably linked to the history of religion and culture. What is constant is the respect for the dead. The outward manifestations of this respect have changed numerous times throughout the centuries. In very distant times, when forest-dwelling Slavic tribesmen inhabited what was to become Poland, one of the customs they practiced was the burning of the bodies of their brethren. The ashes were then sprinkled in the fields or placed in burial urns—Slavic face urns are one of the most beautiful manifestations of folk art. The most distinguished and important members of the tribal community frequently were interred in a burial mound in which various tools and household objects were placed for the use of the deceased in the other world. These customs were radically changed with the acceptance of Christianity. Bodies were now buried on consecrated ground in the immediate vicinity of a church. In the Middle Ages, we can observe the first cemeteries which were located outside the city walls and had the appearance of small parks. In many cases, they were designed by architects, such as the Powiązkowski Cemetery in Warsaw and the Rakowicki Cemetery in Kraków. In these two burial grounds rest noted personages from the world of politics, culture and the arts. Another type of cemetery is a military burial ground erected on the sites of well known battles. These types of cemeteries are especially numerous in Beskid Niski. At times there are individual or mass graves containing the names of those who fell in battle, which, of course, have some informational value for the family history researcher. However, many military monuments contain no names but stand as a monument to those who gave their lives and whose names are lost to the ages. Thanks to its very nature, a cemetery is a personal chronicle of the history of a given locality. It is a witness to the past, a link between that which has gone before us and the present. It is a place that lets us learn about the fate of an individual and at the same time bequeaths to us an image of the culture and practices of the entire community of a given region at a certain point in time. But enough of generalities for now. It is time to actually visit a cemetery. For some it will be a walk to a land of remembrances and memories of the deceased; people we knew and with whom we spent a portion of our lives together. For others, it will be a time for meditation about the sense of life, of passage and about our place in the universe. For mortuary historians, the grave types will speak to them about changes in artistic style and customs. Linguists will observe archaic language and phonetic changes in forms of names. And for genealogists, a walk through the cemetery is a priceless information source; a place we can find links to the branches of our family. A genealogical expedition to the cemetery requires appropriate preparation. We should try to anticipate all eventualities. Step One – Find out about the nature and size of the cemetery and if there is an office which keeps records of burial. Step One is usually Problem One! I have visited numerous cemeteries in rural areas and have spoken with dozens of priests and have yet to find any such cemetery records. I speak here of records showing the location in the cemetery where individuals are physically located, not the church burial registers. In rural areas, people have been burying their family members in the same plot for generations. They know where there gravesite is as this information is passed down from generation to generation in a family. If you have living family members, they will know where your ancestral family plot is located. If you are not aware of any family members that could point you in the right direction, and if you are dealing with a relatively small locality, you can surmise that there is probably only one funeral home in the area. Speaking to the owner of the funeral home may prove fruitful as they may have the names, addresses and phone numbers of persons with your surname of interest that recently buried someone in their family. Similar information may also be obtainable from the stonecutter which serves the area. Stonecutters have been especially busy in recent years as it is now fashionable to “rehabilitate” old gravestones, or transfer family members’ remains to a family plot. These changes may just be our salvation in finding living family members if they contracted for such a service. The destruction of old gravesites, of the historical old crosses, metal plates and the like, tug at the heart of the lover of history. If you glance in some remote corner of the cemetery, more likely than not, you will find a pile of old grave markers. People do not want to keep them but at the same time many cannot bring themselves to discard or destroy them. Thus, they stand against a cemetery wall, a testimony to the past (see photo at left). New sections of rural cemeteries are generally orderly, with rows of carefully arranged stones. However, this is definitely not true in the older parts of the cemetery, which are centuries old. There may be a few horizontal rows, then vertical rows, then no rows, merely a hodgepodge of gravemarkers of all types pointing in all directions. Walking (more precisely, climbing) over the stones can be difficult and physically challenging. Some graves will be buried in thick undergrowth deep within bushes or trees. These are usually the graves of families that have died out or have immigrated to another country. In general terms, the most we can hope for in a non-historically significant, rural cemetery are readable gravestones from the 18th century and beyond. This, of course, does not apply to crypts where kings, aristocrats, and church officials lie in repose. These are much older monuments, and our ancestors did not belong to this illustrious group of VIPs. Many earlier graves were marked with wooden crosses which quickly degenerate. The earliest cross of this type I have ever found with a legible inscription dated from 1953 (see photo below, at left). Marble and limestone grave markers are often hard to read as well, as their inscriptions may have been washed out by rain. Sandstone grave markers begin to crumble, metal plates rust and copper, and bronze markers are also subject to destruction. Cast iron and granite stones are the most lasting, and I have seen such markers of considerable age in rural cemeteries that are well preserved and totally legible. These warnings should not deter us however from searching for ancestral graves. The researcher’s determination and passion within us will keep us going and make the search into the jumble of stones an exciting expedition. Step Two – Preparing our “equipment.” A serious trip to the cemetery requires us to be well prepared and to take items with us that may be needed to insure the successful harvesting of information. Among the objects that we should consider bringing with us are: • a hard bristle brush, but it should not be made of metal or copper wire. We do not, under any circumstances, want to contribute to the further destruction of delicate inscriptions. • a tooth brush • a trowel to clear away moss and dirt • • • • • • spray bottle with water and a rag clippers to cut grass or branches pads, writing implements larger sheets of paper and coal or chalk to trace illegible inscriptions aluminum foil, which can serve as an impromptu “mirror” and allow different lighting and shading. Looking at inscriptions from different angles may enhance their legibility. A high quality digital camera. A good camera will produce postcard like clear images and not only give us an image of the stone and what is carved into it, but allows us to photograph photos of the deceased which appear on many stones. It may turn out that these are the sole and only photo of a given individual that may exist (see photo at left). Some additional hints – Our own fingers and sense of touch can also help in deciphering illegible inscriptions by tracing the letters with our own hand. Also do not forget to record the name of the company that produced the stone or cast iron plate, which is sometimes noted. Although the firm may have gone out of business a century ago, there may still be some archival records with valuable data. Also, you will note that in some parts of Poland, it was customary for the person who paid for and erected the monument to have their name recorded in the stone [fundator (m) or fundatorka (f)]. In nearly all cases this individual will be a close family member and we should take note of these names. In the case of recent burials, families often leave mounds of artificial flowers, wreaths and commemorative ribbons on the gravesite for months after a person is buried. The names of the persons who brought the flowers appear and we can glean information from them. Often family relationships are delineated – such as “from grandchildren – Oleś, Janek, Marysia.” Other wreaths will come from co-workers and the name of the firm where they worked with the deceased will be evident – another scrap of information on a relative that we may not have known. If we have an information void as to the descendants of a known relative and have exhausted all other possibilities, we can visit the cemetery on All Souls Day in November. This is the day Poles journey back to their ancestral cemeteries to honor the memories of deceased family members. Invariably someone from the family will visit the grave that day. All you need to do is wait for them to appear to make contact. It sounds like a police stakeout but, if it is your only recourse, you may need to use it. Each cemetery has gates. The gate is a symbol of the passage from one world to the other (see photo at bottom left on page 7) and the cemetery walls separate these two worlds. Other symbols are also able to be observed. Some families carve the deceased’s name on both sides of the stone. This symbolizes the separation of the sphere of the living from the sphere of the dead. The cemetery cross is a symbol illustrating the hope of the resurrection, as is a butterfly, an ancient symbol of the rebirth of the soul and immortality. We can also find symbols of death in the cemetery, the most common being the skull and crossbones and urns (see photo at left). Some families have a clock indicating the time of death and at the same time the first moment of eternal life. A withered tree stump and cut flowers symbolize the impermanence of our lives on earth. Angels with sad faces are a symbol of mourning. Coats of arms, flags and symbols of weaponry pay homage to military figures. Since the demise of Communism, information about relatives murdered by the Soviet (NKVD) or Polish (UB) Secret Police will now appear on grave markers, a testimony to a dark period in Poland’s history (see middle photo on page 7). Likewise accounts of persons executed by the Nazis or Soviets or taken to their death at concentration camps is also evident to in the text of certain inscriptions. In some old cemeteries a person’s final resting place was blended into the environment, as if a part of it, symbolizing the natural order of life and passage into the inevitable beyond. Certain plants carried symbolism as well. These “death plants” included yews and black lilacs as well as linden and spruce trees. The fir tree played the role of an intermediary between man and the supernatural world. Other typical cemetery plants were ivy and boxwood. The most popular ornamental flower utilized to decorate graves was the pansy, a symbol of remembrance and thought about the deceased. In today’s world, many have forgotten the historical symbolization of these plants. They are now used exclusively for decorative purposes and in many cases are of the “made in China” variety. A symbol of our times is virtual reality. This includes cemeteries as well. You can erect a virtual gravestone and light a virtual candle or even place virtual flowers in a vase. Only the fees for such services are real. The only positive thing about these virtual “burial grounds” is they can serve as an information source. However, instead of this, I invite you to visit an old (and real) Polish cemetery. I guarantee that the satisfaction you will experience from what you will discover will be much better. And real it will be – the scratches on your leg from the bushes, brambles and prickers will let you know that. And the candle that you light at your newly found ancestor’s grave will be real as well.