Theories in Education

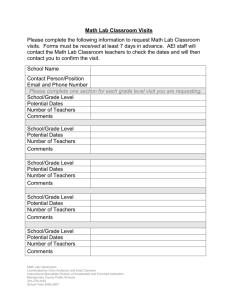

advertisement

A Look at Two Influencing Theories in Education: “Core Knowledge” of E.D. Hirsch and “Accelerated School Project” of Henry Levin Lynne M. Bailey EDU 35 Fall 2002 Prof. Ross L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 2. Core Knowledge .......................................................................................... 2 3. Accelerated Schools Project ....................................................................... 5 4. Additional Discussion Points ....................................................................... 7 5. Bibliography ...............................................................................................13 6. Appendix ....................................................................................................16 (ii) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross A Look at Two Influencing Theories in Education: “Core Knowledge” of E.D. Hirsch and “Accelerated School Project” of Henry Levin 1. Introduction Debate over schooling is nothing new1, but especially in the last decade we have witnessed an unprecedented rise in the development and implementation of educational programs seeking to improve learning processes and student performance. This includes a shift towards whole-school reform and the establishment of comprehensive programs propelled by the particular founder’s idea of how an ideal learning environment should be structured and influenced by differing educational and psychological learning theories and practices. This paper will review the philosophies and programs of E. D. Hirsch and Henry M. Levin, founders of the Core Knowledge and Accelerated Schools programs, respectively. Both of these initiatives are driven, at least in part, by the desire to improve education in under-served, at-risk school populations. The availability of U.S. government education policy and funding2 has propelled the implementation of these and other models across the country. 1 “The Story of Public Education”, History Page 2 Fashola & Slavin, p. 1 (1) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross 2. Core Knowledge The educational reform movement, Core Knowledge, is traditional by nature and is based on content, not process. It seeks to ensure a solid and fair elementary education for all students by using a grade-by-grade specific, shared core curriculum to help children establish strong foundations of knowledge. The content of this core curriculum is outlined in two books – the Core Knowledge Preschool Sequence and the Core Knowledge Sequence, K-8- and states explicitly what students should learn at each grade level. Exact figures about its usage vary depending upon the source, but there appears to be about 1,000 schools in the United States are participating in school model3. In 1986 E. D. Hirsch, Jr. established the non-profit Core Knowledge Foundation. His philosophies are best expressed in his books, principally “Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know” (1987) and “The Schools We Need and Why We Don’t Have Them” (1996). In an earlier book, “Philosophy of Composition,” we find the essential kernel of his thinking – “the reason students wrote such poor essays was not that they lacked competency in writing skills, but that they lacked the background knowledge assumed by questions. They couldn’t answer a test question about the Civil War because they didn’t recognize the names Grant and Lee.” 4 The basic tenet of Core Knowledge therefore, is this fact-filled curriculum. The center of the model is the Core Knowledge Sequence, a “spiral” of specific information which builds towards broader and deeper knowledge, one where first graders would know the story of the 13 colonies and older students more of the whys and wherefores. This principle applies to all subject areas – English, mathematics, science, music and visual arts. Hirsch argues 3 Core Knowledge web site, “Frequently Asked Questions,” http://www.coreknowledge.org/CKproto2/about/FAQ/information.htm#1 4 Traub, “Better By Design,” p. 31 (2) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross that in a democracy, general knowledge should be a primary goal of education, that knowledge is the great social equalizer. It provides a foundation for competency, and regardless of race, class, or ethnicity, paves the way for a more just society. 5 Central to the philosophy is that knowledge begets more knowledge. We learn by building on what we already know. Hirsch claims “there is a consensus in cognitive psychology that it takes knowledge to gain knowledge,” and points to research conducted by Prof. George A. Miller, Herbert A. Simon and Jill Larkin, Betty Hard and Todd Risley (“Meaningful Differences”), Thomas Landauer and D. Lubinski and L.G. Humphreys. This research highlights that vocabulary in particular is a reflection of knowledge. It is estimated that you need to already know 95% of the words in what you read or hear to comprehend the information. Therefore, the child with the better vocabulary will naturally learn more than another child with a weaker vocabulary. 6 By using a Core Knowledge curriculum, the disadvantaged child will have the opportunity to catch up to the advantaged child. This extensive curriculum (see appendix for an outline of study for grades 6-8 on page 24) started with a list made by Hirsch and his colleagues of what literate Americans do know and was part of his book, “Cultural Literacy”. 7 The Core Knowledge Sequence has evolved and now represents the result of research into the content and structure of the highest performing elementary school systems around the world. Efforts have been made to refine the curriculum by wide-ranging consensus-building among diverse groups and experts from the Core Knowledge Foundation's advisory board on multicultural traditions. At a national conference in 1990, twenty-four working groups hammered out a draft sequence. Further fine-tuning was accomplished during a year of implementation at Three Oaks Elementary in Ft. Myers, Florida and as more schools adopt 5 Hirsch “Why General Knowledge Should Be a Goal of Education in a Democracy” 6 Hirsch, “You Can Always Look It Up—Or Can You?” 7 Traub, “Better By Design”, p. 32 (3) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross Core Knowledge, the Foundation claims to seek out their suggestions based on their experiences to update the Sequence.8 Hirsch is especially critical of the progressive movement in education. In his book, “The Schools We Need and Why We Don't Have Them,” Hirsch concludes that "educational progressivism is a sure means of preserving the social status quo" and that educational conservatism offers the "only means whereby children from disadvantaged homes can secure the knowledge and skills that will enable them to improve their condition." It is impossible to expect higher achievement in specialized areas unless youngsters learn such basic skills as reading, writing and math. It is his contention that educational progressivism has stunted this realization of basic skills because it puts other issues, such as self-esteem and the "joy of discovery", first.9 Hirsch does not, however, advocate a particular style of pedagogy and many studentcentered activities, the cornerstone of progressive ideologies, are employed by the various schools subscribing to his theory. The difference is, of course, that the topics covered are not chosen by the students, and the activities are very much coordinated and guided by the teacher. He also does not condemn direct, teacher-led instruction or memorization of the multiplication tables. As there are schools implementing the Core Knowledge model, it is appropriate to ask about results. Some research has been done to assess the success of the model, but more needs to be done. Indications are, however, that the students from Core Knowledge schools are doing better on standardized tests. Anecdotally, there is much enthusiasm for the model, and teachers are free to use a variety of techniques to teach the curriculum, and do—everything from cooperative learning to lectures. 8 Core Knowledge web site, “Who Decided What's in th Sequence?” http://www.coreknowledge.org/CKproto2/about/index.htm#WHO 9 Thomas B. Ford Foundation web site “Other Education Issues – Curriculum and Content”, http://www.edexcellence.net/otherissues.html (4) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross 3. Accelerated Schools Project The Accelerated Schools Project (ASP), championed by Henry Levin, stemmed from his analysis of school reform literature: that virtually all programs for disadvantaged children were remedial in nature and that children so designated remained in basically remedial programs for their entire school career. His program rejects that thinking entirely, and places all children in an enriched learning atmosphere. Levin claims we should expect just as much from these children as we do from any others. In a 1992 interview Levin stated that when “you start with their [children’s] strengths and build on those strengths, you’re challenged to come up with enrichment for their gifts and talents.” “I don’t like term ‘at risk’. As soon as you think of kids in need of repair, what you do is repair.” 10 The remedial process precipitates a cycle of lower expectations, lower achievement and often emphasizes repetition and basic skills, ignoring more progressive teaching techniques.11 Perhaps drawing directly on Howard Gardner’s philosophies, every child is treated as a gifted child. Eclipsed in size only by the Success for All program, ASP has been adopted in over 1,300 elementary schools12. The program began in 1986 when Levin, along with graduate students from Stamford University, enrolled two schools in the San Francisco Bay13 area to start putting his philosophy into practice. A whole-school model evolved coupling a strict plan for school governance with enriched and “powerful” learning. The three essential principles are: 1) unity of purpose, 2) empowerment with responsibility and 3) building on strengths. Levin strongly believes that to change the classroom, the whole school structure has to change as well, from the top down, to a more democratic, consensus building model. His 10 “Accelerated Schools Project,” Teacher Magazine 11 Traub, “Better By Design” p. 13 12 Viadero, “As Levin Steps Back..” 13 “Accelerated Schools Project,” Teacher Magazine (5) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross program requires that the school community works together to transform its school. As a group, teachers, parents, administrators and students work together to examine the way learning and teaching take place, then develop a shared understanding, or school vision, to encompass the kinds of educational experiences it wants its students to have and decides how best to address these goals. A school will not be accepted into the program unless at least 90 percent of fulltime staff and school community representatives are willing participants. The term "big wheels" refers to this formal processes of becoming an accelerated schools: taking stock, forging a vision, setting priorities, forming governance structures, and using the Inquiry Process to bring about institutional changes by the collaborative efforts of the whole school community.14 The ASP is a continuing effort to align the vision with reality. Cadres (committees) are formed from the entire school community and use a systematic problem-solving process, “Inquiry”. Members work together to find the best possible solutions to challenge areas they have identified. These challenges often address the what, how, and context of students' learning. For example, the Curriculum Cadre in a California school was looking at why the current reading program was not working well. Together they defined the problem more closely, tested their hypothesis, and concluded that there was little connection between reading and language arts across grade levels and that left students disengaged. An action plan was developed, focused on using the performing arts to strengthen language arts and reading. This approach could draw on different student learning styles and build upon their strengths and interests. Working with this idea, the school then hired a performing artist to work with teachers and the school's artistin-residence to integrate what students are learning in the classroom with the arts.15 This process is central to the ASP concept: a democratic, participatory structure that is committed and empowered to bring about their shared vision. 14 Accelerated Schools Program web site, “Frameworks for Learning and Instruction” at http://www.acceleratedschools.net/main_pow.htm 15 Accelerated Schools Program web site, “Frameworks for Learning and Instruction” (6) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross But even as Levin defined the school structure, he did not initially dictate pedagogical technique. He went on to coin the term “powerful learning” which he felt the new school climate fostered. Though there is no direct corollary from democratic structure to constructivist learning, he believes that this is a natural outgrowth. Once the climate of teamwork is established in the school, innovative teaching practices can be widely implemented. Levin cites five qualities of powerful learning. It is authentic, interactive, learner-centered, inclusive and continuous or open-ended. He favors an interdisciplinary curriculum and sees powerful learning as an environment that integrates curriculum, teaching and context for the student learning experience.16 In practice, it does appear that most schools adopt a constructivist approach. There is a reading program developed by ASP, the Accelerated Reading Renaissance program, which runs through the third grade. Other than that, however, powerful learning is up to the individual schools and teachers. 17 What about results? Levin himself did not see his program as a quick fix, but rather a 30year project.18 Indeed initial results were mixed. This past year, however, the Manpower Demonstration Research Corp. completed a study of Accelerated Schools that shows a definite pay-off over a longer period of time. The main objective of the study was to assess the efficacy of the ASP approach in a small sample of schools that had launched the reform early in its development and served at-risk students. The study is based on eight years of test data from third graders in eight schools across the country that initiated the program in the early 1990’s. The results are encouraging. Students showed marked improvement five years into the program. This was a small study and these schools did not institute any widespread curriculum or pedagogical changes until at least the third year. The biggest gains came from the schools that 16 Traub, “Better By Design,” p. 14 17 i.b.i.d. p. 16 18 “Accelerated Schools,” Teacher Magazine (7) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross had the lowest average test scores before adopting the ASP model. Average test scores increased 7 to 8% in reading and math.19 As might be expected, the ASP model is evolving. The findings suggest that current efforts to speed up the implementation of curriculum and instructional changes are a wise decision. More technical assistance is also available and there is a concerted effort to illustrate power learning techniques and get them in the classroom sooner. Defining the school, it’s objectives, assessing its strengths and weaknesses, listening to all stakeholders in the process, are key elements in the Accelerated School process. Applying the constructivist method in the classroom is what brings it to life and enriches the learning experiences for all students. 4. Additional Discussion Points The concepts that Hirsh espouses are antithetical in many ways to the pivotal ideologies of the progressive movements. The progressives propose student-directed and initiated learning, learning by discovery and directly relating to student experiences. Standards may be adjusted according to a learner’s differences and there is an emphasis on in-depth project work, rather than acquiring a broad-based knowledge base. Students are assessed on portfolios of individual and group work, grades are downplayed, teachers act as facilitators and curriculum embraces a range of issues encompassing a balance of academic and social concerns. The focus in Social Studies is on diversity, multi-culturalism and may neglect historical and geographical facts. Is the pendulum swinging back the other way? In 1960 Jerome Bruner hypothesized that “any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development.”20 Ergo, we should not postpone the introduction of important subjects on grounds that they may be too difficult for the child to learn. Elements of any subject can be taught in some form and even fundamental 19 Bloom, et. al., Executive Summary pp. 1-4 20 Bruner, p. 33 (8) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross principles of the sciences can be simple and intuitive. The matter can be revisited at a later age, in depth and with a higher level of comprehension. Paiget’s Stages of Development can guide us in the manner of presenting information, so that it can be best discerned by the child learner.21 Schools have many social responsibilities as well and it is hard to imagine in an urban school there is enough time in the day to accommodate a curriculum as wide ranging as the one Core Knowledge espouses, but I like the idea very much. I do think that there should be a common curriculum and specific knowledge goals for our students. Whatever goals we have for our students, most require a structure to achieve them. It should not be a guessing game of ambiguous standards – why not specify some of the concrete information we wish our children to know? Yes, of course, we want them also to become critical thinkers and problem solvers, but without a foundation of common knowledge, they are at a disadvantage in expression, comparisons, spontaneous and relevant discourse, and will undoubtedly have more difficulty in researching new information on any given subject if it is all foreign to them. Actually, there is no reason a Core Knowledge curriculum cannot be adopted by an Accelerated School or integrated with other initiatives. Indeed, implementation will always vary, and some programs offer a wide latitude for doing so. It is no secret that an interested, motivated student is going to learn more and than one who is not. The Accelerated School Project is very compelling as well, and if not an influencer, than certainly an early reflector of much greater inclusion in today’s schools and progressive pedagogy. His model also actively includes the whole community to govern the schools. This is a trend tat is percolating through many schools. Levin also seems to embraces the theory of Multiple Intelligences advanced by Gardner—his initial impetus to treat at-risk students as gifted learners reflects that. There is finally some evidence that corroborates progressive methods with better achievement, particularly when coupled with curriculum changes. 21 i.b.i.d. p 34 (9) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross As off-the-shelf school models, these two programs are relatively inexpensive compared to others, and there is ample room for local customization, but implementing their basic learning theories need not require a formal signing up. A School Practices Survey by the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation found that, at least in the state of Ohio, the majority of schools practiced neither traditional nor progressive exclusively. They occupied the middle ground.22 The ongoing influence of progressive models is well reflected, as is the continuing hue and cry of “back-to-basics”. Both Levin and Hirsch have been at the forefront in advancing these ideologies and their impact is keenly felt. There may only be a couple thousand schools using their programs formally, but many more organizations are embracing specific standards, all the while trying to implement constructive teaching techniques to engage and motivate the learner. Do these programs make a difference? Certainly The Accelerated School at the corner of Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard and Main Street, Los Angeles, has made an enormous difference to its neighborhood. Operating as a charter school in one of the most underserved inner-city communities in the country, it was named Time Magazine’s 2001 Elementary School of the Year One of the nation's "most accomplished K-12 institutions"… TAS was chosen for having "found the most promising approaches to the most pressing challenges in education."23 PS 20 in New York City is one school that implements a Core Knowledge curriculum. Social Studies is used as a way to scaffold knowledge, using chronologies and location to build students’ understanding of the world. Parents applaud the curriculum whereby students are 22 Traditional Schools, Progressive Schools 23 “TAS An Introduction.” The Accelerated School (Los Angeles) web site. (10) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross getting a multicultural and interdisciplinary view of the world. Though Core Knowledge programs have yet to prove that Hirsch’s theory that children will master higher level thinking skills through a content rich curriculum, some studies have shown significant gains in reading and math in the early levels and almost all studies have concluded that Core Knowledge studies perform better on content knowledge tests.24 Maybe it’s too early to tell just how much of a difference they make and there are many variables to account for, but recent studies are very encouraging. These models are new and “experimental” Let’s keep in mind, though, that “The mere act of consciously devising a curriculum, and then of connecting that curriculum to explicit expectations, is almost bound to bring improvement—whatever the curriculum, and whatever the expectations. Then there is the galvanizing effect that comes from starting over, at least once teachers and administrators recover from the shock of the new. Indeed, the mere fact of paying concerted attention may make a mediocre school better. And this may help explain studies like those in Memphis which show, in effect, that everything works—up to a point.”25 There seems to be a consensus that too many of our schools are failing, and that as a nation we have especially failed those children from disadvantaged neighborhoods. Government policies are at least making the effort to fulfill the spirit of public education, that there be equal opportunity for learning for everyone. How we can do this most effectively is still undecided, and there is no reason to expect that “most effective” for one child will be the same for every child. But, as Hirsh notes, “Our responsibility as educators is to define the knowledge our students need and – through a lively variety of pedagogical techniques – to help them master it.”26 The debate continues, and with more government funding available demanding empirical data, it will collected and analyzed. There are several difficulties inherent in such 24 Traub, “Success for Some,” p. 31 25 Traub, “Better By Design,” p. 4 26 Hirsch, “You Can Always Look It Up—Or Can You? (11) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross studies. A constant barrage of standardized testing consumes valuable teaching/learning time and resources. Off-the-shelf models will be implemented differently. It may take a greater number of years to fully incorporate and evaluate the effectiveness of the varying approaches. Schools may find that a combination of models is what works best and legislators are impatient for results. The biggest gains have been seen in the most poorly served areas, but results in the general student population are more mixed. I applaud the attention that is trickling down to the at-risk school population, and I have to concur that any committed, sustainable, well-funded effort is bound to show results among those children with the most to gain. I cannot fathom that a one-size-fits-all approach will ultimately be most successful. It is more likely that a thoughtful amalgamation with regional nuances will prevail, and will live side-by-side with a significant number of alternative learning environments. This is not at all bad, for ultimately it provides worthwhile choices for many students. Just as there are multiple intelligences, there are multiple learning styles and our children may be best served by matching their style to the right school. Ultimately, it’s what children do as adults that is the final test of a good education. (12) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross 5. Bibliography “Accelerated Schools (K – 8)” The Catalog of School Reform Models NW Regional Educational Laboratory and NCCSR The National Clearinghouse for Comprehensive School Reform, December 2001. December 4, 2002 at: http://www.nwrel.org/scpd/catalog/ModelDetails.asp?ModelID=1 Accelerated Schools Project web site. December 4, 2002 at http://www.sp.uconn.edu/~wwwasp/index.htm “Accelerated Schools Project.” Teacher Magazine. May 1992. December 2, 2002 at http://www.teachermagazine.org/tm/tm_printstory.cfm?slug=8school9.h03 “Accelerated Schools Project” EdSource Online. 2000. December 2, 2002 at http://www.edsource.org/edu_refmod_mod_accelerated.cfm Bloom, Rock, Ham, Melton, O’Brien, Doolittle and Kagehiro. Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation November, 2001. December 4, 2002 at http://www.mdrc.org/Reports2001/AcceleratedSchools/AccSchools-ExSum.htm Bruner, Jerome S. “The Process of Education”. New York: Vintage Books, 1963. Chandler, Louis, “Traditional School, Progressive School: Do Parents Have a Choice?” The Thomas B Fordham Foundation (1999). December 4, 2002 at http://www.edexcellence.net/library/tsps/tsps.htm “Core Knowledge (K – 8)” The Catalog of School Reform Models NW Regional Educational Laboratory and NCCSR The National Clearinghouse for Comprehensive School Reform, December 2001. December 4, 2002 at: http://www.nwrel.org/scpd/catalog/ModelDetails.asp?ModelID=11 Fashola, Olatokunbo S. and Slavin, Robert E. “Schoolwide Reform Models: What Works?” Phi Delta Kappa International Articles, 1998. December 2, 2001 at http://www.pdkintl.org/kappan/ksla9801.htm (13) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross Hirsch, E. D. Jr., “Challenging the Intellectual Monopoly” From “The Schools We Need and Why We Don't Have Them” 1996. December 4, 2002 at http://www.coreknowledge.org/CKproto2/about/articles/Challengingmonopoly.htm Hirsch, E. D., Jr. “Breadth Versus Depth: A Premature Polarity” Common Knowledge, Volume 14, Number 4, 2001. December 4, 2002 at http://www.coreknhttp://www.edweek.com/ew/vol18/30priv.h18owledge.org/CKproto2/about/articles/breadthvsdepth.htm Hirsch, E. D., Jr., “Why General Knowledge Should Be a Goal of Education in a Democracy” Common Knowledge, Volume 11, # 1/2, Winter/Spring 1998. December 4, 2002 at http://www.coreknowledge.org/CKproto2/about/articles/whyGeneralCK.htm Hirsch, E.D., Jr. “You Can Always Look It Up—Or Can You? Common Knowledge, Volume 13, #2/3, Spring/Summer 2000. December 4, 2002 at http://www.coreknowledge.org/CKproto2/about/articles/lookItUp.htm Keller, Bess. “Levin To Launch Privatization Center at Columbia.” Education Week on the Web. 1999. December 2, 2002 at http://www.edweek.com/ew/vol-18/30priv.h18 Olson, Lynn. “Researchers Rate Whole-School Reform Models.” Education Week on the Web. 1999. December 2, 2002 at http://www.edweek.com/ew/vol-18/23air.h18 The Accelerated School (TAS, Los Angeles) web site. December 4, 2002 at http://www.accelerated.org/03_main/menu.htm “The Story of American Public Education” PBS (2001): Roots in History. December 4, 2002 at http://www.pbs.org/kcet/publicschool/roots_in_history/testing.html based on “School: The Story of American Public Education.” Documentary. Stone Lantern Films, KCET 2001. Thomas B. Ford Foundation web site. December 4, 2002 at http://www.edexcellence.net “Traditional Schools, Progressive Schools: Do Parents Have a Choice.” The Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. December 1, 2002 at http://edexcellence.net/library/tsps/tsps.htm (14) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross Traub, James. “Better by Design? A Consumer’s Guide to Schoolwide Reform.” The Thomas B. Fordham Foundation (1999). December 1, 2002 at http://www.edexcellence.net/library/bbd/better_by_design.html Traub, James. “Success for Some.” The New York Times Education Life. November 10, 2002. Viadero, Debra. “As Levin Steps Back, Accelerated Schools Takes Stock.” Education Week on the Web. Vol. 19, number 7, page 5. December 4, 2002 at http://www.edweek.org/ew/ewstory.cfm?slug=07accel.h19 Viadero, Debra. “Study Shows Test Gains In 'Accelerated Schools'”. Education Week on the Web. January 9, 2002. Vol. 21, number 16, page 6. December 9, 2002 at http://www.edweek.org/ew/newstory.cfm?slug=16accel.h21 Viadero, Debra. “Who's In, Who's Out.” Education Week on the Web. January 20, 1999. Vol. 18, number 19, page 1, 12-13. December 2, 2002 at http://www.edweek.com/ew/vol18/19obey.h18 (15) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross 6. Appendix The Catalog of School Reform Models NW Regional Educational Laboratory NCCSR The National Clearinghouse for Comprehensive School Reform Accelerated Schools (K - 8) Accepted for Inclusion 2/1/98 | Re-accepted 11/1/01 | Description Updated 12/1/01 Type of Model Founder Current Service Provider Year Established # of Schools Served (9/1/01) Level Primary Goal Main Features Impact on Instruction Impact on Organization/Staffi ng Impact on Schedule Subject-Area Programs Provided by Developer Parental Involvement Technology Materials entire-school Henry Levin, Stanford University National Center for Accelerated Schools Project at the University of Connecticut, and various regional centers 1986 1,300 K-8 provide all students with enriched instruction based on entire school community’s vision of learning gifted-and-talented instruction for all students through "powerful learning" participatory process for whole-school transformation three guiding principles (unity of purpose, empowerment plus responsibility, and building on strengths) teachers adapt instructional practices usually reserved for gifted-and-talented children for all students governance structure that empowers the whole school community to make key decisions based on the Inquiry Process depends on collective decisions of staff no parent and community involvement is built into participatory governance structure depends on collective decisions of staff Accelerated Schools Resource Guide plus a field guide for each training component Origin/Scope The accelerated schools approach, developed by Henry Levin of Stanford University, was first implemented in 1986 in two San Francisco Bay Area elementary schools. The Accelerated Schools Project has now reached over 1,300 schools. General Approach Many schools serve students in at-risk situations by remediating them, which all too often involves less challenging curricula and lowered expectations. Accelerated schools take the opposite approach: they offer enriched curricula and instructional programs (the kind traditionally reserved for gifted-and-talented children) to all students. Members of the school community work together to (16) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross transform every classroom into a “powerful learning” environment, where students and teachers are encouraged to think creatively, explore their interests, and achieve at high levels. No single feature makes a school accelerated. Rather, each school community uses the accelerated schools process and philosophy to determine its own vision and collaboratively work to achieve its goals. The philosophy is based on three democratic principles: unity of purpose, empowerment coupled with responsibility, and building on strengths. Transformation into an accelerated school begins with the entire school community examining its present situation through a process called taking stock. The school community then forges a shared vision of what it wants the school to be. By comparing the vision to its present situation, the school community identifies priority challenge areas. Then it sets out to address those areas, working through an accelerated schools governance structure and analyzing problems through an Inquiry Process. The Inquiry Process is a systematic method that helps school communities clearly understand problems, find and implement solutions, and assess results. Results Two early small-scale evaluations yielded initial evidence of improved achievement, school climate, and parent and community involvement in accelerated schools. A 1993 evaluation comparing an accelerated school in Texas to a control school revealed that over a two-year period, fifth grade SRA scores in reading, language arts, and mathematics at the accelerated school climbed considerably. Over the same period, the scores of a control school declined (McCarthy & Still, 1993). In the other study, Metropolitan Achievement Test grade-equivalent reading scores at an accelerated school improved more than scores in a control school in four of five grades, although the results for language scores were mixed (Knight & Stallings, 1995). More recent studies involving larger numbers of elementary schools have also demonstrated gains for accelerated schools relative to comparison schools. In an independent study of eight different reform models in Memphis, the Accelerated Schools Project was one of three models that demonstrated statistically significant or nearly significant growth across all subjects on the TVAAS (Tennessee ValueAdded Assessment System) compared with control schools. In reading, the Accelerated Schools Project showed the highest gain of any model across the three years of the study (Ross, Wang, Sanders, Wright, & Stringfield, 1999). Unpublished data from 34 elementary schools in Ohio that implemented the Accelerated Schools Project in 1997 or before reveal that accelerated schools on average showed greater gains from 1997 to 1999 in fourth- and sixth-grade reading and mathematics on the Ohio Proficiency Test than the districts in which they were located. For schools starting their fifth year or beyond in 1997, the advantages were much larger. For example, 12% more students in these accelerated schools scored proficient or advanced on the sixth-grade reading test in 1999 than in 1997, compared to a 3% decline for district schools (Report for Ohio Center, 1999). Researchers from the Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation (MDRC) recently completed a five-year study of eight accelerated schools. They used third-grade reading and mathematics scores from the three years prior to implementation to predict what scores would have been during the following five years with no intervention. They then compared these predictions with actual scores to see if the accelerated schools approach had any impact. They found little or no impact on test scores during the first three years of implementation (when the focus was on reforming school structure and governance), then a gradual increase in scores during the fourth and fifth years (when substantial changes in curriculum and instruction were taking place). Average scores in the fifth year exceeded predicted scores by seven percentile points in reading and eight in mathematics, a statistically significant amount (Bloom et al., 2001). schools. To date, no studies have analyzed the impact of the Accelerated Schools Project on middle (17) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross Implementation Assistance Project Capacity: The National Center for the Accelerated Schools Project is located at the University of Connecticut. There are also 12 regional centers across the country based in universities and state departments of education. Across the national and regional centers, the Accelerated Schools Project employs 62 full-time and 27 part-time staff. Faculty Buy-In: 90% of the school community (all teaching and non-teaching staff plus a representative sample of other school community members including parents and district personnel) must agree to transform the school into an accelerated school. Students are also involved in age-appropriate discussions during the buy-in process. Initial Training: For each accelerated school, the National Center or a regional center trains a five-member team comprising the principal, a designated coach (often from the district office), a school staff member who will serve as an internal facilitator, and two other school staff members. Training for this team involves an intensive five-day summer workshop, two subsequent two-day sessions on Inquiry and Powerful Learning, and ongoing mentoring by a center staff member. The coach provides two days of training for the entire school staff just before the school year begins. Follow-Up Coaching: During the first year of implementation, the coach provides the equivalent of at least four additional days of training for all staff. Coaches also spend 25% of their time (generally at least one day per week) supporting the school. In the early stages, the coach is more of a trainer, introducing the process and guiding school community members through the first steps of implementation. In later stages, the coach helps schools evaluate how well the model is working, assists in overcoming challenges, and continually reinforces the accelerated schools philosophy to keep momentum alive. Additionally, an Accelerated Schools Project staff member visits the school three times. During the second and third years of implementation, the five-member school team receives a total of nine more days of training. Networking: The National Center and regional centers host an annual national conference and regional conferences, publish newsletters, support Web sites, and maintain a listserv connecting teachers, coaches, and centers via e-mail. Networking opportunities also enable accelerated school communities to interact with each other on a regular basis. Implementation Review: Continual self-evaluation is part of the process in accelerated schools. To help schools gather information, the National Center has developed a comprehensive assessment tool called The Tools for Assessing School Progress. Costs The Accelerated Schools Project (National Center and regional centers) charges approximately $45,000 per year for a Basic Partnership Agreement (minimum three-year commitment). This fee varies from state to state depending on subsidies and grants provided to the local regional center. The agreement includes, in the first year: training of a five-member team including the coach, the principal, and three school staff members (excluding travel expenses) training materials, including five copies of the Accelerated Schools Resource Guide three site visits by a project staff member technical assistance by phone, fax, and e-mail monthly networking opportunities year-end retreat a subscription to newsletters and the project's electronic network In addition, schools and/or districts must provide release time for the entire teaching staff for two days of initial training and the equivalent of four days of additional training during the first year. They must also schedule weekly meeting time amounting to about 36 hours per year and cover 25% of the full-time salary and benefits of the coach (estimated at $12,000-$20,000 for a coach external to the school). (18) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross Over the next two years schools receive targeted professional development in key components of the model, on-going technical assistance, monthly networking opportunities, and one site visit by a project staff member. Schools may contract with a center for additional site visits and other services as needed. State Standards and Accountability The Accelerated Schools Project empowers school communities to determine their own priorities for improvement. If the school community determines that aligning instruction with state standards and assessments is a priority area, then community members address that area by working through the accelerated schools governance structure and Inquiry Process. Student Populations As part of the catalog Web site search mechanism, each model had an opportunity to apply to be highlighted for its efforts in serving selected student populations. The five categories were urban, rural, high poverty, English language learners, and special education. To qualify for a category, a model had to demonstrate (a) that it included special training, materials, or components focusing on that student population, and (b) that it had been implemented in a substantial number of schools serving that population. The Accelerated Schools Project is highlighted in all five categories. It was designed primarily to serve schools with high proportions of students in at-risk situations. Hundreds of rural and urban schools with large concentrations of high poverty students have become accelerated schools. The model provides a process for addressing the unique needs of each school, often resulting in special efforts such as tutoring, after-school programs, or connections with social service organizations. Training includes strategies for instruction and curriculum development within the context of multicultural classrooms. The accelerated schools governance model joins special and regular education teachers together in teams, where they work toward the integration of special and regular education students. Special Considerations The accelerated schools process can be a challenging one. Teachers and administrators must be willing to relinquish hierarchical decision-making structures, work together, and expend considerable time and energy to transform a traditional school into an accelerated school. Founder Henry Levin estimates that this process can take three to five years. During this time, it is crucial to maintain regular meeting time and active coaching at the school site. Selected Evaluations Developer/Implementer Knight, S. L., & Stallings, J. A. (1995). The implementation of the accelerated school model in an urban elementary school. In R. L. Allington & S. A. Walmsley (Eds.), No quick fix: Rethinking literacy programs in America's elementary schools (pp. 236-251). New York: Teachers College Press. McCarthy, J., & Still, S. (1993). Hollibrook Accelerated Elementary School. In J. Murphy & P. Hallinger (Eds.), Restructuring schooling: Learning from ongoing efforts (pp. 63-83). Newbury Park, CA: Corwin. Segal, T. (1999). [Report for Ohio center]. Unpublished raw data. Independent Researchers Bloom, H. S., Ham, S., Melton, L., & O’Brien, J., with Doolittle, F. C., & Kagehiro, S. (2001). Evaluating the Accelerated Schools Approach: A look at early implementation and impacts on student achievement in eight elementary schools. New York: Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation. Ross, S. M., Wang, L. W., Sanders, W. L., Wright, S. P., & Stringfield, S. (1999). Two- and three-year achievement results on the Tennessee Value-Added Assessment System for restructuring schools in Memphis. Memphis: Center for Research in Educational Policy. (19) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross Core Knowledge (K - 8) Accepted for Inclusion 2/1/98 | Re-accepted 11/1/01 | Description Updated 8/1/02 Type of Model Founder Current Service Provider Year Established # of Schools Served (5/1/02) Level Primary Goal entire-school E. D. Hirsch, Jr. Core Knowledge Foundation 1986 600 K - 8 (a separate preschool program is available) to help students establish a strong foundation of vocabulary and skills to build knowledge and understanding Main Features sequential program of specific topics for each grade in all subjects structured program to build vocabulary and skills to improve literacy Impact on Instruction instructional methods to teach core topics are designed by individual teachers/schools; teachers are expected to teach all of the topics in the Core Knowledge Sequence at the specified grade levels Impact on full participation by all staff members is required Organization/Staffing Impact on Schedule common planning time is required; implementation requires full school participation for a minimum of three years Subject-Area yes, in all subjects Programs Provided by Developer Parental Involvement schools are expected to involve parents in planning and resource development Technology none required Materials detailed curricular materials provided and/or identified from other sources; schools are required to purchase specific textbooks, testing materials, and lesson plans Origin/Scope The Core Knowledge Foundation is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan organization founded in 1986 by E. D. Hirsch, Jr. The foundation’s essential program, a core curriculum entitled the Core Knowledge® Sequence, was first implemented in 1990. By May 2002, it was being used in over 600 schools. General Approach Core Knowledge focuses on teaching a common core of concepts, vocabulary, skills, and knowledge that characterize a “culturally literate” and educated individual. The purpose of the approach is to increase students’ receptive and productive vocabulary, increase comprehension, and help build a general knowledge base, thus increasing academic performance. Core Knowledge is based on the principle that the grasp of a specific and shared body of knowledge will help students establish strong foundations for higher levels of learning. Developed through research examining national and local core curricula and through consultation with education professionals in each subject area, the Core Knowledge Sequence provides a model of specific content guidelines for students in the preschool, elementary, and middle school grades. It offers a progression of detailed grade-by-grade topics in language arts, mathematics, science, history, geography, music, and (20) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross fine arts, so that students build on knowledge from pre-kindergarten through grade eight. Instructional strategies are modeled for teachers, but the selection of strategies is left to the discretion of teachers. The Core Knowledge Sequence typically comprises 50 percent of a school’s curriculum; the other 50 percent allows schools to meet state and local requirements not included in the Sequence. Schools are expected to incorporate structured, research-based reading and mathematics programs along with the Core Knowledge Sequence. The Sequence is detailed in the Core Knowledge Sequence Content Guidelines for Preschool through Grade Eight and illustrated in a series of books entitled What Your (First-, Second-, etc.) Grader Needs to Know. Parental involvement and consensus-building contribute to the success of the Core Knowledge Sequence. Parents are expected to be involved in obtaining resources, planning activities, and developing a schoolwide plan. The schoolwide plan aligns the Core Knowledge content with district and state requirements and assessments and includes strategies for successful implementation. Results A three-year study (1995-98) conducted by independent researchers at Johns Hopkins University compared student achievement at four Core Knowledge schools and four control schools (Stringfield, Datnow, Borman, & Rachuba, 1999). Researchers followed two cohorts of students in the schools, one from first to third grade, the other from third to fifth grade. They found that the Core Knowledge and control cohorts made similar gains in reading and mathematics on the CTBS and other norm-referenced tests. However, when Core Knowledge schools where less than 50 percent of teachers were implementing the sequence were excluded, the performance of the Core Knowledge students at the remaining schools was higher than that of control students in both subjects, particularly in the third-tofifth grade cohort. On tests created by the researchers specifically to measure achievement of Core Knowledge subjects, the Core Knowledge cohorts performed considerably better than control schools. Additionally, teachers at Core Knowledge schools reported that the model led to enhanced curricular coherence, increased teacher collaboration, and enriched classroom experiences for students. Another group of Johns Hopkins researchers examined implementation and student achievement from 1994 to 1999 at five Core Knowledge and five control schools in Maryland (Mac Iver, Stringfield, & McHugh, 2000). Problems in continuity of the sample prevented the researchers from calculating average five-year gains. They did calculate three-year gains, reporting that the first-to-third grade cohort at control schools gained 6.4 NCEs on the CTBS reading comprehension subtest, compared with 4.8 NCEs at Core Knowledge schools. However, when the lowest implementing Core Knowledge school was excluded from the analysis, the Core Knowledge cohort at the remaining four schools outgained their control school counterparts (8.1 versus 4.2 NCEs). A district official in Oklahoma City, where over 30 elementary schools have implemented the Core Knowledge curriculum, wrote a dissertation examining the academic achievement of Core Knowledge students (Taylor, 2000). The author compared ITBS scores of third-, fourth-, and fifth-grade students in 29 Core Knowledge classrooms across the district (classrooms where teachers were deemed to be fully implementing the model) to scores of non-Core Knowledge students who were matched on six variables: grade, pre-test score, gender, ethnicity, free lunch eligibility, and special education eligibility. From 1998 to 1999, the Core Knowledge students outscored the control students on seven of eight subtests, with statistically significant advantages in reading comprehension, reading vocabulary, and social studies. The author also examined fifth-grade scores in reading and social studies on the 2000 Oklahoma CriterionReferenced Text for a smaller set of students. She found statistically significant advantages for the Core Knowledge students on three of four reading objectives and six of eight social studies objectives, with large effect sizes (0.5 or higher) in many cases. Additional studies have demonstrated promising trends in test scores at a variety of Core Knowledge schools. For example, at Hawthorne Elementary School in Texas, an inner-city school with a large Hispanic population and a 96 percent free/reduced-price lunch rate, a district evaluator examined 1994 and 1995 Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAAS) scores for grades three through five (Schubnell, 1996). She found that fifth-graders scored considerably higher than third-graders in reading (21) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross and mathematics in both years, suggesting a cumulative effect for the program. Also, Hawthorne fourthgraders who took the test in 1994 and again as fifth-graders in 1995 showed a gain of 4.8 Texas Learning Index units in reading, compared to a 0.7 unit gain districtwide. There were no significant differences in mathematics scores. Implementation Assistance Project Capacity: The Core Knowledge foundation is headquartered in Charlottesville, Virginia. There are cadres of trainers in Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. Training is provided at the school site. Faculty Buy-In: The school or school district must obtain the commitment of at least 80 percent of the teachers who will be involved in the implementation. Implementation requires full school participation for a minimum of three years. Teachers are expected to teach all of the topics in the Core Knowledge Sequence at the specified grade levels. Initial Training: Initial training involves five days (which may be consecutive or not) of intensive on-site training for all teachers and administrators. The training includes an overview of Core Knowledge; development of a schoolwide plan; alignment of Core Knowledge topics with state and district standards and assessments; advice on obtaining resources and parent involvement; and lesson planning. In addition, a two-day Core Knowledge Leadership training is required for principals and school-based Core Coordinators. Follow-Up Coaching: Two days of follow-up training are provided for Core Coordinators in coaching, observing, and providing feedback. Three two-day follow-up visits conducted by Core Knowledge consultants are required each year for CSRD schools during their first three years of implementation. In addition, a variety of workshops to assist with implementation analysis are offered. Also available are summer workshops that focus on collaborative planning, lessonwriting, and integrating the Core Knowledge Sequence with local curricular guidelines. Networking: Core Knowledge supports a Web site, publishes a quarterly newsletter, and hosts a national conference each spring. Implementation Review: After receiving documentation that includes a copy of the school’s yearlong plan, sample lesson plans, and a letter of commitment from the school indicating the Core Knowledge Sequence is being implemented by at least 80 percent of the teaching staff, the school is recognized as an official Core Knowledge school. Costs Schools are required to commit to the implementation of Core Knowledge for a minimum of three years. The cost is determined by the number of staff members and students. For a school with 25 teachers and 500 students, estimated costs would be $36,000 for year one, $32,000 for year two, and $32,000 for year three. These fees cover the following services and materials: Leadership training for the principal and Core Knowledge coordinator (two days per year) Professional development training conducted on-site by Core Knowledge consultants (five days per year) Site visits by Core Knowledge consultants (three two-day visits per year) School Kit Core Knowledge training materials for teachers (new materials each year) In addition to the estimated costs, schools are required to: Purchase the Pearson Learning/Core Knowledge history and geography textbooks (grades K-6); Allocate a minimum of $1,000 per teacher for Core Knowledge-related materials per year; Allocate a minimum of $8 per student in grades 1-5 for administration and scoring of TASA’s Core Knowledge Curriculum Referenced Tests; and Purchase the Baltimore Curriculum Project lesson plans. State Standards and Accountability On-site training includes assistance in helping teachers review and align state standards and assessments with the topics included in the Core Knowledge Sequence. A yearlong plan is developed that (22) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross organizes the state standards and content into the months of the year. This ensures that content and skills are taught prior to testing, and it creates a pacing structure that helps in planning lessons. Sample state alignments for various states are posted on the Core Knowledge Web site. Student Populations As part of the catalog Web site search mechanism, each model had an opportunity to apply to be highlighted for its efforts in serving selected student populations. The five categories were urban, rural, high poverty, English language learners, and special education. To qualify for a category, a model had to demonstrate (a) that it included special training, materials, or components focusing on that student population, and (b) that it had been implemented in a substantial number of schools serving that population. Core Knowledge did not apply to be highlighted in any categories. However, it has been implemented across the U.S. in a wide variety of urban and rural settings with diverse student populations. Special Considerations Teachers must be willing to implement the Core Knowledge Sequence for three years and to develop and implement a sequential program of skills instruction in the areas of reading and mathematics. The school must develop a schoolwide planning document that contains the Core Knowledge topics and district/state standards. Selected Evaluations Developer/Implementer Taylor, G. L. (2000). Core Knowledge: Its impact on the curricular and instructional practices of teachers and on student learning in an urban school district. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Nova Southeastern University. Independent Researchers Mac Iver, M. A., Stringfield, S., & McHugh, B. (2000). Core Knowledge curriculum: Five-year analysis of implementation and effects in five Maryland schools. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, Center for Research on the Education of Students Placed At Risk (CRESPAR). Schubnell, G. (1996). Hawthorne Elementary School: The evaluator’s perspective. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 1(1), 33-40. Stringfield, S., Datnow, A., Borman, G., & Rachuba, L. (1999). National evaluation of Core Knowledge sequence implementation: Final report. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, Center for Social Organization of Schools. (23) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross Core Knowledge at a Glance: Major Topic Headings, 6-8 ©1999 Core Knowledge® Foundation. Sixth Grade Seventh Grade Eighth Grade I. Writing, Grammar, and Usage I. Writing, Grammar and Usage II. Poetry II. Poetry III. Fiction and Drama (Stories; III. Fiction, Nonfiction, and Drama III. Fiction, Nonfiction, and Drama Shakespeare; Classical Myths) IV. Foreign Phrases Commonly Used IV. Foreign Phrases Commonly IV. Sayings and Phrases in English Used in English History and World World World Geography I. World Geography (Spatial Sense; I. America Becomes a World Power I. Decline of European Colonialism Deserts) II. World War I, “The Great War” II. Cold War II. Lasting Ideas from Ancient III. Russian Revolution III. Civil Rights Movement Civilizations (Judaism, Christianity; IV. America from the Twenties to IV. Vietnam War and the Rose of Greece and Rome) the New Deal Social Activism III. Enlightenment V. World War II V. Middle East and Oil Politics IV. French Revolution VI. Geography of the United States VI. End of the Cold War: V. Romanticism Expansion of Democracy and VI. Industrialism, Capitalism, and Continuing Challenges Socialism VII. Civics: The Constitution – VI. Latin American Independence Principles and Structure of Movements American Democracy American VIII. Geography of Canada and Mexico I. Immigration, Industrialization, and Urbanization II. Reform Visual Arts I. Art History: Periods and Schools I. Art History: Periods and Schools I. Art History: Periods and Schools (Classical; Gothic; Renaissance; (Impressionism; Post(Painting Since World War II; Baroque; Rococo; Neoclassical; Impressionism; Expressionism and Photography; 20th-Century Romantic; Realism) Abstraction; Modern American Sculpture) Painting) II. Architecture Since the Industrial Revolution Music I. Elements of Music I. Elements of Music I. Elements of Music II. Classical Music: From Baroque to II. Classical Music (Romantics and II. Non-Western Music Romantic (Bach, Handel, Haydn, Nationalists (Brahms, Berlioz, Liszt, III. Classical Music: Nationalists Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Wagner, Dvorak, Grieg, and Moderns (Sibelius, Bartok, Chopin, Schumann) Tchaikovsky) Rodrigo, Copland, Debussy, III. American Musical Traditions Stravinsky) (Blues and Jazz) IV. Vocal Music (Opera; American Musical Theater) Mathematics I. Numbers and Number Sense I. Pre-Algebra (Properties of the I. Algebra (Properties of the Real Real Numbers; Polynomial Numbers; Relations, Functions, II. Ratio and Percent Arithmetic; Equivalent Equations and Graphs; Linear Equations and III. Computation and Inequalities; Integer Functions; Arithmetic of Rational IV. Measurement Exponents) Expression; Quadratic Equations V. Geometry and Functions) II. Geometry (Three-Dimensional VI. Probability and Statistics Objects; Angle Pairs; Triangles; II. Geometry (Analytic Geometry; VII. Pre-Algebra Measurement) Introduction to Trigonometry; Triangles and Proofs) III. Probability and Statistics Science I. Plate Tectonics I. Atomic Structure I. Physics II. Oceans II. Chemical Bonds and Reactions II. Electricity and Magnetism III. Astronomy: Gravity, Stars, and III. Cell Division and Genetics III. Electromagnetic Radiation and Galaxies Light IV. History of the Earth and Life IV. Energy, Heat, and Energy Forms IV. Sound Waves Transfer V. Evolution V. Chemistry of Food and V. Human Body (Lymphatic an Respiration VI. Science Biographies Immune Systems) VI. Science Biographies VI. Science Biographies Language I. Writing, Grammar, and Usage Art/English II. Poetry (24) L. Bailey Fall 2002 EDU 35 Prof. Ross (25)