“Women and the Great Depression” by Susan

advertisement

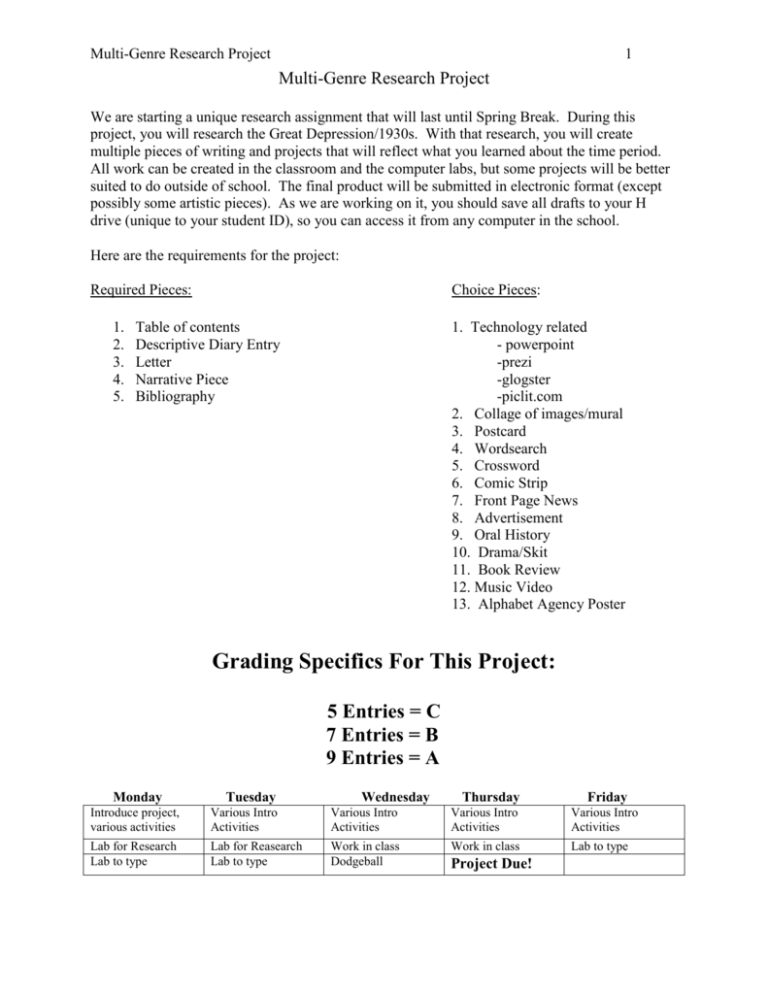

Multi-Genre Research Project 1 Multi-Genre Research Project We are starting a unique research assignment that will last until Spring Break. During this project, you will research the Great Depression/1930s. With that research, you will create multiple pieces of writing and projects that will reflect what you learned about the time period. All work can be created in the classroom and the computer labs, but some projects will be better suited to do outside of school. The final product will be submitted in electronic format (except possibly some artistic pieces). As we are working on it, you should save all drafts to your H drive (unique to your student ID), so you can access it from any computer in the school. Here are the requirements for the project: Required Pieces: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Choice Pieces: Table of contents Descriptive Diary Entry Letter Narrative Piece Bibliography 1. Technology related - powerpoint -prezi -glogster -piclit.com 2. Collage of images/mural 3. Postcard 4. Wordsearch 5. Crossword 6. Comic Strip 7. Front Page News 8. Advertisement 9. Oral History 10. Drama/Skit 11. Book Review 12. Music Video 13. Alphabet Agency Poster Grading Specifics For This Project: 5 Entries = C 7 Entries = B 9 Entries = A Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Introduce project, various activities Various Intro Activities Various Intro Activities Various Intro Activities Various Intro Activities Lab for Research Lab to type Lab for Reasearch Lab to type Work in class Dodgeball Work in class Lab to type Project Due! Multi-Genre Research Project 2 Required Pieces 1. Table of Contents Make a typed list of all parts in the project. This is your first page and should have your name. 2. Descriptive Diary Entry Create entries in the diary of a teenager living in the Depression. As this teenager, you are part of an extended family living in Oklahoma (be specific what part of the state you choose to be from). Your family includes one grandparent, two parents, three children – yourself at whatever age you really are, one sibling that is 10 or younger, and one sibling that is 19 or older. You must have 5 entries. They must be in chronological order and seem as if you really lived in the 1930s. Consider including the following topics: hardships endured by families during the Great Depression, effect of the Depression on rural areas, support or opposition to the election of FDR, changes in the way people lived during the Depression, what life was like for a teenager during these years. 3. Letter: In friendly letter format, write a letter “back home” to the family you left behind when you hopped a train and headed off to new adventures. 4. Narrative Piece: Find at least one photograph (online) of a person or scene from the Great Depression. You will write a story based on the photograph (s). Story should have plot, setting, theme, character, a conflict that is resolved, and should be told from either first or third person point of view. Include the photo with the story. Aim for 500-1000 words. 5. Bibliography: This page will be the last page of your project and it will have all sources you used for information including photographs. It must be in MLA format. Multi-Genre Research Project 3 Choice Pieces 1. Technology Choose one of the following as a presentation tool to explain what you have learned about the Great Depression Powerpoint- In a minimum of 5 slides, share what you learned in your research. Pictures are encouraged! Prezi- Using the website www.prezi.com, create a presentation that can be shared with the class. Piclit- Using www.piclits.com, create unique picture/writing/illustrating of a theme of the 1930s. You must have email to create an account. If you have another way to use technology and accomplish the same purpose, please ask permission before proceeding. 2. Collage of images/mural Create a collage of photos or draw/paint a mural that depicts life in the 1930’s. Can use any medium. Pictures can be printed from the internet. Collage or mural should be on a half sheet of poster board or a piece of 11 x 17 paper. See me for the paper. You are free to use bigger paper, but you will need to get your own. Freezer paper works well for really big murals. Your collage or mural should have a theme ( for example “women in the Depression” or “children in the Depression” or “jobs in the depression” ) or should focus on a particular place. A mural might also depict a progression of time, like a family moving from Oklahoma to California or a family who loses its income and becomes dependent on others. 3. Postcard In the style of a traditional postcard, write a brief message to a family member back home, telling him/her about your adventures. Design a stamp and make up an address for the recipient. On the front of a piece of typing paper, either draw a picture or print and paste a picture that would be fitting for a postcard. Remember most postcards are pictures of places. To get ideas, just google 1930’s postcards. Stamp Name of recipient Address of recipient Multi-Genre Research Project 4 4. Word Search Use a website like www.puzzlemaker.com to create a word search with a minimum of 20 terms related to the Great Depression and the 1930s. You do not have to provide the key. 5. Crossword Use a website like www.puzzlemaker.com to create a crossword puzzle with a minimum of 25 clues about the Great Depression and the 1930s. You do not have to provide the key. 6. Comic Strip Using the format of a traditional newspaper comic strip, design one with a minimum of 5 boxes, telling a story or revealing a theme of the time period we are studying. Keep in mind details like authentic speech and dialect. 7. Front page News Create the front page of a 1929 or 1930’s newspaper. You will need to include the following: Title of Newspaper, city, and date At least 1 short article that deals with the depression on a local level (for example, a company laying off workers or problems with transients) – must have headline and a quote from an imaginary local person At least 1 short article that deals with the depression on a national level ( for example, the election of FDR or the stockmarket crash) - must have headline and quote or statistic from one of your research articles At least 1 photograph (find this online) You can do this digitaly or literally type and print your pieces and glue them to a big 11 x 17 page. 8. Advertisement Create an ad for a newspaper or magazine. It should promote a product sold in the 1930’s. This can be done on typing paper and be done by hand or can be digitial. It should have the following: Name of product What the product does Manufacturer Price Where to buy it Illustration Multi-Genre Research Project 5 9. Oral History You will interview a relative, family friend, or anyone you know who grew up in the 1930’s. You can either tape/video the interview or take good notes. Tips: Have at least 20 questions prepared before the interview. It is okay if you think up more during the interview. Don’t interrupt; be polite and remember that elderly people sometimes talk slowly. Ask open-ended questions and allow the person to think before responding. For example, don’t ask “Do you remember FDR?” Instead ask, “What did your family think of FDR?” Your interview may have to take place in multiple sessions if the person is ill or becomes tired. After the interview, you will write a short biography about what this person’s life during the depression. Be sure to explain who you interviewed in the introduction. It may be more in essay form or more in narrative form, depending on the types of questions/answers you had. You will also turn in a list of the questions you used. 10. Drama/Skit: This can be done individualy, but you may need to enlist some helpers for this. You will write and act out a skit/drama. It may be filmed and burned to a DVD outside of school OR you may perform it before the class. Must turn in written script Can be a monologue or have multiple characters. It should be at least 5 minutes long. No more than 15 mintues. Suggested topics: life in a Hooverville, workers being laid off, a family being evicted, a family in the dust bowl, life on the road for a migrant Consider the following info when writing: Setting Characters Conflict Will you use any factual info? How has the depression affected your characters? Does your dialogue show the emotions of the characters? Do you need props/costumes? Do you need a background? What message do you want the audience to walk away with? Multi-Genre Research Project 6 11. Book Review Choose one of the books from the list below to use in a book review OR bring a different one to me for approval. Book review should be in essay form and include the following: Author, Title, Number of pages A summary of the book Your reactions to the book (what you liked/did not like, would you recommend it) Lessons you learned about what life was like during the Great Depression and the causes/effects of the Great Depression Should be approx. 300 words Possible Books: A Long Way from Chicago: A Novel in Stories by Richard Peck Christmas After All: the Great Depression Diary of Minnie Switft by Kathryn Lasky Survival in the Storm: the Dust Bowl Diary of Grace Edwards by Katelan Janke The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck Out of the Dust by Karen Hess 12. Music Video Student should read labor songs from the 1920s and 1930s as research. Suggestions are music from Pete Seeger and Bob Reiser’s Carry It On! (1985), Edith Fowke and Joe Glazer’s Songs of Work and Freedom (1973), or look for something from Woody Guthrie. There are also good options in Jazz and Blues from the late 1920s and into the 1930s. After you researched songs, select at least two. Record yourself performing one song as it is originally written. Re-write the second song and give it a modern feel by making it about issues for workers today. You could even give it a updated feeling by making it rap, country, etc. Record this song also. You will submit the recordings and a set of lyrics for both songs. Be sure to include original authors and dates. ** 13. Alphabet Agency Poster Create a poster that advertises one of the agencies created under FDR’s New Deal. Some of those agencies are TVA, CCC, NRA (National Recovery Admin.), AAA (Agricultural Adjustment Act) and WPA. Do on a sheet of typing paper. The poster should advertise the agency and what it’s purpose was. Needs an illustration, not just words. Can be done by hand or digitally. Include a paragraph of approx. 100 words that describes what this agency did to help people and the country during the Great Depression Multi-Genre Research Project 7 Suggested Websites (look for sites ending in .gov, .org, .edu) http://www.ushistory.org/us/48a.asp Factual information about The Great Depression http://www.ushistory.org/us//49.asp Factual information about The New Deal http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/depression/depression.htm Factual information including phots about the Great Depression, Dust Bowl and Recovery Efforts http://www.erroluys.com/frontpage.htm Read articles on the survival of teenage hobos written by author Errol Lincoln Uys of Riding the Rails. http://www.monh.org/Default.aspx?tabid=405 "Teenage Hoboes in the Great Depression." Listen to oral histories and view images of former transients from the National Heritage Museum's online exhibition. http://www.livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe30s/water_07.html Listen to an interview with Walter Ballard, a former teenage hobo who left his impoverished family to find work in the Great Plains. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/fsahtml/fadocamer.html "Documenting America." A photographic series from the Library of Congress featuring iconic photos of migrant workers, farmers, and cities during the Great Depression (from “Errol Lincoln Uys: a writer’s website” http://erroluys.com) “From Then on I Was a Loner” by Gene Wadsworth, Sequim, Washington When Gene Wadsworth caught his first freight at age 17 on a winter's night in 1932, he'd never ridden on a train before. Orphaned at age 11, Gene was living at Burley, Idaho, with an uncle who had five children of his own. "Why do you hang around here, when you're not wanted?" one of his cousins asked him. That night, Gene stuffed his few belongings into a flour sack and hit the road. "I was about as low as a kid could get, as I walked over the Snake River Bridge. I was thinking of suicide, looking down into that black water, but I kept walking. A freight train was just pulling out of a little town. I stopped to let it pass. "I'll never know why I reached out and grabbed the rung of the boxcar ladder. I climbed to the catwalk. I Multi-Genre Research Project 8 lay on my stomach and hung on for dear life, as we rumbled off into the night. I was scared stiff." Taking the advice of older hoboes, Gene headed south to warmer climes and transient camps established by the government, where he could get work at $1 a week, plus food and shelter. Moving between camps in California and Arizona, he made friends with a young man in the same position. "Jim was also blond, my age and size - six feet and 165 pounds. Everyone believed we were brothers. We thought a lot alike and hit it off very good. We teamed up and decided to make our fortune together. "All went well with us, until one night when Jim and I were riding on the ladders between two boxcars. "It was so cold my hands nearly froze. I slipped my arm over a rung of the ladder and put my hand in my jacket pocket. Being back to back, I couldn't see Jim. "All of a sudden the train gave a jerk, as it took up slack in the draw bars. "I heard Jim let out a muffled moan, as he fell. I whirled round and made a grab for him. He had on a knit cap. I got the cap and a handful of blond hair. Jim was gone. Disappeared under the wheels. "No way could Jim survive. I got so sick I'd to climb up and lie on the catwalk. "From then on, I was a loner. I never teamed up with anyone, but always traveled alone." (from “Errol Lincoln Uys: a writer’s website” http://erroluys.com) “Was I Leaving Little for Nothing?” By Leslie E. Paul, Seattle, Washington Leslie E. Paul's vivid memories of leaving home in the summer of 1933 begin on the back porch of his house in Duluth. He was 18 years old, newly graduated from high school, the son and stepson of railroad men. "I stepped off the porch and turned right. My eyes searched for the one-armed railroad dick, who'd threatened to arrest me the next time I trespassed on railroad property. I was relieved when I didn't see him. "I stepped from tie to tie, past the cinder pit and around the turntable. High school had been out a week, but I recognized a string of boxcars that had been there for days. I walked past the last boxcar, Multi-Genre Research Project 9 one hundred yards on to a pile of switch ties that stood parallel to the tracks. Each day for two weeks, going to school and coming home, I'd wondered what was in the bundle lying on the pile. "I picked it up and unfolded it. It was a blanket sewn together to make a sleeping bag. A hobo had dropped it there. "I knew then what I must do. It was the Depression; there was no work. I was a burden to Mother and Gus, my step-father. I took the blanket and hurried home. I said nothing to Mother then, only that I was going down to Scott's to get a flat fifty box of cigarettes. Ordinarily I was reluctant to add to the delinquent account; today I found abundant courage. Besides the tin of cigarettes, I asked for two sacks of Golden Grain. 'Charge it,' I said. Scott looked taken aback but said nothing. "I returned home and told Mother I was leaving. She didn't fight it, but she was sad. Mother owned no suitcase or tote. All she had was a black satin bag, the size of a pillow case. I jammed my new sleeping bag inside it, three or four pairs of socks, shorts, an old sweater, the cigarettes and sacks of Golden Grain. "Mother made two sandwiches. She went to her purse and gave me all the money she had: 72 cents. "I gave Mother a big kiss and a long, tight hug. She said nothing, but the tears streamed down her face. I turned and left, the black satin bag over my shoulder. Had I been brave enough, I would've been coward enough to go back. "I stopped at the roundhouse and found Gus working on one of the engines. Gus hadn't really been a father, but I owed him a lot. I had a roof over my head and there was always something to eat. I shook his hand and said goodbye. "The freight yard was a terminal for trains going to Canada. My best bet was to go to Carleton, 19 miles away. The easiest way to get there was to walk. "I crossed the tracks, climbed the fence and started up the hill to the highway. I turned around at the top. The tears came then, and one sob. The second one I swallowed. Every boy becomes a man, some younger, some older. I was eighteen and one week. Was I leaving little for nothing?" “Added Obstacles for African Americans” Multi-Genre Research Project 10 (From the website The American Experience - Website ©1996-2010 WGBH Educational Foundation. This site is produced for PBS by WGBH. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/rails-added-obstacles/) Clarence Lee was 16 in 1929 when his father informed him that he would have to leave home. Times were tough and there was only so much food to go around. "Go fend for yourself," Lee's father instructed him. "I cannot afford to have you around any longer." Lee reluctantly hopped a freight car out of Louisiana in hopes of realizing better days. What he found instead was the prevailing loneliness of hobo life: wandering from place to place looking for work, food, and shelter. Added to his plight was the fact that Lee's skin color made him suspect in the eyes of many of the folks he met along the road. He recalled how white hobos were treated differently than African American hobos when it came to soliciting the kindness of strangers. "White kids, they fared better. They might let them stay in a house with them, but me, I could sleep in a barn with the mules and the hay." While tales of friendships among hobos that transcended race abound, many African American hobos recounted being made to feel like outcasts among outcasts. Harold Jeffries of Chicago recalls how he first felt the sting of racism when he and six buddies took to the tracks out of Minneapolis in 1935: "As black kids from the north, we'd heard of racial discrimination, but not one of us had actual experience of harsh prejudice. Our first frightening encounter came at the Union Pacific roundhouse in Kansas City. Some of the kids drank from a 'whites only' fountain. We were literally run out of the U.P. yards. We walked across the long bridge from the Kansas side of the city over to Missouri to see a girl I'd met back home. We told her family what had happened in the U.P. yards. They sat us down and gave us a lecture about the ways of the South." Sadly, one of the "ways of the South" was the brutal practice of lynching. As the Great Depression rocked the economies of every state in the Union, jobs were scarce. Among African Americans, unemployment reached a staggering fifty percent. Even so-called menial jobs were now eagerly sought after. In many cities, whites demanded that they be given first crack at any job openings by virtue of their skin color. Some went so far as to revive lynchings as a way of intimidating employers and African Americans looking for work. The New Republic, reporting on the increase in the number of lynchings in the South, observed that "dead men not only tell no tales but create vacancies." Lynchings were also used to enforce mob justice. An African American hobo had to be Multi-Genre Research Project 11 aware of the racial climate in the towns he was traveling through. Sometimes, they were tipped off. Clarence Lee recalls: "I was leavin' from Baton Rouge to go to Denham Springs, Louisiana, and this man made one stop in between. He had a small station place and somebody got on the train and was talking to the conductor and he says, 'Well, that boy has to be put off here. They're going to lynch him. See, there has been a rape between here and Denham Springs, and he fits the description.' So he put me off right in the middle of a swamp. Probably saved my life." Through his fiction, esteemed author Ralph Ellison recounted his experiences as an African American riding the rails. In 1933, Ellison earned a scholarship to the Tuskegee Institute to study music. Because he could not afford train fare to make the journey from his home in Oklahoma City to Alabama, he resorted to hopping freights. In his short story, "I Did Not Learn Their Names," he writes of confronting fellow hobos whose bigoted attitudes where passed down to them from their elders. "I was having a hard time trying not to hate in those days, and I felt bad whenever I found myself in a position that might have been interpreted that way. But I had learned not to attack those who were not personally aggressive and who only expressed passively what they had been taught." Still, Ellison's acquiescence would only go so far. As a fellow traveler among the wandering and the wounded, he refused to quietly take his "place." He wrote, "I had learned that on the road you really had no 'place'; you were all the same though some of them did not understand that." For many hobos, however, life on the road -- and often on the run -- engendered a greater understanding of the plight of African Americans and others looked down upon by certain sectors of society. "Steam Train" Maury Graham, who began his hoboing days in 1931 when he was fourteen, points out that "having experienced the intolerance of those who despised hobos, the 'bo tended to make the acceptance of others -- no matter what their color -- a legacy that they hoped would be passed on to everyone." Multi-Genre Research Project 12 “Women and the Great Depression” by Susan Ware ( from The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/great-dpression/essays/women-and-great-depression ) In 1933 Eleanor Roosevelt’s It’s Up to the Women exhorted American women to help pull the country through its current economic crisis, the gravest it had ever faced: “The women know that life must go on and that the needs of life must be met and it is their courage and determination which, time and again, have pulled us through worse crises than the present one.” While women as a group could not end the Depression (mobilization for World War II deserves that credit), the country could never have survived the crisis without women’s contributions. “We didn’t go hungry, but we lived lean.” That expression sums up the experiences of many American families during the 1930s: they avoided stark deprivation but still struggled to get by. The typical woman in the 1930s had a husband who was still employed, although he had probably taken a pay cut to keep his job; if the man lost his job, the family often had enough resources to survive without going on relief or losing all its possessions. Still, Eleanor Roosevelt noted, “Practically every woman, whether she is rich or poor, is facing today a reduction of income.” In 1935–1936 the median family income was $1160, which translated into $20–25 a week to cover all their expenses, including food, shelter, clothing, and perhaps an occasional treat like going to the movies. Women “made do” by substituting their own labor for something that previously had been bought with cash or by practicing petty economies like buying day-old bread or warming several dishes in the oven to save gas. Living so close to the edge, women prayed that no catastrophic accident or illness would swamp their tight budgets. “We had no choice,” remembered one housewife. “We just did what had to be done one day at a time.” In many ways men and women experienced the Depression differently. Men were socialized to think of themselves as breadwinners; when they lost their jobs or saw their incomes reduced, they felt like failures because they couldn’t take care of their families. Women, on the other hand, saw their roles in the household enhanced as they juggled to make ends meet. Sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd noticed this trend in a study of Muncie, Indiana, published in 1937: “The men, cut adrift from their usual routine, lost much of their sense of time and dawdled helplessly and dully about the streets; while in the homes the women’s world remained largely intact and the round of cooking, Multi-Genre Research Project 13 housecleaning, and mending became if anything more absorbing.” To put it another way, no housewife lost her job in the Depression.