“Amputation in Civil War Necessary to Save Lives”

advertisement

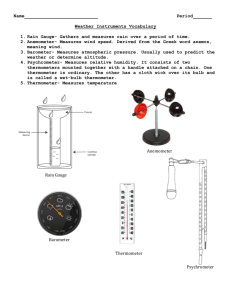

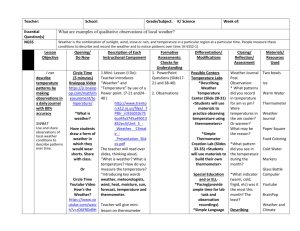

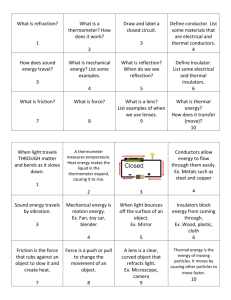

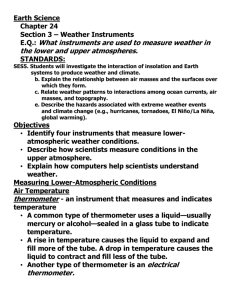

“Thermometer’s Acceptance Increased Slowly” Snakeroot Extract, Number 22, December 1991 Unstandardized scales, inadequate control of fluid and the lack of sophistication delayed the widespread acceptance of the thermometer as a valuable diagnostic instrument. In the 1600s, physicians became interested in those physiologic conditions under which body temperature should change. As a result, physicians began to explore the possibilities of recording temperature by transferring a patient’s body heat to a glass tube. Santorio Santorio, an Italian professor of medicine at Padua, demonstrated to his students such a device in the early 1600s. The instrument consisted of a glass tube, the bulb of which the patient inserted into the mouth. The physician placed the tube’s open end into a liquid-filled vessel and measured the patient’s temperature by observing the change in the instrument’s reading during ten beats of the pulsilogium, or small pendulum. The three types of thermometers introduced during the 1600s differed in their fluid content, which consisted of either air, spirit or alcohol, or mercury. Many thermometers were coiled of curved in nature until physicians realized that air responds as quickly to pressure as to heat. Besides the problems with their shapes, the tubes for spirit-or-mercury-based thermometers also proved inadequate to control the even expansion those fluids undergo when heated. As a result, the mercury-based instruments were abandoned until a smaller, more uniform bore could be made in the thermometer’s tube. During the late 1600s and early 1700s, thermometers still lacked universal scales and, therefore, physicians continued their practice of comparing the patient’s temperature to the temperature of the person taking the measurements. However, the development of standardized temperature scales by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit and Anders Celsius in the 1700s enabled physicians to determine the average body temperature with either scale. The uniform expansion of mercury prompted its reintroduction commercially as the preferred liquid for thermometers in 1822, when a method was developed to produce the uniform bore needed for the thermometer’s tube. Fascinated by the ability of a small amount of air to move mercury within a tube, John Phillips, a professor of geology at Oxford University, England, designed the self-registering thermometer in 1832. This type of thermometer, sometimes produced with a length as large as ten inches, contained a half-inch portion of mercury, called an index, which remained separated from the column of mercury by an air space. Although the mercury column receded after thermometer was removed from the patient, the index remained at the registered temperature until the physician shook the thermometer. Despite these advances, physicians did not incorporate the thermometer into the spectrum of their diagnostic equipment as quickly as the stethoscope or microscope. In 1866, F.W. Gibson noted this discrepancy when he wrote, “[T]he day is not, I think, very far distant when the physician will consider the thermometer not less indispensable to him that the stethoscope and microscope, and when the surgeon will not neglect the observation of the temperature.” During the mid-1800s, though, the thermometer continued to lack appeal because the instrument did not directly contribute to the prevailing diagnostic patterns. Physicians during this time began to consider alterations of body structure and function as the ultimate foci of disease and desired elaborate instruments and laboratory tests to uncover these alterations. These specialized tools contrasted greatly with the thermometer, which measures a general phenomenon such as body temperature. Coupled with problems of calibration and breakage, this factor relegated the thermometer to its use in hospitals, where attendants could regularly measure the patients’ temperatures. However, research-based physicians embraced the thermometer as another instrument capable of providing objective measurements. In 1868, German physician Carl Wunderlich published his monograph in which he examined the relationship between changes in body temperature and the courses a number of diseases followed. Inspired by Wunderlich, Edouard Seguin, a French-born physician who came to America in 1848, continued his mentor’s efforts to educate physicians about the value of the thermometer in medical diagnosis. By the 1880s, most physicians recognized the value of measuring body temperatures and the maximum opportunities the thermometer offered for use in preventative disease programs. In describing the thermometer’s impact on medical diagnosis, Charles Wilson Ingraham in 1895 reflected that, “Though the thermometer is but a piece of glass containing mercury, yet it diffuses information that sways the opinions of physicians in council….We cannot but wonder how our ancestors could have intelligently practiced medicine and surgery without the aid of the thermometer.” Sources: Medicine and Its Technology: An Introduction to the History of Medical Instrumentation (1981) by Audrey B. Davis, and Medicine: An Illustrated History (1978) by Albert S. Lyons, M.D., and R. Joseph Petrucelli, II, M.D.