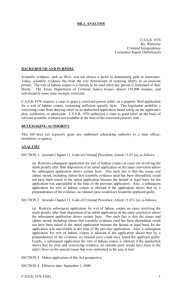

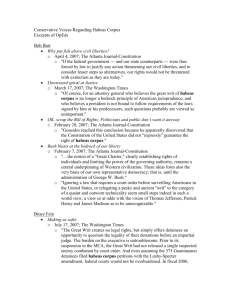

Habeas_corpus_and_impressment_1700-1816_(1)

advertisement