Trans-Generational Justice – Compensatory vs

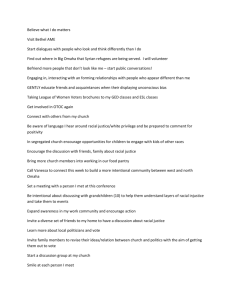

advertisement