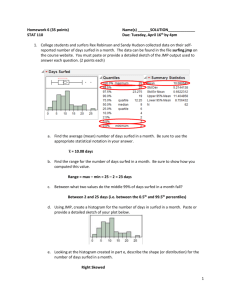

STAT 101, Module 1: Introduction

advertisement

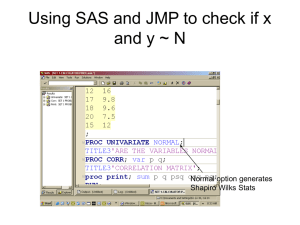

STAT 101, Module 1: Introduction, Data Exploration What is Statistics? Statistics, the discipline, is the art and science of extracting useful information from data. Homonym: What is a statistic? A number calculated from data. Examples: means, medians, ranges,… Why Statistics? Some problems you might face: What am I going to do with these numbers? You are on your new job. Your new boss is testing the waters with you, saying "Here is data for 10 stocks we've been interested in lately; have a look at them and let me know what you find." Now what? What are the odds? My colleague is pricing an option, and he needs an estimate of the probability of a market drop of more than 10%. What's the future? My business has monthly demand data for the last 5 years. Forecast next month's demand. How accurate are my numbers? I just produced a forecast for next month's demand. How accurate could it possibly be? Am I a sucker to chance? I have to compare the performance of two call centers. I find differences in the data from the two centers, obviously, but how do I know that they are not simple flukes? Key Issues: Data (finding, collecting, organizing) Data Analysis (graphing, higher “bean counting”) Discovery of information in data (detective work) Uncertainty in analysis (getting the gamble right) Communication of insights (good writing) Techniques: Graphical summaries of data (good pictures) Numeric summaries of data (“bean counting”) Statistical models of data (for understanding data so well that we can “forge”/simulate them) Testing of hypotheses based on data (the gamble) Diagnostics of problems in data (being critical) Concepts: Population vs. sample Parameters vs. statistics Probability and uncertainty Normal distribution (“bell curve”) Sample-to-sample variation of statistics!!!!!!!!!! Stay tuned… What is data? Examples: The values of a battery of standard blood tests on patients of a hospital The purchase records of customers of Whole Foods Supermarkets Demographics and survival of passengers on the Titanic* Compensation of CEOs of US companies * The responses of randomly selected people about the job performance of the US president * Gas mileage & weight of the model 2003-4 cars * Climate ratings of metropolitan areas of the US * US Stock prices at the end of the trading day (?) Stock prices of Google from IPO to end of ‘05 * Data = Recorded characteristics of a set of objects Objects = patients, customers, respondents, CEOs, car models, metro areas, US companies, dates, … Characteristics = blood values, purchases, approval opinion, compensation, mileage & weight, climate ratings, stock prices (twice), … Target format of data: table consisting of… Rows = objects, “cases”, “records” Cols = characteristics, “variables”, “attributes” ^Statistics^ ^DBs^ Classification of Variables: Qualitative: “label data” or “grouping data” o Nominal (including binary): no order red/green/blue/yellow, female/male, yes/no, … o Ordinal: labels have an order approve > don’t know > disapprove, “On a scale from 1 to 5 how do you feel about…?” Grades (A+ > A > A– > B+ >…), … Quantitative: “number data” where number means number o Discrete: usually counts # heads in 10 coin flips # dropouts from a high school # seats in a car model # trades of a stock, … o Continuous: usually measurements Interval scale: changes are expressed as differences Temperature Height of children Bank account balance, … Ratio scale: changes are expressed as ratios or percentages; the values are positive Salaries Stock price Adult weight of animal species, … JMP: Variables are marked with symbols according to type. Nominal Ordinal Quantitative Unfortunately, JMP uses the term “continuous” where we say “quantitative”. JMP would call a count variable “continuous”, which is not very sensible. Strange aspects of variable classification: The classification of a variable may depend on the purpose. For example, if a quantitative variable takes on only few different values, one might want to use these values to group the data. (Example: the number Cylinders or the number of Seats in car models.) In this case one wants to use the numbers as labels of groups, which implies that one wants to turn the variable from quantitative to ordinal. The conversion from quantitative to ordinal can be done in JMP as follows: (Right-click on the variable name) > Column Info… > Modeling Type > Ordinal > OK If a variable has values that are taken on by more than one case, the values are called ties. Ties occur naturally when the values are a small number of different counts (examples again: Cylinders, Seats in car models), or if the values are rounded, as in SAT scores which are rounded to nearest multiples of 10. Two special types of quantitative variables: Time: usually dates, daily, monthly, yearly; Time series = data with a time variable “simple” vs. “multiple” time series: o Ex. of a simple TS: daily stock prices of one company o Ex. of a multiple TS: daily stock prices of several companies Space: usually location, long. & lat. (& height), city, county, state, country Spatial data = data with location variables o Ex.: metropolitan areas Beware: Time and space are sometimes not explicit in the data. Time can be reflected in the order of the cases. Space can be reflected in names (“Philadelphia”). Use this implicit information, even if you have to find explicit dates and long./lat. elsewhere. Example: For the dataset ‘PlacesRated.JMP’, someone collected longitudes and latitudes for the metro areas and added them to the data table so we can draw maps. Data Analysis, Step 0: Sanity checks Eyeball the data table (spreadsheet) by scrolling. Check the sample size N (= # of rows, cases). Check the number of variables (= # of columns) Data Analysis, Step 1: Plotting the Data (Chap. 2) Qualitative and discrete quantitative data: o One variable: barplot (Sec. 2.2) for comparing frequencies o Two variables: mosaicplot (not in book) for comparing conditional frequencies o Pie charts (don’t use them, they are bad; P. 16) Quantitative data: o One variable: Histogram (P. 27 ff) Boxplot (not in book) o Two variables: Scatterplot (Sec. 2.5) Two variables, quantitative vs. qualitative: Comparison Boxplot (not in book) Time series: scatterplot of Y vs. time Time series plot (Sec. 2.3) Spatial data: scatterplot of long. and lat. where point markers code a variable Y with color and/or size and/or shape. Geographic map with markers (not in book) Conventions: When plotting two variables, X horizontally and Y vertically (mosaic plots, scatterplots, comparison boxplots), we say: we plot “X and Y”, or we plot “Y versus X” or “Y against X”, in this order. Also: ‘Graph’ = ‘Chart’ = ‘Plot’ Opening Datasets in JMP To open up a dataset in JMP, the dataset should preferably be in .JMP format (Excel, text and other formats are also accepted but may be trickier to read correctly). Click, for example, on ‘PlacesRated.JMP’ in webCafe’s folder ‘Datasets’. You can also click the JMP icon to start JMP and click the folder icon to open a dataset. Plotting in JMP JMP has a mind of its own. You do not tell JMP to make a bar plot or a scatterplot. You only tell it to plot one or two specific variables, and depending on their types, it will choose the plot for you, roughly following the recipes on the previous page. For plotting one variable at a time: Analyze > Distribution. Select more than one variable to get more than one plot. For plotting two variables against each other: Analyze > Fit Y by X. Selecting more than one X and/or Y variable causes all possible pairs of plots of X’s and Y’s to be made. Barplots: One qualitative variable SURVIVED CLASS crew yes 3rd 2nd no 1st Barplots allow comparisons of frequencies of labels/groups of a qualitative variable. In the examples (titanic.JMP) we see that many more passengers on the Titanic did not survive than did (left), and that 3rd class was the most populous class, apart from the crew, which does not count as a class. JMP: Analyze > Distribution > (click on qualitative variable(s)) > Y, Columns > OK Mosaic Plots: Two qualitative variables SURVIVED 1.00 yes 0.75 0.50 no 0.25 0.00 1st 2nd 3rd crew CLASS Mosaic plots show vertically proportions of the groups of the Y variable conditional on the groups of the X variable, and they also show horizontally the proportions of the groups of the X variable (in terms of the width of the bars). In the example, we can compare the survival frequencies by passenger class on the Titanic. JMP: Analyze > Fit Y by X > (click on a qualitative variable) > X, Factor (click on another qualitative variable) > Y, Response > OK Histograms and Boxplots: One quantitative variable (TotComp+opt exer) /1000 log(TotComp+optexer) 8 7 6 100000 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 Histograms show frequencies of values in equi-spaced disjoint intervals of a quantitative variable. Histograms are good for seeing the overall shape of the distribution: symmetry, skewness (one side is heavier than the other), modes (= local peaks) [see textbook] In the example (CEO_compensation_2003.jmp) we see that the distribution of CEO compensations (plus exercised options) is skewed upwards. After taking logarithms (right), the histogram looks more symmetric and bell-shaped, with only a small bin of outliers on the lower end. Boxplots show “location”, “dispersion”, and extreme observations (outliers). o The box reaches from the upper to the lower quartile (25% points from above/below), hence covers the middle half of the data. o The line in the center of the box shows the “median” (50% point) o The lines on both ends (‘whiskers’) indicate what JMP thinks is the normal range. o The points on either ends are what JMP thinks could be suspiciously extreme points (‘outliers’). In the example above, the left boxplot of CEO compensation is not very meaningful because of the extreme skewness. For the more symmetric distribution on the right, the boxplot is quite informative. JMP: Analyze > Distribution > (click on quantitative variable(s)) > Y, Columns > OK JMP produces histograms and boxplots in pairs, side by side. One can generate multiple plot pairs by selecting more than one variable at a time. Scatterplots: Two quantitative variables 70 MPG Highway 60 50 40 30 20 10 2 3 4 5 Weight (000 lbs) 6 Scatterplots show associations between two quantitative variables. They can also reveal natural groupings and extreme observations. In the example (Cars_2003-4.JMP), we see that car models with greater weight get fewer miles to the gallon. There is an extreme case in the upper left. There is some grouping visible on the right. Warning: Scatterplots do not tell you if there are so-called tied values or simply ties in a variable, that is, several cases have the same value. Ties are a problem because they result in overplotting of several cases on one point, and one cannot tell. JMP: Analyze > Fit Y by X > (click on a quantitative variable) > X, Factor (click on another quantitative variable) > Y, Response > OK Comparison Boxplots: One qualitative & one quantitative variable 70 MPG Highway 60 50 40 30 20 10 3 4 5 6 8 12 Cylinders Comparison boxplots allow us to compare the values of a quantitative variable across the groups of a qualitative variable. In the example (Cars_2003-4.JMP) we see that with an increasing number of cylinders, cars get fewer miles to the gallon. JMP: Analyze > Fit Y by X > (click on a qualitative variable) > X, Factor (click on a quantitative variable) > Y, Response > OK (click the little red triangle in the top left of the plot (!)) > Display Options > Box Plots (third down the list) Time Series Plots: Time and one quantitative variable 100 90 80 70 %Appr 60 50 40 30 20 10 11/01/2006 02/01/2006 05/01/2005 08/01/2004 11/01/2003 02/01/2003 05/01/2002 08/01/2001 11/01/2000 0 Date Times series plots are like scatterplots, except that the X axis is time and the points are usually connected. In the example (BushJobRatingsGallup.JMP) we see the President’s approval ratings according to Gallup. Note that we included the full range of percentage values from 0 to 100 on the vertical axis. This was done by rescaling the Y axis; JMP’s default is a plot that only shows the data range plus very little margin. JMP: Graph > Overlay Plot (click the time variable) > X (click a quantitative variable marked [C]) > Y > OK (click the little red triangle in the top left of the plot (!)) > Connect Thru Missing Geographic Map with Markers: Space and one other variable 50 12 Anchorage, AK Latitude 45 Clim ate-Ter rain 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 40 35 30 25 -130 -120 -110 -100 -90 Longitude -80 -70 This is a scatterplot of latitude against longitude, with the points (markers) shown in different color, shape, size. (A proper map would also show outlines of political entities and coast lines.) In the example (PlacesRated.JMP), a variable “Climate” is used for color coding. Red is the best climate, blue the worst. What do you know about the weather in Washington State, and what does the map tell you? JMP: Analyze > Fit Y by X > (click on longitude) > X, Factor (click on latitude) > Y, Response > OK > Rows (on top toolbar or on bottom left panel of JMP window) > Color or Mark by Column… > (click on a variable to be used for color coding) (check ‘Continuous Scale’ if quantitative, 4th line from below) (check ‘Make Window with Legend’, 2nd line from below) > OK [Add an example with qualitative variable for coloring.] Generalities about JMP Data Tables A JMP data table looks like a spreadsheet, but its manipulations are different from those of Excel. Every JMP table has a first column filled with case/row numbers, and a top row filled with variable names. If the data have case/row names, these need to be put in a separate column which JMP will consider as nominal. To the left of the table are three boxes: the middle box lists the variable names with type symbol, and the bottom box shows the sample size N (= number of cases/rows), as well as the number of ‘Selected’, ‘Hidden’, and ‘Excluded’ cases (see later). Most of our work will be done by using the ‘Analyze’ button in the top toolbar. We will also use the ‘Graph’ button for time series plots, and ‘Tables’ for sorting of columns. Tiny downward red arrows contain menus with actions on columns, rows, plots. Tiny blue arrows close parts of tables and plots that you may not want to see. Generalities on Manipulating Plots in JMP Plot Resizing: Place the cursor on the bottom right corner of the plotting area (not the window!). When the cursor turns into a diagonal double arrow, drag. To equalize the sizes of all plots of the same type, depress <Ctrl> while resizing. Axis Rescaling: To rescale the horizontal axis (changing the shown range), place the cursor on the extreme end of an axis in the tick/label area and drag in either direction. (It is often useful to widen the range of scatterplots a little, e.g., when the points in the plot reach too close to the margin, or when a percentage variable should show the whole range 0%-100%, or when the scale should include the zero value so as not to inflate the impression of the variation.) Axis Shifting: To shift the horizontal axis, place the cursor somewhere in the middle of the axis in the tick/label area and drag in either direction. Histogram bin widths can be changed by clicking the hand symbol (‘Grabber’) in the second toolbar from the top and dragging left-right in the plotting are of the histogram. The bin locations can be changed by dragging vertically. [After these operations, change the cursor back to the diagonal ‘Arrow’.] Selecting, Labeling, and Changing Markers Selecting: Click at a point or a bar in a plot, and the corresponding case(s) will be ‘Selected’ by JMP. The selected row(s) in the JMP table will light up, and the count of ‘Selected’ increases in the bottom left box of the spreadsheet. In plots that show points, one can form rectangles with a dragging motion, and points inside the rectangle will be selected. Accumulate selections by keeping <Shift> depressed while selecting. Deselect by clicking in white space. In a scatterplot, when the cursor hovers over a point, a row number or label will identify the case. o To choose variable values as labels, go to the center-left box in the spreadsheet, the list of variable names, then right-click on the variables of your choice and select ‘Label/Unlabel’. Operating on selections: o To make labels of cases stick, select them, then: Rows > Label/Unlabel. (See the map above.) o To change markers of cases, select them, then: Rows > Markers. o Colors of points and bars can be changed after selecting them and: Row > Colors. Linked Plots Selecting by clicking on points and bars is especially powerful when there are multiple plots of the same datasets, usually showing different variables. The selected cases will light up in all plots simultaneously (so-called ‘plot linking’). Examples: o Linked barplots show broken bars according to the selected subset. This way we see (absolute) frequencies of the selections, whereas mosaic plots would show proportions of the groups according to the vertical variable. (The vertical variable in mosaic plots corresponds to an imagined binary variable given by the selection.) SURVIVED CLASS cr ew ye s 3r d 2nd no 1s t o Linking a map to other plots allows you to see where the selected places are. 60000 50 50000 45 Latitude 40000 40 30000 35 20000 30 25 -130 10000 -120 -110 -100 -90 Longitude -80 -70 0 The Arts Importing JMP Plots and Tables into MS Word Click the fat ‘+’ symbol (‘Selection’) on the second toolbar from the top. Then click inside the area you wish to import to MS Word, but as close to the border as possible. Try a few times till the proper area lights up for selection. Then as usual: copy/paste from JMP to MS Word. To accumulate selections, hold <Shift> depressed while selecting. [Return to the usual cursor by clicking the diagonal ‘Arrow’ in the toolbar.] Multiple figures can be set side-by-side instead of on top of each other by highlighting them and doing the following in MS Word: Format>Columns…>Two or Three