outline1

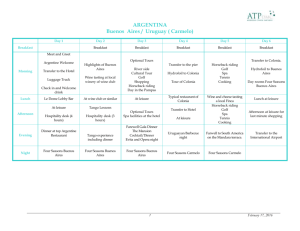

advertisement

Outline for Argentina, A City and A Nation By James R. Scobie Chapter 2- Spanish Towns Conquistadors established towns that could administer and control the Indian cultures already tied to the cultivation of the land Patagonia, the pampas, and the Chaco remained Indian territory until 19th century because they contained no settled, agrarian cultures First Spaniards came to mouth of the Rio de la Plata in Jan 1516, chief navigator Juan Diaz de Solis 1519- Magellan (Magalhaes)- claimed southern land (the pampas, etc.) for Spain 1530s- dream of silver and the threat posed by Portuguese claims to the Rio de la Plata made Spain launch a huge expedition Name Buenos Aires actually comes from Italian- Neustra Senora Santa Maria del Buen Aire Basis for colonial development became neglect of the inhospitable coast and the fall of the interior to conquistadors from Peru and Chile Small towns with vecinos (conquistadors and descendants) formed upper class- creole, ‘pure origins’, married only within their own circle, and held land and power As towns expanded, urbanized laboring class developed- outnumbered the creole class by 1600 Interior towns developed to supply the mining region of Upper Peru Urban settlement of coastal regions lagged behind the interior by a couple of decades Buenos Aires est. 1580 Conditions of life contributed to a more egalitarian type of society- absence of Indian servants Principle motive for settling coastal towns was need for commerce- provide Asuncion with an Atlantic outlet Conquistadors and creoles never became farmers- almost all the Indians- from remains of Indians a lower class was formed- Indian blood but not many indigenous cultural traits 1700s- Spaniards attracted by opportunities of commerce and demand for artisans, tradesmen, and laborers After this influx, Spaniards and creole were not necessarily upper-class- further mixed marriages and miscegenation Private ownership began to acquire importance as a means of prestige and position System of trade licenses gradually expanded to permit exchange between any port in Spain to the overseas, and then finally between the overseas ports themselves Royal measures aimed at developing production and settlement in the coastal region These policies contributed to huge rise in population along the coast- esp Buenos Aires- 12000 inhabitants in 1750 to 50000 by the end of century Much more modest development in the interior towns- began a divide between interiors’ small local industries and coast’s commercial and livestock economy Creole demand for independence begins in Buenos Aires after Viceroyalty is established there and their political roles are trivialized Countryside contained more than 3/4ths of population, but power lay in the coastal regions- interior vs the coast and creole vs non-creole became two huge points of contention through the future Chapter 3- The Rural Economy of Buenos Aires Livestock principle products and exports for pampas region from 17 th-late 19th century By 19th century, Buenos Aires monopolized all trade- everything determined by ownership in the industry Shortage of labor and remoteness from Upper Peru combined with existence of large herds to create an economy based on that Society based on leather- no attempt to export meat yet (no way invented yet) Landownership slowly replaced herd ownership as keys to power as production increased Royal sales were various- charges on large amounts of land were as exorbitant as small piecesbasically eliminated small landholders Tenure required financial resources and political influence Drifting, squatter existence for most of rural population Needed to find a way to use the carcasses of all the cows and horses- introduction of salted meatsaladero- meat salting factory- first factories in a pastoral society Didn’t show up in Buenos Aires till 1810, but the development along the Uruguayan shore intensified economic shift to the coastal regions Creole irritation with trade restrictions and ineffectiveness of Spanish rule eventually led to a struggle for independence British invasions had an immediate result- textiles and hardware came into Buenos Aires- showed the advantages of world trade 1810- dissolution of the interim government in Spain left the overseas empire without a link to the crown and gave the creoles an opportunity to break with Spanish monopoly May 25th, 1810- Creoles take over the government to rule in the name of the crown- not independence, but signified separation from the empire Opened Buenos Aires to world trade- quickly eclipsed any economic benefits of crop farming and local industries in the interior- made the split between coast and interior even bigger Juan Manuel de Rosas- signified the rise to power of the cattle interests Coast demanded free trade while the interior demanded protectionism Liberals vs Conservatives: Liberals- wanted crop farming, immigration and technology to transform and modernize the country Conservatives- wanted to continue the pastoral economy and increase profits simply by expanding the estancia and the saladero Landowning and cattle interests were combined in one really powerful group which had consolidated its wealth by means of independence and world trade- soon gained support of creole governments at Buenos Aires Fundamental conflict between grazing and crop farming economies- ultimately grazing won out Export trade and countryside both hurt by civil wars and blockades- led to financial crisis of 1838-40 and 1846-48 Fall of Rosas signified end of saladero expansion- rise of sheep raising Sheep raising stimulated immigration, rural population, expansion into the pampas, introduction of techniques in livestock care Industrial Revolution and increased carpet and weaving factories in Europe raised demand for wool Intensive use of land and rise in value pushed cattle west and south toward the frontier Immigrants were able to become independent sheep farmers within 3-4 years- laid foundations for modern Argentina’s largest fortunes This ability to move up the social scale stimulated immigration and expansion of sheep raising Significant railroad expansion in the sheep zones of Buenos Aires in the 1880s Chapter 4- From Colony to Nation Buenos Aires and other urban centers formed basis for strong national authority while the interior struggled unsuccessfully to maintain freedoms Pressure for independence concentrated in Buenos Aires- Spanish political and commercial influence seen most clearly here- tensions between creole and Spaniard, landowner and royal official Each town and rural district had its influential creole families for leadership and to work with government officials Creoles in some areas began to assume control over local municipal governments during 1810 14 autonomous provinces based on colonial municipalities Federal Pact of 1831- between Buenos Aires, Entre Rios, Santa Fe, and Corrientes- gave governor of Buenos Aires power to represent the provinces in international and financial matters Steady shift of prosperity to the coast- concentration of capital, immigrants and shipping with parallel decline of the interior Capital gradually abandoned industry and commerce for secure land holding- lower classes were constantly insecure- led to disappearance of trained, disciplined laboring class- nomads replaced artisans Absence of central authority gave all caudillos their own power- higher taxes in the interior resulted in higher costs for the consumer and lower profits for producers Demand from US and Europe for hides tallow and wool led to increase of trade from Buenos Aires All this stuff stimulated Buenos Aires and barely touched the interior Italians dominated the river trade Immigrants: a little capital sons of middle class families no intention of staying manual labor was key to success Trade benefited Buenos Aires as well as England- this tied their economy with a major financial power Class structure remained intact for a loooooong time- 19th century disorganization and economic decline finally made that change Philosophy of the Enlightenment- Rivadavian projects (continued even after the defeat of his reforms): University of Buenos Aires Public libraries Museums Efforts to separate Church and state Formation of the Generation of 1837 Rosas overthrown in 1852 1852-1880- reinforced porteno influence and power- increasingly supported the autonomy of Buenos Aires against central authority represented by presidents, ministers and congressmen from the interior provinces Political initiative shifted from strong man to intellectual Economic factors rather than government policies attracted immigrants to Argentina Total imports began to rise drastically- manufactured goods and foreign investment By 1880, Argentina relied heavily on foreign capital (mainly British)- railroads were the most important development- accentuated importance of trade centers and drained products and talents to the coast Generation of 1837 came back to Buenos Aires in 1852 and modernized through education, immigration, constitutionalism, and material progress Immigrants began to reach into all levels of society Chapter 5- An Agricultural Revolution on the Pampas Crop farming expanded because of railroad systems Active recruiting of immigrants from Switzerland and Italy Principle reason for European immigration after 1870 to Rio de la Plata was the dream of owning land Territorial expansion continued after “Conquest of the Desert” in 1879-80 and the removal of Indians Roca assumed presidency in 1880 Frozen meat shipping transformed trade in 1880s Peasant farmers from Italy formed bulk of farming class- positions of sharecroppers available Rapid economic growth resulted from the agricultural development of the Pampas- major producer of wheat as well 1900- England closes its port to live cattle from Argentina due to disease, which greatly empowered the packing plants 1900- Sheep industry took huge blows- depression of wool industry in Europe along with loss of sheep in floods caused capital to flow into meat instead Second economic boom- 1904-1912 Educational facilities declined sharply once out of the cities Isolation dominated life on the Pampas Sense of the temporary in farming- difficult for a small cultivator to secure a land title and huge demand for tenant farmers- extensive rather than intensive agriculture- fostered transiency Revolution on the pampas worked against small farms, improved roads, rural social institutions and better housing No opportunity for the rural inhabitant to advance Immigrants found most of the land already in holdings, therefore they built up in the cities Huge change in Buenos Aires- craze for modernization- agricultural revolution led to urban growth Different groups didn’t really isolate themselves in Buenos Aires, resulting in lots of mixed marriagesno real sense of national identity yet- so many different classes, so many nomadic people, and so many different cultures all mixing together, with many inhabitants planning on going home eventually Chapter 6- Two Worlds Antagonism between provincial and porteno, agricultural expansionism and home industry protectionism, immigrants vs Hispanics Search for national identity Isolation of the interior- since railroads met the needs of exporting, not many roads, busses or trucks were used at all until the 1930s Efforts to attract capital relied on guaranteed returns of investment rather than on land grants- if land grants were used, there would’ve been more development of the small farmer Tucuman and Mendoza- sugar and grape production helped them prosper even though they weren’t coastal regions- but wealth concentrated with the elite Coming of railroads increased immigrants to Mendoza and San Juan- became owners of small vineyards- technology concentrated power in major wineries, but there were enough smaller ones to produce competition Railroads insured the subservience of the interior provinces to the coastal economy Government- president had constitutional authority for intervention, power to assert national authority throughout the republic- politics centered on control of national administration A few secondary centers arose in the interior after 1900 thanks to the railroad, but nothing compared to the coast Foreigners added little to the population in the interior, therefore the culture didn’t change as it did in the coastal regions- elite was still made of descendants of conquistadors Gradual disappearance of local autonomy turned provincial governments into extensions of the national authority- limited commercial expansion Serious tension between Church and state Middle class of interior was a social rather than economic group- wholly urban class comprised mostly of foreigners- possessed no common bond and principle motivation was economic advance Urban lower class constituted 90% of urban population Indian element blended into the mestizo lower class Chapter 7- The City and the Factory Urbanization and industrialization became the fundamental factors in Argentina’s modern growth Buenos Aires- terrible hygiene and no sanitation system 1905- electricity had replaced horses Sudden development of transportation caused urban sprawl Barrio- tons of neighborhoods- each one needed its own services- made lots of jobs for immigrants (butchers, bakers, candlestick makers…) No real caste system like in the interior- social upward mobility was totally possible- elite class remained small Prior to 1880s, there were only 2 classes- socially acceptable and everyone else- after this emerged a middle class- by 1914 constituted a third of porteno population but lacked unity By 1914 the lower classes weren’t necessarily mestizo or mulatto- instead, European Economic benefits still very slow in reaching the lower classes Formation of Socialist Party in 1890s showed that the lower class had want of upward mobility too Industrial revolution followed closely on the heels of agricultural revolution- same ingredients as agriculture: Immigration Railroads Urban centers Technological and managerial skills Foreign and domestic capital Industrialization didn’t promise balanced growth, equal distribution of wealth or economic independence Industrial capital gravitated toward the processing of raw materials Economic planning was nonexistent Industry pre-WWI was weird: Large scale establishments- meat packing, tanning, flour, electricity and gas, sugar, breweries, paper, wineries, lumber, textile Bunch of small factories- shoes, bread, paints, bricks, cigarettes, glass, hardware, furniture, candies, liquor, butter, acids, suits, grain sacks- kept in marginal positions War meant that Argentine consumer could not rely on imports of consumer goods- had to rely on domestic factories 1920s- economy throve on exports of wheat, corn, beef, mutton and wool World Wars brought European immigration to an end Chapter 8- Consolidation of a Nation Establishment of Radical Party and 1890 revolution signified first real uprising against oligarchy Still struggle with national identity- foreigners never thought of themselves as Argentines First restrictive measures against foreigners were in early 1900s- threats to expel any foreigner making political unrest 1884- Anti-clerical act- removed church from teaching role in public schools- greater control over education by the government Most political unrest in 1890s came from the middle classes Economic boom gathered all elite into one national party- but self-interest led to political and economic crisis of the 1890s Union Civica- protest fighting for suffrage without corruption in the government Economic crisis of 1890- immigration ceased and emigration rose, banks closed, moratorium on businesses, etc. End signified when Roca took office in 1898 again- oligarchy kept power for another 15 yearstempered the economy Hipolito Yrigoyen- leader of Radical party Anarchism- popular with lower classes- hated and feared by elite and middle Radicals won presidency in 1916 elections- Yrigoyen became president By 1910 Buenos Aires was the cultural mecca of South America