Trench Warfare What was life like for the average soldier on the

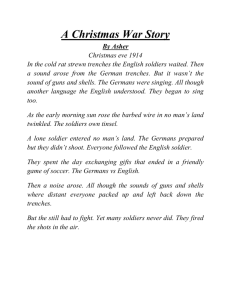

advertisement

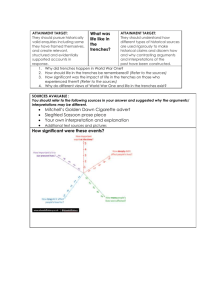

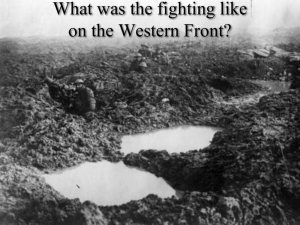

Trench Warfare What was life like for the average soldier on the Western Front? Men might have different experiences of life on the Western Front depending on their rank and role. For example, it was the job of the Officer to lead night patrols, to organize the men and to relay orders from High Command. It is said that they were treated better than ordinary soldiers as they had small 'dug-outs' in trenches where they would eat and sleep, better food and might be more readily excused from front line duty if they were wounded or ill. A typical British officer dugout, © IWM Shell-holes often doubled as trenches as the land was repeatedly bombed, © IWM In general all soldiers followed a basic routine shaped by 'stand-to' at dawn and dusk, when poor visibility made enemy attacks more likely. In the morning this lasted roughly an hour after which rifle equipment was cleaned, breakfast served and daily tasks assigned. Tasks might include repairing duckboards, draining trenches, and reinforcing trench walls damaged by rainfall. Wherever possible men tried to catch a little rest or attend to more personal matters such as writing letters home. It was at evening stand-to that work began in earnest. In this time supplies of food and ammunition were brought from the rear lines, barbed wire defences were repaired, men were rescued from no-man's land to be treated or identified, and reconnaissance work was undertaken. In theory men did a stint in the front line followed by a short spell in support, before moving to the reserve trenches. After a short rest period the pattern started again. In reality this system of rotation and leave depended on the demands of battle. Thinking Point: What do you think was the worst part of trench life? The boredom and grind of the daily routine was endured in the most appalling living conditions. For example, apart from the constant threat of enemy snipers, poison gas, shells and machinegun fire there was the difficulty of getting hot food to the front lines, so men had to rely mainly on basic food rations. These rations consisted of bully beef, tea, hard biscuits and bread, which was often stale by the time it reached them. In the winter, the ground was frozen and hard, in autumn rainfall turned the battlefields and low-lying trenches into mud baths. In some parts the water reached waist height. This could cause 'trench foot' where the feet would swell and in some cases turn gangrenous and need amputating. Mud was reported to be waisthigh at Passchendaele, © IWM Captain Ulick Burke MC, wrote: 'The conditions were terrible. You can imagine the agony of a fellow standing for twenty four hours sometimes to his waist in mud, trying with a couple of bully beef tins to get the water out of a shell hole that had been converted to a trench with a few sandbags. And he had to stay there all day and all night for about six days. That was his existence.' Corpses could not be buried quickly enough, and were often dislodged by shelling, © IWM Conditions were no better in the spring and summer months when lice, rats and flies thrived. The rats could grow to the size of cats feeding off men's rations and the plentiful supply of rotting corpses that were littered around no-man's land. Lice were not only a source of irritation and discomfort but also carried the threat of trench fever. To make matters even worse there was an ever-present stench caused by the open latrines, rotting bodies and the chloride of lime used to combat the threat of disease. What was it like to go into action on the Western Front? Unlike previous wars, fighting on the Western Front was characterized by 'trench warfare'. Each side had developed an elaborate system of reserve and support trenches with the opposing front lines separated by an area called 'no-man’s land'. From the beginning both sides hoped for a decisive battle that would end the stalemate and win the War. It was thought that the only way to achieve this was to kill enough enemy soldiers to force the other side to surrender. An offensive would start with a huge onslaught of artillery fire on the enemy line. This was designed to break down barbed wire defences, blow gaps in the opposing trenches and kill enemy soldiers. On the commanding officer's whistle soldiers in the front line climbed 'over-the-top' and with bayonets at the ready they advanced into no-man's land, facing a heavy barrage of shells and machine gun fire as they went. '...the Order comes down, 'Cigarettes Out and no noise' and then you know you have not many minutes to go before the terrible clang starts to assist you in that terrible task you have before you and behold it is hard! Every man for himself, and not one must shirk his duty, but no never a man thinks of doing such a thing as that. He knows what he has to do and leave it to him, he will do it with all his heart. And would you think for one minute that there is a smile on his face? "Yes, there is," and the words come from his mouth, "Best of luck to you old mate, let's hope you will make a good job of it."' Pte G Ward, 1916 Over the next four years hope turned to despair as offensive after offensive failed to break the stalemate and the futility of war became all too apparent. 'One sees things from a different standpoint out here, the seeming uselessness of it, day after day in the trenches with great exposure, and very little really happening. Of course occasional bombardments and it is wonderful what men can put up with.' 2nd Lieutenant John Staniforth In spite of the hardship a spirit of comradeship and high morale did exist in the trenches. As this letter from Dr. Noel Chavasse, June 6th 1915 shows: 'Last night I had a bad but necessary job. I had to crawl out behind part of the trench and bury three poor Englishmen. … This is the seamy side of war, but all is repaired in the feeling of comradeship and friendship made out here. It is a fine life and a man’s job.' When fear and trauma got the better of some men their behaviour was seen as cowardice or weakness. Men were court-martialled and, in some cases, shot. This harsh attitude and military discipline no doubt had an effect on why men continued to fight – they had no other choice. As this extract from Captain T.H. Westmacott 14th April 1916 shows: 'The man had deserted when his battalion was in the trenches and had been caught in Paris... The condemned man spent the night in a house about half a mile away. He walked from there blindfolded with the doctor, the parson and the escort. He walked quite steadily on to parade, sat down in the chair, and told them not to tie him too tight... On the word "Fire!" the man’s head fell back, and the firing party about turned at once.' It was not until later that this 'cowardice' or 'desertion' came to be recognised as a medical condition called shell-shock. 'One look-out fellow suddenly went chumpy and dashed away. I chased after him into a dugout where I found him trembling from head to foot. All he could say was "I can’t stand it." Poor devil. He had shell-shock some time ago.' Major Schweder, April 1916