The CCCMS61 has is one of the most famous

advertisement

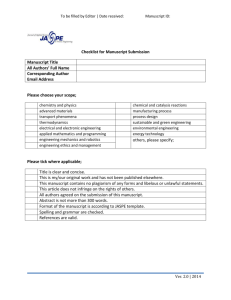

Michelle Doherty LIB 490 Matthew Goldie December 16, 2001 Illuminating the Troilus Frontispiece and the Scrope Family Connection The Corpus Christi College, Cambridge MS 61 frontispiece to Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde is one of the most beautiful and lavishly decorated prefatory miniatures of the early fifteenth century. The elaborate design of the Troilus frontispiece was the first English work of its kind. Even the manuscript of Troilus and Criseyde that was commissioned for Henry V while he was still Prince of Wales does not approach the design for illumination intended for the Corpus Christi manuscript. However, the manuscript’s enigmatic qualities have left scholars with many questions. Is this a recreation of an actual historic event? Can the elegantly dressed group of nobles situated in this idyllic garden scene be accurately identified? While “many hours of pleasant speculation” can be spent answering these questions “no art-historian would countenance for a moment the identification of all the minor personnel of a picture when there are no specific identifying features such as coats of arms, insignia or characteristic costume” (Salter 108). In spite of the lack of heraldic evidence, it is possible to identify the main figures in the frontispiece by using the style and artistic content of the miniature to compare the manuscript with other manuscripts of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. This also makes it possible to connect the Troilus frontispiece to other manuscripts produced by the same limner or artist. Identifying the artist provides the link needed to Doherty 2 identify the most likely patron of the manuscript as Stephen Scrope, Archdeacon of Richmond. Once the patron is identified it gives a better understanding of the limner’s portrayals of the scenes in both the foreground and the background, which in this case function in a sense as “companion pieces” (Salter 17). Although it may be possible, and reasonable, in an artistic context, to identify the three main figures in the foreground, this is by no means an historical representation of a reading, or more accurately, since no book is present, of a recitation. Stephen Scrope’s devotion to his Uncle, the Archbishop Richard Scrope, is well documented in service, by his request in his will to be buried alongside his uncle and in his earlier commissioned manuscript depicting Richard with Stephen’s namesake saint, St. Stephen. The foreground scene in the Corpus Christi manuscript is representative of a time in the Scrope family history when they were in the court’s favor - before Fortune’s wheel turned again. The background scene is a reminder of the “double sorwe” of Troilus who went from “wo to wele, and after out of joie” and perhaps reflects the fall of the Scropes as well. If this miniature was designed by the limner for Stephen Scrope in memory of, or as a reflection of his devotion to his uncle the Archbishop, then a reminder of the changing rise and fall of Fortune’s wheel would have been appropriate in keeping with both the turbulent history of the Scropes and the themes of Troilus and Criseyde. Identifying the central figures in this portrait allows the reader to place more emphasis on the theme of the “double sorwe” of Troilus and of Fortune and her wheel. After presenting a general description of the frontispiece, I will concentrate primarily on the foreground and the possible identification of the three main figures there based on evidence found mainly through art history and comparison with other Doherty 3 manuscripts. Those identifications will place more importance on the connection between the two scenes depicted in the frontispiece as will be shown in the discussion of the background scene. The most important clues to discovering the history and provenance of the manuscript come from the style and form of the painting. Although the frontispiece in the Corpus Christi manuscript (fig. 1) is the only miniature or illuminated page in the manuscript, ample space was left for approximately ninety further miniatures and illuminated capitals. This, combined with the scribe’s use of the display script literra quadrata, which was more commonly used for liturgical or deluxe manuscripts, is indicative of the high cost of the production of the Corpus Christi manuscript. The style of the miniature is generally referred to as International Gothic. Since the Corpus Master was most likely an English artist, it is probable that he was trained “either on the Continent or by a French artist in England, who had absorbed some aspects of English book illumination, notably border design” (Scott 56). Other influences on the Corpus Master may have come from the Limbourg brothers who illuminated the Tres Riches Heures and the Belles Heures of Jean, Duc de Berry c.1409. There is a notable similarity in the richness and intensity of colors in the landscapes as well as numerous examples of divided miniatures. (fig. 2) Another possible influence on the style of the miniature, as discussed by Salter, may have come from the prefatory illuminations of Guillame de Deguileville’s Pelerinage de Vie Humaine that were “widely disseminated in France and in England” (19). (fig. 3) In illuminations of the Deguileville Pelerinage de Vie Humaine, there are many examples of recitations with monks or poets at draped podiums addressing an Doherty 4 appropriately mixed audience. The most compelling example comes from an early fifteenth century depiction of this scene as “a courtly outdoor idyll, complete with landscape detail of a stylised type, and intricate castle architecture” (Salter 19). This scene is illuminated in direct response to the opening lines of the Deguileville poem. (fig. 4) The Corpus Christi frontispiece consists of a lavishly, illuminated miniature divided into two scenes which are completely enclosed by two distinct and separate borders. The foreground of the picture, which has been commonly referred to as “Chaucer reading to the Court of Richard II,” depicts a poet or monk, standing at a draped podium, reciting to a courtly audience in an outdoor, garden setting. There are two other prominent male figures in the foreground, standing in front of the reciter that demand the viewer’s attention. These two figures are among the three that will be identified in this paper. The background, which is divided from the foreground by a rocky ledge running diagonally across the miniature, contains two castles situated high in the scene. One castle is set in the distance with a path leading downwards and one, more elaborate and with more architectural detail, sits nearer. A noble couple and their entourage stand before the nearer, more prominent castle greeting a second group of nobles whom have made their way down from the second castle higher in the background. The diagonal split in the miniature is meant to separate the foreground from the background scenes not only physically, but also with relation to time. “This design adapts a medieval pictorial convention in which an author is shown composing, accompanied by the events and personages within his work” (Windeatt 16). Doherty 5 It is important to note details in the style of the painting so that we can connect this work with previous work done by the same limner and allow us a more accurate interpretation of the prefatory miniature. When citing characteristics of this limner’s style as represented in the Corpus Christi manuscript, Kathleen Scott describes the two levels of border around the miniature – an outer border of sprays and an inner frame as: a continuous band of circular vines in various forms, all rendered in intense tones of blue, pink and orange…The spraywork outside the band frame contains pen vines with tiny green lobes (feathering), large gold balls and unusual, rather flamboyant motifs of tightly curled leaves, some with twisted lobes and smaller gold balls. An important motif found in related manuscripts is a pear shape drawn in pen and ink that encloses a minute circle and has on the outside three small green lobes and an elongated pen-squiggle. (57) Scott goes on to point out the details of the clothing in the picture. She defines the colors used for depicting costume as “intense pink and blue, a darker blue and an orange-red, all of which are modulated by deeper tones of self-colour,” and noting that only two of the figures do not follow the pattern of color described above. The poet or monk, usually accepted as Chaucer, who is “dressed in a self-effacing pinkish tan” and the figure who is the most prominent in the scene dressed “in a costume entirely of gold brocade studded with blue jewels” (56). These details are important in the dating of the manuscript. Elizabeth Salter refers to the clothing in the picture to date the manuscript to no later than 1420 (15). Scott goes further in narrowing the date to a period between c.1415-1420 by comparing the manuscripts to other datable manuscripts and associating the Corpus Christi frontispiece Doherty 6 with other works by the same limner, most notably, for this paper, the Longleat House MS 24. (fig. 5) Pearsall and Salter remind us repeatedly that any attempts to identify “recognisable ‘portraits of fourteenth century celebrities’” would be impossible and inappropriate because of lack of “art-historical and paleographical evidence” (Salter 22). However, the artistic style of the scene itself allows us to identify the main figures as characters in a scene that represents not an historical event but the image of the past as the patron or limner chose for it to be represented years afterwards. There is little argument that the figure standing at the draped podium (fig. 6) represents Chaucer himself. We are tempted to try and identify the portrait as if it were a modern portrait or a photograph. James McGregor, in his article “The Iconography of Chaucer in Hoccleve’s De Regimine Principum and in the Troilus Frontispiece,” poses an interesting question: “What do the [the portraits] tell, not about how Chaucer looked, but about how he, the first great poet in English, was looked at?” This question is particularly relevant considering that no evidence exists that Chaucer ever gave command performances for the court of Richard II. But when the miniature viewed as an artistic representation of poet and audience instead of a literal one, one can readily place Chaucer in this scene. Aage Brusendorff compares this portrait to other portraits of Chaucer, notably the Hoccleve portrait and finds it to be a similar but more youthful representation of a man of about forty years of age (Brusendorff 20). The portrait in the Troilus frontispiece was painted after Chaucer’s death in 1400. The scene may even be funerary in the sense that “the nobility [pictured] exist to compliment Chaucer, not to be celebrated in themselves – they appear only as “typical” kings and princes; they are Doherty 7 logically identifiable, therefore, but not physiologically identifiable with Richard and his court” (McGregor 347). While I agree with McGregor that most of the audience are meant to represent a “typical” court, I believe that when examined bearing in mind the artistic traditions and styles of miniatures in the fifteenth century, it is reasonable to speculate on the identification of the three main figures. There is general acceptance, among those willing to attempt identification of some of the figures, that the central figure attired in gold brocade is Richard II. (fig. 7) Scott sees this figure as the patron of the painting; however, I see no reason to dismiss previous scholar’s identifications of this figure Richard II. The patron, as will be discussed later, would definitely have been prominently represented, but based on other manuscripts, on costume and on position in the scene, this figure dressed in gold is most likely representing Richard II. Some scholars have pointed to this second figure and the reciter as a variation on a book dedication portrait. Miniatures portraying book dedications were very common in medieval manuscripts and usually portrayed the author on bended knee presenting the manuscript to either the patron or to royalty. McGregor acknowledges that although variations on the book presentation theme were widespread, none included such a strong reversal of prince and poet (346). This leads to the conclusion that this is not a book presentation but instead a reflection or comment on the patron’s relation to the court, the poet, the time period or to Richard II. Identifying the patron as Stephen Scrope would allow us to look further into those relationships. Although there can be found, for the most part, agreement on the identification of the first two prominent figures in the foreground of the Troilus frontispiece, the third figure can only be identified when we attempt to identify the patron Doherty 8 of the manuscript. The third figure central to the miniature, and the most important in determining what is being portrayed in the foreground, is the figure dressed in light blue with a medallioned collar and belt to match, standing just to the right of the poet/preacher figure at the podium. (fig. 8) This figure is set apart from the general audience both by dress and position to identify him as a person of power and importance. The patron of this manuscript would have had to come from a family of some wealth and status. The costs of this manuscript, due to the “script …were almost twice as expensive as books copied in other scripts, and the programme of illustrations on the scale suggested by the gaps and in the manner of the frontispiece would have required considerable outlay” (Harris 51). George Williams makes an argument that this third figure could possibly represent John of Gaunt. He points to the women in the foremost left hand side of the portrait, dressed in blue, to help support this claim. The woman second from the left is wearing a diadem and according to sumptuary law during the 1380’s and 1390’s “ only one other woman in England besides Queen Anne, was entitled to wear a queenly crown. This was Constance, Queen of Castile and wife of John of Gaunt.” Williams agrees that the main figure dressed in gold brocade represents Richard and therefore the woman standing to the side of him, wearing a diadem would represent Queen Anne. He also alludes to the fact that the members of what he sees as Gaunt’s household are all dressed in blue and white – the colors of Gaunt (Williams 175). These arguments do not hold up when we examine, as we have earlier, the style, colors and characteristics that the Corpus Master was known to employ. He used those particular colors of blue repeatedly in many of his illuminations, as did most limners of the period. Also, when we think of the Doherty 9 audience as an artistic representation of a courtly audience or as “’typical’ kings and princes” as in McGregor’s description, sumptuary laws are not as relevant to interpreting the image. Identifying Stephen Scrope as the person who most likely commissioned the Corpus Christi manuscript still leaves questions about the provenance of the manuscript. Scholars have looked beyond the frontispiece image to markings in the manuscript in an effort to determine the provenance. The widely accepted theory regarding the provenance of the Corpus Christi manuscript is that it was at one time in the possession of Anne Neville, duchess of Buckingham, granddaughter of John of Gaunt and distant relative of Chaucer’s wife, Phillipa de Roet. This is based on the marking “Knyvett” found on folio 108r. Sir William Knyvett was Anne Neville’s second husband. Her name also “appears in a note added to Troilus and Criseyde, IV.581 (‘neuer foryeteth: Anne neuyll’)” (Pearsall 68-9). While the manuscript may have come to be in the possession of the Neville’s they were most likely not the original patrons of the work. As stated above, the most important evidence that exists in linking this manuscript to the patron comes from the artistic style of the manuscript itself and the ability to connect this piece with other manuscripts produced by the same limner. That connection can be made between the Corpus Christi manuscript and the Longleat House MS 24. Kate Harris, identifies one of the patrons of the Longleat House MS 24, a ornately illuminated copy of John de Burgh’s Pupilla oculi (fig. 5), as Henry, third baron Scrope of Masham. There are three coats of arms present on the Longleat manuscript. The first two belong to Robert Fitzhugh, bishop of London from 1431-1436 and to Richard Holme, canon of York from 1393-1424. Holme was a King’s clerk under Richard II. Doherty 10 The third coat of arms, which is situated between the other two, has been erased. (fig. 9) Harris maintains, however, that it can still be seen faintly and that it remains possible to determine the original heraldry as it had appeared. The emblazon, azur a bend or, matches the arms of the Scrope family, and, Harris believes, Henry, third baron Scrope of Masham, who was executed as a traitor in 1415 for his involvement in the Southampton plot to depose of Henry V with the “ineffectual earl of March” (Harris 42). Although Harris identifies the correct family as the patron of the manuscript, I agree with Kathleen Scott that she may be incorrect in her identification of which member of the Scrope family commissioned the manuscript. Stephen Scrope, archdeacon of Richmond, second baron Scrope of Masham, brother of Henry, third baron Scrope, and nephew of Richard Scrope, archbishop of York, had connections to Cambridge and was Chancellor in 1414. His death in 1418 would have been a better fit with the time period indicated by the style of illumination in the Corpus Christi manuscript (Scott 61). Stephen Scrope is thought by Scott to have commissioned the Longleat MS 24 and in it are representations of what she believes to be his father and his own namesake Saint. I believe that given his devotion to his uncle it is also possible that the figure in the picture represents not his father, but his uncle, the Archbishop Richard Scrope. The Corpus Master is one of the only known limners to work repeatedly for one patron. Scott identifies the Corpus Master as having worked on numerous occasions for John Whetehamstede, Abbott of St. Albans from 1420-40 and 1451-1465 (Scott 67). Therefore, if Stephen Scrope commissioned the Longleat MS 24, it is a strong possibility that he could have commissioned a second manuscript from the same limner. Doherty 11 Stephen Scrope, brother of Henry, served as secretary to his uncle Richard, the archbishop, and was archdeacon of Richmond from 1400-1418. He was chancellor of Cambridge in 1414 and in his will had asked to be buried “beside my lord the archbishop of York, who when he was alive reached out his helping hands to me, and now he is in heaven I beg that he may pour out prayers on my behalf” (Harris 48). Stephen Scrope would have been the more likely patron of the Longleat House MS 24 Pupilla oculi considering his education and relation to the church. His uncle, the Archbishop Richard Scrope, was executed in 1405 as a traitor. He was a “leader, though not the instigator” of an uprising against Henry IV (Bolton Castle 1-2). In 1385, Richard, first Baron Scrope of Bolton (c. 1307 –1403), Archbishop Richard Scrope’s godfather, was involved in a prolonged case before the courts against Robert Grovesnor. Both Scrope and Grovesnor claimed the rights to the arms azur a bend or. The case continued for over five years. This case is particularly interesting because “Chaucer himself was called as a witness for the Scropes and gave substantial testimony” (Keen 50). This establishes a connection between the Scrope family and Chaucer. The wills of both Henry, third Baron Scrope of Masham and Stephen, Archdeacon of Richmond contained mentions and bequests of many beautifully illuminated manuscripts. There is no specific reference to the Corpus Christi manuscript, however there are a number of connections between the Scrope and Neville families. After Richard, First Baron Scrope of Bolton’s execution, his son, Richard became a ward of Ralph Neville. He fought in Agincourt in 1415 and married Margaret Neville in 1418 (Bolton Castle 3). It would be pure speculation to try and define provenance of the Doherty 12 Corpus Christi manuscript on these connections, however, no conflict exists in the dates that would prove it impossible for Stephen Scrope to have been the original patron and for the manuscript to have been in the possession of Anne Neville. There was much political tension between the Scrope family and Henry IV as well as Henry V, however the relationship with Richard II seems to have been much more favorable. Richard, first Baron Scrope of Bolton, became steward of the household on Richard II’s accession and was prominent in the first two parliaments of the reign, the second of which saw the great seal transferred to him on 29 Oct 1378. Henry, first Baron Scrope of Masham, was on the “committee of the upper house appointed to confer with the commons in the Good Parliament” and was appointed to the first council of Richard II’s minority. He attended parliament until 1381 (Scrope 138-42). There are many characteristics of the illumination (as pointed out by Scott) that connect the Corpus Christi manuscript to the Longleat MS 24 and therefore to the Scropes. It is unusual, however, for no identifying marks of the patron to be visible in a manuscript as elaborate as the Corpus Christi manuscript. In most deluxe, illuminated manuscripts the patron's emblazon, badge, colors, or portrait would have been worked into either the miniature itself or into the design of the border. The Visconti Hours, for example, an ornately illuminated book of hours produced for the Visconti family between 1402-1412, contains over one hundred illuminated plates. Almost every one includes one of the Visconti devices (a white dove, a blue viper swallowing a red man or the Visconti sun) in the border, an illuminated capital, or in the miniature itself (Meiss 32). Harris, notes that “it may be that the characteristics of a traitor’s books would include the eradication of marks of ownership and that this itself is responsible for the impenetrable Doherty 13 obscurity surrounding the origins of the Corpus MS 61” (51). With the lack of heraldic evidence, the connection based on the limner of Longleat House MS 24 and the Corpus Christi manuscript becomes key in identifying the patron as Stephen Scrope, Archdeacon of Richmond. This artistic evidence allows us to identify the third figure in the foreground of the Troilus frontispiece, positioned just to the right of the reciter, as the figure representing the patron, Stephen Scrope, and portraying either his father or more likely his uncle, the Archbishop Richard Scrope. The remaining figures in the foreground are meant to represent general characterizations Chaucer’s audience and not specific historical people. They are an artistic representation of the extended court of the time and cannot reasonably be identified. At the front, in the bottom right, can be found a pair of lovers seated staring into each other’s eyes. Chaucer’s narrator addresses lovers directly in the opening stanzas of the poem, “But ye loveres, that bathen in gladnesse” (i. 22). There are other pairs of lovers evident in the foreground as well as people in various states of attending the speaker. The scene may have been painted as an outdoor scene in the style of the landscape paintings of the Limbourgh brothers or other French and Italian artists of the time. People facing forward and not attending may have been portrayed in this manner for artistic design and only so that it would allow the viewer to see both the figures and the costuming from a more appealing angle. It is also unlikely that Chaucer’s courtly audience would have been made up of a “significant number of women, despite the poems address ‘Bysechyng every lady bright of hewe, / And every gentil womman, what might she be’ (v.1772-3), and despite the presence of women in the Corpus picture” Doherty 14 (Windeatt 16). The mixed audience is an artistic device used by the limner possibly reflecting the themes of the poem in an effort to connect the foreground and its “loveres” with the poem as well as with the Scrope family and the court of Richard II. Before making a connection between the background and the foreground, the scene being illustrated in the background needs to be explored and identified. The background of the picture is separated from the foreground by line of soft-modelled rock that runs on a diagonal across the miniature. The manuscripts of the Limbourgh Brothers were most likely a strong influence on the divided landscape of this portrait. There are some arguments that this is a royal processional in the tradition of safe passage illuminations or Itinerary scenes as in the manuscripts of the Limbourghs. (fig. 10) A processional of this type would indicate that the figures represented below were being represented again above although at a different time. However, any attempt to identify the figures in the background in a historical sense, as in the case of Margaret Galway, has been largely dismissed. More recent scholars have accepted the theory that the background is representative of a scene from the poem and more specifically that it is the scene in which Criseyde is being escorted from the city of Troy. Phillipa Hardman argues that the scene could be representing the front of the temple of Pallas as the nobility approach dressed in their best finery for the feast of the Palladium. She points to the passage in Troilus where Chaucer describes them “in al hir best wise/…so many a lusty knyght,/ So many a lady fressh and mayden bright, / Ful wel arayed” (i.162-68). Her argument falls short in its reliance on the representation of the castles instead of tents. She argues that in the traditional representation of the Troy story, Doherty 15 the types of dwellings that are used to illustrate them differentiate the Greeks and Trojans. The Greeks are “always in tents and the Trojans in the architectural surrounds of their city” (Hardman 59). The gothic illumination of this miniature is very ornate in style and would not have been limited to a literal representation of the tradition or text. It cannot, however, be ignored that the frontispiece was commissioned specifically for this work and that, like most prefatory miniatures of the time, would have represented a scene from Troilus or at least a theme presented in the poem. The scene represented here is most likely Criseyde being led from the city. By guiding us into the poem and showing us a “sad premonition” of what’s to come, it “reinforces, amongst the images of richness and beauty” (Salter 123) the narrator’s promise: The double sorwe of Troilus to tellen, That was the kyng Priamus sone of Troye In lovynge, how his aventures fellen Fro wo to wele, and after out of joie (i. 1-4) We cannot attempt to try and identify each figure in the scene, but it is possible to see the figures as representing Criseyde being led from the city towards her father who is waiting to greet her. The figure in blue turning away from her may represent Troilus. After a brief period of “joie” spent with Criseyde, fortune’s wheel turns leaving Troilus once again in sorrow. The background and foreground work together as “companion pieces” showing both the joy and sorrow of fortune. What is interesting about the background and the limner’s choice of themes is how it relates to the patron, Stephen Scrope, and his family. In addition to representing the sorrow of Criseyde being led from the city, it reminds the audience of the theme of Doherty 16 fortune’s wheel, of fate vs. man’s free will and of how Troilus went from “wo to wele, and after out of joie.” While the audience in the foreground is seated in an idyllic setting, the background is a reminder of that “double sorwe.” The Scrope family had been, during the time of Richard II, in good favor with the court; however, by the time the Corpus manuscript was created several members of the Scrope family had been executed as traitors. It is possible to see fortune’s wheel in evidence in the history of the Scrope family. Whether identifying the patron as Stephen Scrope, Archdeacon of Richmond, allows contemporary readers to interpret the poem differently ultimately remains up to the readers. The parallels between the fall of Troy, of Troilus and of the Scropes add another dimension to the themes already evident in the poem. The identification of Stephen Scrope does allow us to view the frontispiece from another perspective. In a discussion on Chaucer’s audience, Paul Strohm stated that “one definition of a classic is that it has more than one voice: that its richness permits it to speak in different ways to different people” (Chaucer’s Audience 181). The intriguing design of the Corpus Christi Troilus frontispiece continues to speak to modern viewers with its richness and beauty in many ways. Doherty 17 Works Cited Bolton Castle. 7 Dec. 2001 <http://www.boltoncastle.co.uk/history.htm> Brusendorff, Aage. The Chaucer Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1925. “Chaucer’s Audiences:Discussion.” The Chaucer Review 18.2 (1983): 175-181. Chaucer, Geoffrey. “Troilus and Criseyde.” The Riverside Chaucer. Ed. Larry D. Benson. 3rd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987. 471-585. Galway, Margaret. “The Troilus Frontispiece.” Modern Language Review 44.2 (1949): 160-177. Hardman, Phillipa. “Interpreting the Incomplete Scheme of Illustration in Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 61.” English Manuscript Studies, 1100-1700 6 (1996): 52-69. Harris, Kate. “The Patronage and Dating of Longleat House MS 24, a Prestige Copy of the Pupilla Oculi Illuminated by the Master of the Troilus Frontispiece.” Prestige, Authority and Power in Late Medieval Manuscripts and Texts. Ed. Felicity Riddy. Rochester: York Medieval Press, 2000. 35-55. Keen, Maurice. “Chaucer’s Knight, the English Aristocracy and the Crusade.” English Court Culture in the Later Middle Ages. Eds. V.J. Scattergood and J.W. Sherbourne. New York: St. Martin’s, 1983. 45-61. McGregor, James H. “The Iconography of Chaucer in Hoccleve’s De Regimine Principum and in the Troilus Frontispiece.” The Chaucer Review 11.4 (1977): 338-50. Meiss, Millard and Edith W. Kirsch, eds. The Visconti Hours. New York: Braziller, Doherty 18 1972. Pearsall, Derek. “The Troilus Frontispiece and Chaucer’s Audience.” Yearbook of English Studies 7 (1977): 68-74. Salter, Elizabeth. Introduction. Troilus and Criseyde: A Facsimile of Corpus Christi Cambridge MS 61 with Introductions by M.B. Parkes and Elizabeth Salter. By Geoffrey Chaucer. Cambridge [Eng.]: D.S. Brewer, 1978. 15-23. Salter, Elizabeth and Derek Pearsall. “Pictorial Illustration of Late Medieval Poetic Texts: The Role of the Frontispiece or Prefatory Picture.” Medieval Iconography and Narrative. Ed. Anderson, Flemming, Esther Nyholm, Marianne Powell, and Flemming TalboStubkjaer. Odense: Odense UP, 1980. 100-23. Scott, Kathleen. “Limner-Power: A Book Artist in England c. 1420.” Prestige, Authority and Power in Late Medieval Manuscripts and Texts. Ed. Felicity Riddy. Rochester: York Medieval Press, 2000. 53-75. “Scrope.” Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1987. 134150. Williams, George. “The Troilus Frontispiece Again.” Modern Language Review 57 (1962): 173-8. Windeatt, Barry. Oxford Guides to Chaucer: Troilus and Criseyde. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992. Doherty 19