The Humanics Philosophy of Springfield College

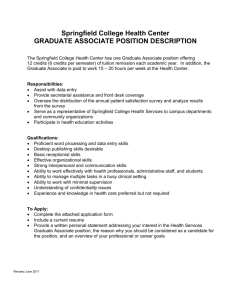

advertisement