RHIT 590R Research Methods

advertisement

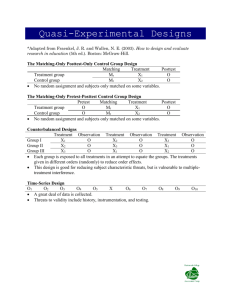

RESTAURANT, HOTEL, INSTITUTION, AND TOURISM MANAGEMENT 590R Research Methodology Class Lecture Notes - Week 9, Session 19-21. Threats to Internal and External Validity Campbell and Stanley (1963) differentiated possible confounding variables according to whether they posed threats to internal or external validity. Internal validity concerns the internal fitness or rigor of the research design. A research study increases in internal validity as the researcher controls for the possible effect of confounding variables. As the researcher controls confounding variables and thus minimizes the operation of error, he/she can conclude that any observable change in the study is due to the independent variable-not to any extraneous variables that threaten the internal validity. Threats to external validity concern the degree to which the researcher can generalize the findings to a larger population. In other words, with what degree of reliability can we transfer the results from the sample to the entire population? A) Threats to Internal Validity Campbell and Stanley (1963) delineated eight classes of extraneous or confounding variables that can threaten the internal validity of a research design: history statistical regression maturation differential selection testing attrition instrumentation selection-maturation interaction 1) History - Since most research studies continue over a period of time, other events may occur in addition to the independent variable or treatment which account for a change in the dependent measure. Example: A group of people are in a research study to determine the effect of three levels of group counseling and the effect the counseling has on the anxiety level of each individual. Each is given a pretest and posttest in order to measure the effects of the treatment. There are several confounding variables that may be 45 the reason for the change in the subjects other than the group counseling. These may include: some starting individual therapy, some going through a divorce, loss of job, death in the family, etc.. Any of these confounding variables could have influenced the posttest scores. 2) Maturation - During the course of a research study, biological or psychological processes may operate to produce a change in the individual. Physical, social-emotional, or cognitive changes may occur. Subjects may become more mature, less egocentric, or more intellectually developed than previously. Subjects may also become more or less motivated, fatigued, or discouraged than when they started. 3) Testing - In many research studies a pretest is administered, the treatment or independent variable operates, and then a posttest is given to measure the effect of the treatment. If the pretest and posttest are identical or similar, subjects may improve scores on the posttest just because of having taken the pretest. Thus subjects may become test-wise and perform better not because of the treatment but because of their experience with the pretest. As the time increases between testing, the importance of this confounding variable usually decreases. 4) Instrumentation - If the researcher tries to minimize threats caused by testing, he/she should be careful not to increase error brought on by instrumentation. If he/she changes the assessing instrument from pretest to posttest, there may be gains due to the use of a different instrument. Example: Using an easier pretest or posttest, changing the item format from multiple choice to essay, or switching the procedure from mailed questionnaire to phone interview may all cause observed changes in the group. Such changes cannot be attributed solely to the treatment or independent variable. In assessment situations where greater subjectivity may operate, the researcher must take care to minimize it. Standardization or uniformity of procedure for scoring should be established to minimize this threat. 4) Statistical Regression - Statistical regression is the tendency of extremes in a distribution of scores to move closer together, or regress, to the mean upon retesting. This phenomenon is due to the error of measurement contained in extreme scores. The more extreme a score, the larger the error it may contain. Thus, upon retesting, high scores on the average tend to decline and low scores tend to improve. 46 B) 5) Differential selection - If there is a systematic recruitment of subjects into groups, differential selection may operate. Thus, different scores on subsequent testing may be due to selection rather than the effects of the independent variable. Example - Comparing the performance of a group of volunteers with that of non-volunteers illustrates differential selection. Differences between the groups may be attributable to confounding variables that are associated with volunteers. Choosing the first 25 people to come through your door for your experimental group and the next 25 as the control group is also an example of differential selection. The most effective way to control the effects of differential selection is to randomly assign the subjects to treatments. In this way, the researcher can assume that possible systematic differences are randomly distributed between groups. 6) Attrition or experimental mortality - If there is a systematic withdrawal in the type of subjects who leave a group, the threat due to attrition may operate. Example - The lower performing subjects may drop out first; the more disturbed, the less motivated, the more creative, and so forth may systematically leave a particular treatment group. Differences ion the dependent measure could then be due not just to the independent variable, but also to attrition. If attrition does occur in a study, the researcher should attempt to measure and explain its possible effects on the results. 7) Selection-maturation interaction - Selection-maturation interaction is similar to differential selection except that maturation is the specific confounding variable. That is, a differential assignment of subjects to groups occurs in such a way that affects the maturation variable. Example - Children may be assigned to an experimental or control group in such a way that differences in maturation measures such as physical motor development or cognitive developmental level. Thus results from the variable may be du to maturation differences rather than the treatment or independent variable. Threats to External Validity: Population Bracht and Glass (1968) delineated twelve types of confounding situations that threaten the external validity of research results. These fall into two broad categories; population validity, and ecological validity. a) Population validity - deals with generalizations to populations of people; that is, what other population of subjects can be expected to respond in the same way as the sample subjects? 47 Two types of threats fall under population validity: i) Comparison of accessible population and target population - This threat concerns the extent to which the experimenter can generalize from the available population of subjects (the accessible population) to the total population (the target population). Results of the dependent measure may apply only to the experimentally accessible population from which the subjects were selected and not to the larger target population. In some cases, it may not even be possible to generalize results to the accessible population. This may operate when no inferential statistics are used to analyze the results or when there is no random selection of the accessible population. ii) Comparison of personological variables and treatment effects. Another threat to the ability to generalize results of a dependent measure is the extent to which personological characteristics of subjects interact with the treatment or levels of the independent variable. A possible confounding variable may operate so as to influence the effects of treatment and thus give results incorrectly generalized to the broader population. The best way to minimize the probability of personological variables interacting with the effects of treatment is to build these possible influencing variables into the research design and measure their relative effects. C) Threats to External Validity: Ecology Ecological validity deals with generalization about the environmental setting of the study. That is, under what variations in environmental conditions, such as changes in physical setting, length of treatment, time of day, experimenter, dependent measures, and so forth - can similar results be predicted? Bracht and Glass (1968) delineated ten types of threats: a) explicit description of the independent variable b) multiple-treatment interference c) Hawthorne effect d) novelty and disruption effects e) experimenter effect f) pretest sensitization g) posttest sensitization h) interaction of history and treatment effects i) measurement of the dependent variable j) interaction of time of measurement and treatment effects 48 A) Explicit description of the independent variable - The independent variably must be specifically delineated in the research study to ensure replication and generalization of the results. Detailed descriptions of the physical setting, of experimenter training, of the independent measures as well as explicit directions should be provided in the procedure subsection of the research article. Difficulties arise when the researcher presents concept levels of the independent variables but fail to operationalize them to allow replication. Example: Traditional and non-traditional; team and traditional teaching. If the independent variable is not operationally defined as either a measurement type or an experimental type, replication by others is possible only to the degree to which they can suppose the original meaning. B) Multiple-treatment Interference - If a researcher administers two or more treatments consecutively to the same subject, multipletreatment interference may occur. Generalizing the results of multiple treatments to settings in which only one treatment occurred threatens the validity of the results. A strategy that minimizes this threat is to randomly assign only one treatment to each subject. Multiple-treatment interference may also occur when the same subjects participate in more than one study. Each study would be considered an additional treatment. C) Hawthorne effect - Knowing that you are a participant in a study may alter your usual responses. These atypical responses are due to the Hawthorne effect. Because of it, the results cannot be explained based on the manipulation of the independent variable. Instead the effect of the situation on your responses-such as more anxious or more relaxed, more cooperative or more distracted-will artificially affect the scores of the dependent measure. Concepts related tot he Hawthorne effect are the John Henry effect and he placebo effect. The John henry effect relates to situations in behavioral research in which groups not receiving the treatment (control groups) function higher than they normally do. Traditionally the Hawthorne effect refers to any positive gains in the experimental group, and the John Henry effect to any positive gains by the control group, Historically, the placebo effect has mainly been of concern to medical and drug research. It is the extent to which the act of taking or participating in a treatment, rather than the treatment itself, influences the results. In other types of behavioral research, the placebo effect may operate in control groups that do not receive attention comparable to that given the experimental group. The ability to generalize research results should be questioned, and perhaps modified, when comparison groups are constructed in a way which does not consider the placebo effect. 49 D) Novelty and disruption effects - A new or unusual treatment may exhibit greater gains in the dependent measure when compared to the traditional treatment primarily because it is novel. As the novelty diminished with time, the greater gains of the treatment may also diminish or disappear. The counterpart of the novelty effect is the disruption effect that may operate when a new treatment is sufficiently unfamiliar and different that its true effectiveness is not accurately measured during a first analysis. It is possible that both novelty and disruption effects may operate in the same study and counterbalance each other. One way to measure the effects is to extend the treatment over a longer time. However, a another set of problems may develop if the effects caused changes in the skills or personological characteristics of the subjects. E) Pretest/Posttest sentiziation - 50