Tiramisu is good for you

advertisement

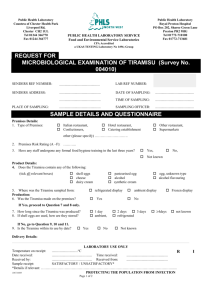

Epidem iol ogy EUROPEAN PROGRAMME FOR INTERVENTION EPIDEMIOLOGY TRAINING Mahon, Spain, 26 September – 15 October 2005 Tiramisu is good for you! Beer too! Exercise Case study based on an investigation conducted by Anja Hauri FETP / EPIET fellow, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, 2001 Case study prepared by Alain Moren, EPIET EPIET 2004. Major revision: 2005 1 Objectives At the end if the case study, participants should be able to: State hypothesis to be tested in a food borne outbreak Sort out the respective roles of several incriminated food items Select an appropriate control group among several options 2 Introduction: A school graduation ceremony where everything should have gone well On 26 June 1998 the St Sebastian High School in Stegen, Germany, celebrated the graduation from school by organising a party to which 250 to 350 participants were expected. Attendants included graduates from St Sebastian High School, their families and friends, teachers, 12th grade students and some graduates from the nearby Marie-Curie school of Kirchzarten. A self service party buffet was supplied by a commercial caterer from Freiburg. Food was prepared the day of the party and transported in a refrigerated van to the school. Festivities started with a dinner buffet open from 8.30 pm and followed by a dessert buffet offered from 10 pm. The party and the buffet extended late during the night and alcoholic beverages were quite popular. All agreed it was a party to be remembered. The alert On 2nd July 1998, the Freiburg Health office of the Federal Council Office of BreisgauHochschwarzwald reported to the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) in Berlin the occurrence of many cases of gastroenteritis following the graduation party described above. More than 100 cases were suspected among participants and some of them were admitted to nearby hospitals. Sick people suffered from fever, nausea, diarrhoea and vomiting lasting for several days. Most believed that the tiramisu consumed at dinner was responsible for their illness. Salmonella Enteritidis was isolated from 19 stool samples. The Freiburg health office sent a team to investigate the kitchen of the caterer. Food preparation procedures were reviewed. Food samples, except tiramisu (none was left over), were sent to the laboratory of Freiburg University. Microbiological analyses were performed on samples of the following: brown chocolate mousse, caramel cream, remoulade sauce, yoghurt dill sauce, and 10 raw eggs. The Freiburg health office requested help from the RKI in the investigation to assess the magnitude of the outbreak and identify potential vehicle(s) and risk factors for transmission in order to better control the outbreak. Cases were defined as any person attending the party at St Sebastian High School who suffered from diarrhoea (>= 3 loose stool for 24 hours) between 27 June and 6 July 1998; or who suffered from at least three of the following symptoms: vomiting, fever>= 38.5 ° C, nausea, abdominal pain, headache. Students from both schools attending the party were asked through phone interviews to provide names of persons who attended the party. Overall 291 responded to enquiries and 103 cases were identified (Attack rate = 35%). Among these cases, 84 received medical treatment and four were admitted to hospitals. Attack rates by age group were 36.6% for persons < 20 years, 32.1% for persons 20 to 29 years, and 36.8% for persons older than 29 years. 3 Most cases occurred between 27 and 29 June with an early peak from June 27, 0 am until June 28, 6 am. Figure 1 Cases of gastroenteritis by time of onset among attendees of a high school graduation ceremony (n=104), Germany, June 1998 Dessert-Buffet Number of cases 20 One case 15 10 5 0 1 Ju 2 ne 0 12 1. Ju ly 0 12 2. Ju ly 0 3. 12 Ju ly 0 12 4. Ju ly 0 12 5. Ju ly 0 12 6. Ju ly 0 12 30 . Ju ne 0 12 29 . Ju ne 0 12 28 . Ju ne 27 . 26 . Ju ne 0 12 0 Day/Month/Time in 6-hour-intervalls Q1. Summarise the above information and formulate hypotheses to be tested. 4 The shape of the epidemic curve, the attendance to a single event (a buffet) pointed towards a food borne outbreak related to a point common source of infection. Using the updated list of attendants, a retrospective cohort study including all attendants to the party (that could be reached) was conducted. All had received a standard questionnaire asking for demographic information, signs, symptoms and duration, admission to hospital, and food and beverages consumption at the party including amount consumed. Food specific attack rates were computed for more than 50 food items and beverages. Only those strongly associated to illness are shown in table I. Q2 Food and beverage specific attack rates are shown in table I. Identify potential vehicles and protective factors. Interpret the results Table I Food specific attack rates among attendants at a high school graduation ceremony, Germany, 26 June 1998, n=291 Eaten Not eaten Number ill Number not ill Attack rate (%) Number Number ill not ill Attack rate (%) RR 95%CI Tiramisu 94 27 77.7 7 158 4.2 18.5 8.8-38.0 Dark Mousse au Chocolat 76 37 67.3 26 148 14.9 4.8 3.1-6.6 White Mousse au Chocolat 49 23 68.1 49 156 23.9 2.8 2.1-3.8 Fruit Salad 46 25 64.8 53 159 25.0 2.6 1.9-3.5 Beer 30 74 28.8 67 95 41.4 0.7 0.6-1.0 Red Jelly 45 34 57 56 150 27 2.1 1.6-2.8 Vanilla Sauce 28 21 57 72 160 31 1.8 1.4-2.5 5 Several food items seem to play a role in the occurrence of illness; tiramisu, dark and white chocolate, fruit salad, red jelly and vanilla sauce. They can potentially explain up to respectively (94, 76, 49, 46, 45 and 28 of the 103 cases). Consumption of beer seems to play a protective role in the occurrence of gastroenteritis. Q3 Can we conclude that we had a multi-vehicle outbreak? How would you sort out the respective role of each food item? Draw relevant dummy tables. 6 In order to study the independent role of the consumption of fruit salad, dark and white chocolate, red jelly and vanilla sauce, the occurrence of gastroenteritis was studied among the group of attendants who did not eat tiramisu (Table II). Table II Food specific attack rates among attendees who did not eat tiramisu, high school graduation ceremony, Germany, 26 June 1998. Eaten Not eaten Number ill Number not ill Attack rate (%) Number ill Number not ill Attack rate (%) RR 95%CI Dark Mousse au Chocolat 5 17 23 2 139 1 16.0 3.3-77.6 White Mousse au Chocolat 4 13 24 3 141 2 11.3 2.8-46.3 Red Jelly 1 19 5 4 137 3 2.6 0.3-21.6 Vanilla sauce 1 13 7 4 141 3 2.6 0.3-21.6 Fruit salad 4 12 25 2 144 1 18.3 3.6-92.0 Q4 Interpret the results 7 Results presented in table II suggest that dark and white chocolate as well as fruit salad, red jelly and vanilla sauce consumption may have contributed to illness (since RR are high even among those who did not eat tiramisu). Such an association can be real (several contaminated food items, use of a single spoon to serve portions) or due to another unidentified confounding factor. Interpretation of results should also be cautious due to the small number of cases involved in this stratified analysis. 8 Part two In order to support the evidence that tiramisu was the main vehicle of the outbreak the investigators decided to study if a dose effect was present. The amount of tiramisu consumed was categorised as none, average or large. Q4 Using the following table, decide if the rate of illness varies with the amount of tiramisu consumed. Table III Cases of gastroenteritis among attendants at a high school graduation ceremony by amount of tiramisu consumed, Stegen, Germany, 1998 Tiramisu Total Cases Large Average None Unknown 56 65 158 12 50 44 7 2 Total 291 103 AR% RR 9 Part three From the crude analysis epidemiologists noticed that the occurrence of gastroenteritis was lower among those attendants who had drunk beer. They decided to assess if beer had a protective effect on occurrence of gastroenteritis. Q5 How would you go about testing that hypothesis? Q6 Develop any relevant table and calculate the relative risk. Interpret the results. You should use the following information: Number of those who drank beer, ate tiramisu and developed illness 27 Number of those who drank beer, did not eat tiramisu and developed illness 3 Number of those who did not drink beer, ate tiramisu and developed illness 63 Number of those who did not drink beer, did not eat tiramisu and developed illness 4 Number who did not drink beer but ate tiramisu 75 Number who did not drink beer 162 Number who drank beer 104 Number who ate tiramisu 116 Number who did not eat tiramisu 150 Unknown consumption of beer or tiramisu 25 10 By stratifying the analysis on tiramisu consumption we can measure the potential protective role of beer among those who ate tiramisu. The following tables show occurrence of gastroenteritis according to beer and tiramisu consumption. Table IV Cases of gastroenteritis among attendants at a high school graduation ceremony by beer and tiramisu consumption, Stegen, Germany, 1998. Tiramisu YES Beer YES Beer NO Total 41 75 Cases 27 63 AR 65.9 84.0 RR 0.8 Reference 95% CI 0.6-1.0 Total 63 87 Cases 3 4 AR 4.8 4.6 RR 1.0 Reference 95% CI 0.2-4.5 Tiramisu NO Beer YES Beer NO Q 7 Comment on the table above 11 It seems that consumption of beer may reduce the relative effect of tiramisu consumption on occurrence of gastroenteritis. The RR differ (0.8 vs 1.0) in the two strata. Effect modification may be present. This association between beer consumption and occurrence of gastroenteritis is however not confounded by Tiramisu consumption since the adjusted RR is 0.8 and the crude RR was 0.7 A similar stratification was conducted assessing dose response for tiramisu consumption among beer drinkers and not. Table V Cases of gastroenteritis among attendants at a high school graduation ceremony by beer and amount of tiramisu consumption, Stegen, Germany, 1998. Total Cases AR RR 95% CI __________________________________________________________________________ Tiramisu LARGE Beer YES Beer NO 19 34 17 30 89.5 88.2 1.0 0.8-1.2 Tiramisu AVERAGE Beer YES 22 Beer NO 41 10 33 45.5 80.5 0.6 0.4-0.9 Tiramisu NONE Beer YES Beer NO 3 4 4.8 4.6 1.0 0.2-4.5 Q7 63 87 Comment on the results 12 After stratifying beer consumption on the amount of tiramisu consumed, it appears that beer consumption reduces the relative effect of tiramisu on occurrence of gastroenteritis only among those who have eaten a average amount of tiramisu. This is suggesting that, if the amount of tiramisu is large, consumption of beer no longer reduces the risk of illness when eating tiramisu. 13 Part four During the investigation some epidemiologists considered that a lot of time and energy could have been saved by doing a case control study instead of a retrospective cohort study. They had proposed to do a case control study using the cases (here we will use the 101 cases for whom information on tiramisu consumption is available) and 1 control per case. Q8 How would you select controls? 14 In the following section of the case study we will illustrate the consequences of choosing controls from the original cohort or from non cases. Q9 Assuming you randomly select controls among non cases, and that controls are representative of exposure among non cases, complete the following table: Tiramisu Cases YES 94 NO 7 Total 101 Control OR 95% CI 101 Q10 Assuming you randomly select control among attendants to the party and that controls are representative of exposure in this group, complete the following table: Tiramisu Cases YES 94 Control OR 95% CI NO 7 ___________________________________________________________ Total Q11 101 101 Discuss the results obtained using the different sets of controls 15 The crude RR obtained after comparing AR between those who ate and did not eat tiramisu was 18.3 in the cohort study. The OR (76.9) obtained in the “case non-case” study (controls selected from the non cases group) overestimate the RR, because consumption of tiramisu is much lower (14.9 %) in the non cases group than in the entire source population (42.3%). Since controls should be representative of exposure in the source population, we should randomly select controls among the entire group attending the party rather than only among non cases. Anyhow the message is that when AR is high a cohort study is always preferred over any type of case control study. Q12 What other study design could have been chosen? References Rodriguez L and Kirkwood B: Case-control designs in the study of common diseases: updates on the demise of the rare disease assumption and the choice of sampling scheme for controls. Int J Epidemiol 1990; 19: 205-13 Rothman KJ: Epidemiology. An introduction. Oxford University Press2002. P 74ff 16 17