A PROGRAMME ON “TOOLS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL

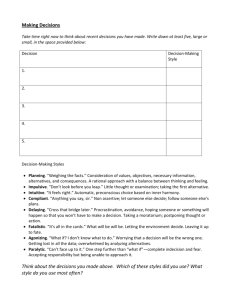

advertisement