Une classification économique propre au secteur de la culture

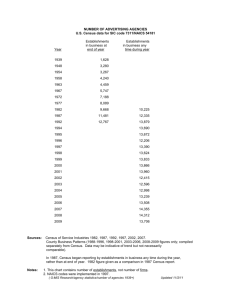

advertisement

An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience Christine Routhier, Research Officer Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec Institut de la statistique du Québec Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Workshop on the International Measurement of Culture Paris, December 4 & 5, 2006 An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 2 Introduction The Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec is pleased to participate in this workshop on the importance of the economic and social measurement of culture and would like to thank the OECD for the invitation. In 2003, the Observatoire developed a classification system for culture activities focusing specifically on the Québec context. The work involved in formulating such a classification was a relatively formidable task and this experience will be the subject of our lecture today. Above all, it may be helpful to mention that the Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec is a government agency which was created in 2000. The Observatoire is an integral part of the Institut de la statistique du Québec, the official statistical agency of the Government of Québec. The mandate of our agency is to produce and disseminate official statistics on the arts, media and culture in Québec, one of the Canadian provinces. The Observatoire was expressly created to meet the statistical needs of stakeholders involved in the different fields of culture and of the government agencies responsible for culture. The statistical work of the Observatoire deals with the culture markets, in other words the attendance rate at movie theatres, museums and live entertainments shows as well as the sale of books and sound recordings. The Observatoire also produces statistics on the profile of various types of cultural establishments or cultural workers, on the cultural consumption practices of Québeckers and on the cultural expenditures of the government. Our presentation will deal with the following items: 1. How the Observatoire circumscribed the sector of culture and communications. 2. What are the principal limits of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) in terms of culture and how does it justify the creation of a culture classification that is unique to the Observatoire? 3. Short description of our classification, the Québec Culture and Communications Activity Classification System (QCCACS). 4. Presentation of a few conceptual problems encountered during the development of QCCACS. 5. Examples of a few projects in which the Observatoire used QCCACS to produce statistics. 1. The perimeter of culture according to the Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec In the beginning, before undertaking its first statistical studies, the Observatoire had to explicitly describe and define the boundaries of its field of observation. The result of this reflection is recorded in a document which is available on our Web site1 and of which I will review the major points relating to the perimeter of the culture and communications sector. First, we decided to define culture and communications as an activity sector that is characterized by the production and dissemination of symbolic or information-based content. Then, we divided this sector into a dozen or so cultural fields: 1) visual arts, fine crafts, and media arts, 2) performing arts, 3) museums and heritage, 4) libraries, 5) books, 6) periodicals, 7) sound recording, 8) cinematography 1. OBSERVATOIRE DE LA CULTURE ET DES COMMUNICATIONS DU QUÉBEC (2002). Éléments d’un cadre conceptuel des statistiques de la culture et des communication, Québec, Institut de la statistique du Québec, 18 p. [Online:] http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/observatoire/classif_obs/cadre_concept_CM2002-02.pdf (French only) An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 3 and audiovisual, 9) radio and television, 10) multimedia, 11) architecture and design, 12) advertising, 13) public administration and associations. We had to make choices with respect to what we would include in the culture and communications sector and what we would exclude. For instance, we decided to include advertising, which is not a part of culture according to the European Commission’s2, Leadership Group on Cultural Statistics (LEG) but is included in Statistics Canada’s3 vision of culture. We also included multimedia (which roughly corresponds to what some call “new media”) and fashion design which is part of the field of “architecture and design”. As regards exclusions, let us of course mention the sector of environment and nature. However, museums, exhibition centres and interpretation centres focussing on natural and environmental sciences (for example zoos and botanical gardens) are considered a part of the cultural sector. Sports do not form a part of the culture and communications sector under the meaning of the Observatoire, even when there is an artistic component such as ice skating shows like Disney on Ice or the Ice Capades. Conversely, the televised broadcast of a hockey game is considered as a part of culture. It is important to mention that, for us, the term “communications” refers to mass media and that we therefore exclude telecommunication services such as telephone systems and Internet providers from this section, with the exception of enterprises engaged in cable distribution which we have included in the field of “radio and television”. 2. What was the purpose of creating the Québec Culture and Communications Activity Classification System (QCCACS)? Having defined the boundaries of our observation field, the next step consisted in organizing the observed world using a classification and nomenclature that gave direction to our statistical work. Within the sector of culture and communications, we needed to be able to categorize the types of activities (or establishments), the types of products and the professions. Understandably, the normal reflex was to turn to the classifications that were in effect in Canada. With regard to activities, this meant falling back on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), the standard classification used by Canada, the United States and Mexico. Unfortunately, it quickly came to light that NAICS did not meet the particular needs of Québec’s Observatoire. In fact, despite the level of refinement and efficiency attained by NAICS, we could only refer to it partially to organize the statistics on culture. That is how we were able to identify three major flaws in NAICS. Certain activity subsectors related to culture are absent from NAICS NAICS is divided into 20 sectors, two of which are specifically devoted to culture: 51 - Information and Cultural Industries; 71 - Arts, Entertainment and Recreation (which not only contains cultural industries but the entire entertainment industry as well). NAICS also contains several industries involving culture-oriented establishments outside these two sectors, for instance “45392 Art Dealers”, “45121 Book Stores and News Dealers” or even “54192 2. EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2000), Cultural statistics in the EU: final report of the LEG , Eurostat working papers, Eurostat population and social conditions 3/2000/E/No1, 200 p., (Luxembourg) 3. STATISTICS CANADA (2004). Canadian Framework for Culture Statistics, Ottawa, Culture Statistics Program, 35 p. [Online:] http://www.statcan.ca/bsolc/english/bsolc?catno=81-595-MIE2004021&ISSNOTE=1 An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 4 Photographic Services”. In fact, Statistics Canada designed a grid which groups all the NAICS industries that must be taken into account to produce cultural statistics3. However, NAICS does not describe some of the culture activities for which the Observatoire wishes to produce statistics. These cultural activities are not the subject of specific subsectors but are rather amalgamated with other economic activities. For instance, the notion of fine crafts does not exist in NAICS. In NAICS, establishments which produce goods are generally classified according to the materials used or to the types of products manufactured. No distinction is made between the size of these establishments or the way these goods are manufactured, namely whether they are manufactured industrially or handcrafted. For instance, a pottery artisan will be categorized under the same NAICS industry as a factory that manufactures porcelain sinks, namely “32711 Pottery, Ceramics and Plumbing Fixture Manufacturing”. Of course, all artisanal products are not necessarily fine crafts. Nonetheless, according to the way the economic data on production is organized under NAICS, it is impossible to calculate or estimate the value of fine crafts in Canada or in the province of Québec. Here is another example of a culture subsector that is not present in NAICS: the publishing of multimedia products such as video games or educational CD-ROMs. The multimedia industry is not the subject of a particular industry or subsector in NAICS. Establishments which specialize in multimedia are integrated into various industries, such as “51121 Software Publishers” or “54151 Computer Systems Design and Related Services”. Here, as well, it is impossible to find out the value of the multimedia industry from Canadian statistics4. Certain types of cultural establishments are engulfed in vast non-cultural industries As NAICS deals with the economy in general, it comprises industries that are relatively encompassing. However, to restrict oneself to the sector of culture and communications calls for a much more narrow approach, with smaller and more specific industries. For example, the Observatoire would be able to produce statistics on regional culture councils (in Québec, they are local non-governmental associations which promote the development of culture in a given region). In NAICS, however, regional culture councils would be lost in a vast industry such as “81331 Social Advocacy Organizations”. There are many more examples illustrating this particular lack of precision. For instance, agencies engaged in the research and development of museology and heritage are naturally not specifically identified in NAICS and fall under a large industry, namely “54172 Research and Development in the Social Sciences and Humanities”. For certain types of cultural establishments, no distinction is made in NAICS between the different fields of culture It is important to remember that the mandate of the Observatoire is to produce statistics required by the persons working in the different segments of culture in Québec: such as the visual arts, book publishing, cinematography, etc. On the other hand, some key categories of cultural establishments belong to industries that cross each other. This means that similar establishments form one single block, whether they belong to different cultural fields or not. For instance, industry “71151 Independent Artists, Writers and Performers” comprises a diversity of creators such as writers, actors, journalists and sculptors. Nevertheless, the Observatoire needs statistics on each of these types of creators, so it needs categories that are narrower in scope in order to identify them. 4. In order to solve this problem, the International Federation of Multimedia Associations has recommended that Statistics Canada identify the activities related to the multimedia industry in the next version of NAICS scheduled for 2007. An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 5 QCCACS objectives To put it briefly, NAICS did not attain the level of preciseness required for the culture and communications sector. Therefore, the Observatoire decided to create its own classification system and set five objectives to do so. 1. The classification needed to be sufficiently detailed to a) feature a large variety of economic activities within the culture and communications sector, and b) make it possible to cover each of the cultural fields while respecting their respective boundaries. 2. It had to reflect the Québec context and meet the particular needs of the Québec stakeholders in terms of culture. In Québec, the division of labour in the cultural field is understandably not the same as that in other societies; therefore a particular breakdown and nomenclature were needed to reflect the cultural reality of Québec. 3. It needed to emulate the classification work produced in other areas of the world (France, UNESCO, European Community, Canada) so our statistics could be compared with those of other societies. 4. As far as possible, we wanted to tie in our classification system with NAICS in order to be able to establish relationships with existing Canadian statistics and to link the cultural fields to the rest of the economy. This explains why some categories of the establishments defined by the Observatoire are a mirror image of the NAICS industries. 5. We also wanted to secure the approval of our main clients, namely associations representing the cultural communities of Québec. While designing our system, many questions were raised with respect to the logic used in establishing the rules of classification and of inclusion/exclusion, the nomenclature and the manner in which the definitions were formulated. At the outset, we had no idea of the various pitfalls we would encounter or of the difficulty in finding elegant solutions to all of these cases. Conceptually speaking, it was an undertaking that proved to be much more difficult than anticipated; for the objective was to create, on paper, a theoretical model which would represent a set of very diverse economic activities, at times unknown to each other, that we wanted to see as a whole. It is important to stress that some of the choices that we made were purely arbitrary. Some stray from logic but are based in tradition (for instance including cable distributors in the culture industry while excluding Internet providers) or based on the political and administrative structure of culture in Québec (the scope of action of the ministère de la Culture et des communications, the various grant programs, laws, etc.). Before expounding on some of the major conceptual problems that arose and on the solutions put forward by the Observatoire, I will give a brief description of our Québec Culture and Communications Activity Classification System (QCCACS). 3. Description of QCCACS Our classification system is presented in a body of work which can be downloaded from the Web site of the Observatoire5 free of charge. The various categories of establishments are divided into cultural fields and each establishment category has a specific name and is the subject of a definition. This work 5. OBSERVATOIRE DE LA CULTURE ET DES COMMUNICATIONS DU QUÉBEC (2003). Québec Culture and Communications Activity Classification System 2004, Québec, Institut de la statistique du Québec, 140 p. [Online:] http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/observatoire/publicat_obs/pdf/QCCACS04.pdf An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 6 also contains cross-reference tables between the 2002 NAICS and the 2004 QCCACS classification systems. We selected a classification structure that essentially uses the same logic as NAICS. As explained earlier, NAICS divided the economy into 20 “sectors”. Therefore, we decided to refer to the culture and communications field as a “sector” and divide this “sector” into 15 “fields”: 11 Visual Arts, Fine Crafts, and Media Arts 12 Performing Arts 13 Heritage, Museum Institutions, and Archives 14 Libraries 15 Books 16 Periodicals 17 Sound Recording (records) 18 Cinematography and Audiovisual 19 Radio and Television 20 Multimedia 21 Architecture and Design 22 Advertising and Public Relations 23 Organizations Dedicated to Representation and Advancement 24 Public Administration 90 Establishments involved in more than one field of culture and communications Each field is divided into a “group” corresponding to the different categories of cultural establishments that exist in Québec. Our “groups” are therefore the equivalent of what NAICS refers to as “industries”. Here is an example of a group and its definition: 18206 Dubbing Studios This group comprises establishments primarily engaged in providing dubbing services for films or television programs. Dubbing consists in substituting dialog from one language for dialog from another language. Exclusions: Sound Recording Studios (17203); Postproduction Studios and Other Services Related to the Production of Films and Television Programs (18205). We would like to stress that the term “establishment” includes self-employed workers. In fact, there are groups in QCCACS that are mainly composed of self-employed workers rather than of enterprises or agencies. This is reflected in the name of the group, for instance, “11101 Visual Artists” or “90109 Independent Journalists”. Independent workers are considered as the smallest form of establishment encountered in a given industry. In the culture and communications sector, they form a proportionally larger group than their counterparts working in the other sectors comprising the economy. The different types of establishments are classified in QCCACS according to their principal activity. It is the principal activity6 of a given establishment that will determine the field and the group under which it will be classified. Each group carries a name and a 7-digit code that is broken down as follows: Example: 11303.01, Contemporary Art Dealers 11303.01 11303.01 Field: Visual Arts, Fine Crafts, and Media Arts Function: Dissemination/Distribution 6. The principal activity is determined by a dollar value or in some cases by the number of assigned human resources. An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 11303.01 11303.01 7 Group: Art Dealers Subgroup7: Contemporary Art Dealers We adopted a practice developed by UNESCO which consists in identifying the types of cultural establishments according to their function in the production scheme. Generally speaking, culturalbased goods and services go through three stages before becoming available for public consumption: creation, production and dissemination. To this cycle is added the training function that groups establishments in charge of training persons working in the cultural sector. Therefore, within each of the 15 cultural fields, the various listed establishments are divided into four categories: creation, production, dissemination/ distribution and training.8 Some establishments carry out more than one function at once. This is the case of visual artists for whom the creation and production of their art work constitute the same activity or of certain theatre companies that assume both the production and presentation of their shows. These establishments are classified under one function or the other according to their principal activity or to the activity which constitutes their principal function or is at the top of their production scheme. Therefore visual artists will be classified under “creation” and theatre companies under “production” even though they also act as presenters. It is important to mention that our classification system was developed with the assistance of persons working in the different cultural fields described in QCCACS. This form of consultation was necessary to make sure that our categories of establishments adequately reflected the cultural reality of Québec. This exercise enabled us to better understand the inner workings of various cultural industries and the interaction between the different types of establishments which compose the book or film industry for instance. However, there was a second, more important reason that led us to consult the cultural communities: in the end, the statistics produced according to our classification system had to be recognized as pertinent by our major clients. By involving the associations from the cultural sector before the production of statistics and by securing their approval of the classifications, we avoided possible criticism. Certain choices, certain definitions as well as the exact name of certain groups were the subject of long debates with the representatives of the cultural communities who sit on the permanent advisory committees of the Observatoire. We, the Observatoire, were the guardians of logic and were deeply committed to respecting the objectives mentioned earlier while our colleagues from cultural-based associations had, at times, the need to defend economic or political interests through the classification. Nevertheless, we were able to reach a consensus in the end. 4. A few examples of the conceptual problems encountered while creating QCCACS The development of the classification system lasted a little over one year. During the course of development, many questions were raised, specifically with respect to the inclusion or exclusion of particular types of establishments that came to mind. For instance, we debated on whether QCCACS had to include stores that sold musical instruments and art materials. We finally decided to exclude them from the sphere of culture in order to include only the stores which sold cultural products, such as record stores, art galleries or book stores. Many questions were raised but for the purpose of this 7. The last two digits of the code indicate a subdivision within the group, but most QCCACS groups are not subdivided and end with “.00”. 8. Note that certain classification systems also feature a conservation function which the Observatoire has chosen not to include in QCCACS since all the establishments involved in conservation activities (museums, film libraries, archives, etc.) are already represented in field “13 Heritage, Museum Institutions, and Archives”. An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 8 presentation, I will hold myself to presenting the three basic problems that challenge the principles of economic classification. 4.1 The entities to be classified were occasionally only fragments of establishments In a classification system such as NAICS, the establishment is the basic unit of the classification 9 and we have applied this rule to our system in most cases. However, some cultural-based activities are in fact not whole establishments per se but fragments of non-cultural establishments. For instance, graphic design services (a cultural activity) can be found within non-cultural enterprises such as automobile manufacturers or supermarket chains. Of course, it was not pertinent for us to accept every type of fragment forming an establishment that could engage in cultural activities in QCCACS. For instance, as regards graphic design services, only specialized agencies are considered while graphic design units that are integrated to other establishments are not. It was, however, necessary for QCCACS to be able to include certain types of these fragments that form establishments. For instance, within group “14401 Educational and Training Institutions Related to the Field of Libraries”, we will find universities that offer training in library science and information science, for example the Université de Montréal. Nevertheless, it is not the Université de Montréal (establishment) as a whole that interests QCCACS, but only the library science program. The definition of this group is as follows: This group comprises public and private educational institutions primarily engaged in providing terminal instruction and training in the field of libraries. This group includes C.E.G.E.P., university, and other general education programs aiming to train graduates who will work specifically in the field of libraries. Contrary to NAICS, the entities listed in our classification system are not always establishments per se, in certain cases they are only fragments of establishments. 4.2 Certain types of establishments did not belong to a particular cultural field As seen earlier, the first hierarchical level of subdivision within our classification system is the cultural field, a subdivision which seems both logical and natural. Unfortunately, certain types of cultural establishments have an interest in more than one field at one time while others have an interest in the entire sector of culture and communications. Such is the case of actors10, who can work at any given time in the fields of cinematography, television, the performing arts, multimedia and/or advertising. Superstore retailers, such as FNAC or Virgin Megastore, which sell cultural products, are also interested in more than one cultural field: they sell books, sound recordings, periodicals, motion picture DVD-ROMs and video games. Another example: municipal cultural centres that present exhibits, shows and film projections. It is impossible for these cultural establishments to determine one field of principal activity. This situation was problematical because, obviously, the cultural fields featured in our classification had to be mutually exclusive. No establishment group could be classified under two different cultural fields. That is why we created an additional field that was used to group these “multi-field” establishments that are active in more than one field at one time. It is not a cultural field per se because it does not truly exist. It carries code 90 to separate it from the other genuine fields which have codes ranging from 11 to 24. 9. An establishment is defined as a unit of observation that provides, at the very least, the accounting data required to measure production but not a complete set of financial statements (as is the case of an enterprise). 10. It is important to remember that actors, as independent workers, are considered as establishments. An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 9 The addition of field 90 strays somewhat from the logic and the precept of principal activity which must normally indicate the field and the group under which an establishment is classified. The fact that many establishment groups are “exiled” to field 90 does present another disadvantage. If we study the list of establishment types featured in a given sector of the classification system, for instance the section devoted to books, we will not get an exhaustive list of all persons involved in the field of books: the “multi-field” establishments are missing, namely writers and illustrators. To address this problem, we added a note at the end of each section that reads as follows: The following groups are also considered in the analysis of the field of books: 90107 Authors of Books or Periodicals 90107.01 Writers 90107.02 Other Independent Authors of Books or Periodicals 90108 Independent Translators 90110 Independent Illustrators 90111 Independent Graphic Designers and Computer Graphics Designers 90112 Independent Photographers in Communication 90301 Superstore Retailers – Cultural Products 90304 Other Points of Sale – Cultural Products 4.3 Certain types of establishments cut across two cultural fields without being “multi-field” Another problem associated with cultural fields is that certain types of establishments are ambiguous in nature. These establishments engage in activities that cut across two cultural fields but are not, for all that, a “multi-field” establishment. For instance, we asked ourselves with which cultural field we should associate establishments that publish virtual periodicals, for example a magazine that is exclusively released on the Internet, like Wired magazine. Do these establishments belong to the field of periodicals or of multimedia11? Which one should take precedence over the other, the medium or the nature of the work in which the establishment is engaged? Generally speaking, when dealing with establishments that produce goods, it is the medium that indicates the field to which they belong. Thus, an establishment that produces advertising films will be classified under the cinematography and audiovisual field and an establishment that publishes sheet music will be classified under the field of books. Nevertheless, we decided that publishers of virtual periodicals did not belong to the multimedia field as the rule of medium would prescribe, but to the field of periodicals since the work of these establishments is much more similar to that of establishments which publish printed periodicals. It is important to note, however, that as Internet practices evolve rapidly, we can ask ourselves if the publishing work involved in producing an electronic periodical is still as similar today to that of a printed periodical. We would like to stress that in the chapter devoted to multimedia, we explicitly mention the exclusion of virtual periodicals while adding a note to the effect that virtual periodicals may be entered under field 20 (Multimedia) for statistical survey purposes. There are other cases where the field of classification is not dictated by the product’s medium, such is the case of artists who create art works related to the media arts. These art works are often presented on a multimedia vehicle, such as a Web site or a CD-ROM, but we classified these establishments under the visual arts, in field 11 “Visual Arts, Fine Crafts, and Media Arts”. Here, it is the artistic nature of the products and their status as works of art that supersede the medium principle. In the field, 11. We defined the multimedia product as a “digital document that is interactive and features more than one medium (text, sound, still, or animated images) on one support”. Moreover, we only included the establishments that make products featuring documentary, cultural, educational, or play-oriented content into the multimedia field. Thus, an enterprise that publishes a telephone directory for the Internet is not part of the multimedia field under the meaning of the Observatoire. (No more than a publisher of printed telephone directories can be part of the field of books.) An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 10 persons practicing the media arts interact as much with the multimedia world and the cinematographic world as they do with the visual arts world, but we were under the impression that their motivations were certainly more similar to those of visual arts creators. The two ambiguous examples that I just mentioned question what we commonly refer to as “new technologies”. This is not surprising as all innovations are susceptible of raising classification questions and of drawing attention to the nearly permanent obsolescence of classificatory systems. Thus, some questions were not raised in 2003 when we developed QCCACS but will be raised when we revise it in order to release a new version. Can blogs from journalists be considered as a medium? If so, should we create a specific group for them or simply mention them in the definition of an existing group? To which field would they belong? To the field of periodicals or of multimedia? Should we replace the “multimedia” field by a field that we would call “new media” and which could include Web-enabled radio and television? These were examples of problems that can arise when we attempt to create a classificatory model, which is necessarily rigid and reductive in nature. The objective is to perfectly meld various types of “culture-oriented” establishments, which will form, in the end, a logical and consistent whole. However, in reality, there are crossovers or solitary islands and in trying to put all the pieces of the puzzle together, we come up against the need to create categories whose boundaries are somewhat irregular or unusual. 5. A few examples on how QCCACS is applied in the field To conclude, I will briefly go over a few projects of the Observatoire in which we used the QCCACS system. As you will see, even though it is necessary for a statistical production agency to refer to a theoretical model such as a classification system, in practice, projects are not always an exact copy of the previously defined categories. The secondary activity phenomenon When we conduct a survey of a given type of cultural activity, one of the stages consists in drawing up a list of the establishments which constitute the population being studied. However, we often need to survey not only the establishments of which it is a principal activity, but those of which it is the secondary activity as well. For instance, in a survey of archival services, we questioned not only the institution expressly devoted to the conservation of archives, but also all types of agencies and enterprises (for example an aluminium manufacturer) that possessed historical archives that were open to the public. The principal activity of these establishments is not the conservation of archives; to them it is a secondary activity. In point of fact, their principal activity has nothing to do with culture. Nevertheless, we must definitely include them in our survey population because the role that they play with respect to heritage is important. Therefore, we do enter them in our data base on cultural establishments, but we cannot assign a QCCACS code to them as they fall beyond the limits of culture. We can, however, assign them a secondary activity code from QCCACS. The possibility of assigning a secondary activity code does not only pertain to establishments that fall beyond the scope of QCCACS, it also pertains to cultural establishments. Thus, a museum (code 13203) could have a secondary activity code if it also presented live entertainment shows (code 12302) and we would have to include it in our survey of the attendance rate at live entertainment shows. An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 11 The obsolescence of classifications When we put together a statistical survey, we may observe a few discrepancies between a classification system such as QCCACS and reality. Thus, it may be necessary to survey new types of establishments that are absent from the classification (such as blogs from journalists mentioned earlier) and may conversely realize that certain QCCACS groups are in fact unnecessary. This is the case of one group part of the field of books “15301 Sheet Music Retailers”. In reality, the number of establishments who engage in this principal activity are exceptionally few (less than 10 in Québec) because usually they are retailers of musical instruments or sound recordings or even music schools which sell scores. Establishments whose principal activity consists in selling scores should have been integrated in a catchall category such as “15910 Establishments Related to the Field of Books n.o.c.”, in order to avoid weighing down the QCCACS system unnecessarily. Ideally, all classification systems should have a rule regarding the minimum number of establishments engaged in a certain activity before assigning them to a specific group. But in reality, it is only at the moment of launching a survey, thus of drawing up the list of the establishments to survey, that we discover the size of the group. In the beginning, at the time we were developing QCCACS, the Observatoire only had a scattering of data on certain types of establishments. However, when comes the time to release a new version of QCCACS, some groups may be eliminated, such as “15301 Sheet Music Retailers”. The need to operationalize certain concepts As amazing at it may seem, it would be best for certain concepts on which we rely to define types of cultural establishments not to be explained within the text of the classification system. Such is the case of the concept of “professional” establishments. This concept played a central role in a survey of the socioeconomic profile of writers that the Observatoire conducted in partnership with the Bibliothèque nationale du Québec and the Union des écrivains québécois. For this purpose, we would like to call to mind the definition of writers in QCCACS: This subgroup comprises professional authors of books or periodicals primarily engaged in creating, on an independent basis, literary works (…). These works include stories, novels, short stories, tales, plays, poems, and essays. Writers whose works have been published by a recognized publisher are considered as professional writers. In order to limit the population targeted by the survey, this definition was narrowed down so as to include only a portion of writers: those who had at least one work published during the past 10 years and at least two works published during the course of their career by a recognized publisher. This was done because our partners in the project wanted the profile to apply to writers who were considered as “professionals” under the criteria of the Union des écrivains québécois. It is important to know that most QCCACS groups which involve independent workers (actors, dramatic authors, producers, journalists, etc.) mention that they are professionals but this notion is seldom indicated explicitly. It is only when “in the field” and using objective criteria that we will attempt to operationalize the concept of “professional”. These criteria are susceptible of changing according to the legal, administrative and economic context and to the specific objectives of each project. Therefore, it is wise that a classification system such as QCCACS refrain from defining certain concepts, which may be extremely important, but which have a changing character. An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 12 Defining the boundaries of the survey world Within the scope of a survey of establishments specialized in multimedia production, the Observatoire had as a partner, Alliance numériQC, an association of enterprises and agencies active in the field of multimedia. However, the population from which our partner wished to obtain the profile did not limit itself to the establishments of group “20201 Multimedia Producers”, whose definition is: This group comprises establishments primarily engaged in assuming (…) the responsibility and eventually the financing of multimedia projects featuring documentary, cultural, educational, or play-oriented content (…). These establishments produce multimedia projects that my be presented in the form of CD-ROMs, Internet sites, computer games, training software, DVDROMs, interactive terminals, etc. In so doing, they orchestrate the different activities relating to the design, development, and distribution of these products. In fact, the interest of our partner went beyond the scope of what we had defined as cultural multimedia, namely the products featuring “a documentary, cultural, educational, or play-oriented content”. Moreover, it was not only the producing establishments which interested our partner, but all establishments which engaged in multimedia production as a principal activity. At the time of the survey, we started by drawing up a list of all establishments known to be active in the field of multimedia in Québec and we then contacted all of these establishments to ask them if they showed the characteristics of the establishments whose profile we wanted to outline. To be considered as “specialized in multimedia production”, an establishment had to have, as a principal activity, one or several of the three types of activities listed below: Creation/ideation, development, or publishing for the purpose of producing multimedia products. Offer support services for the production of multimedia products, for example, scripting/ideation, programming, computer graphics, animation, digitization, sound/image processing, integration, etc. Create Web sites for other organizations or enterprises. Thus, you may notice that in order to define an “establishment specialized in multimedia production” under the meaning of the survey, we did not refer to the types of establishments listed in QCCACS, namely: 20101 Independent Designers and Script Writers in Multimedia 20102 Independent Art Directors in Multimedia 20103 Other Independent Creators in Multimedia 20201 Multimedia Producers 20202 Independent Project Managers in Multimedia Instead, we singled out, here and there, among the definitions of these different groups, the activities which interested our partner. We did not restrict the participation criteria by invoking the fact that the multimedia products had to have a documentary, cultural, educational or play-oriented content as defined in QCCACS. Within the framework of this survey, the multimedia products could also contain advertising or commercial content. In short, we only kept the definition of “multimedia” and the concept of principal activity as presented in QCCACS. What is more, we accepted to conduct a survey that went beyond the borders of culture as the goal was to find a broad range of multimedia production activities, of which some were not culture-oriented under the meaning of the Observatoire. At the conclusion of this project, we published statistics on what we referred to as a set of “establishments specialized in multimedia production”, but this set does not exist per se in QCCACS. Obviously, this is a case of non-correspondence between the QCCACS classification and the published statistics, even though QCCACS was designed expressly to define the entities for which statistics An Economic Classification for the Culture Sector: the Québec Experience 13 would be produced. One should not come to the conclusion that the field of multimedia was inadequately defined in QCCACS (all the more so since Alliance numériQC was also our point of contact when we designed the QCCACS chapter devoted to multimedia). What we could conclude, though, is that in an industry as young as multimedia, statistical needs are difficult to anticipate from the outset. Conclusion The experience of the Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec gives us an insight into the difficulties that can arise in the description and the organization of cultural activities within a classification system that is expressly devoted to them. In the light of this experience, we can easily understand that between three classification systems that do not specifically deal with culture but with the economy as a whole, namely NACE12, ISIC13 and NAICS, we may observe, for the same type of cultural activity, a categorization that is oftentimes not comparable. Thus, as the OECD explained in its orientation paper14, it is according to these three international classifications that most countries produce their cultural statistics and the major differences that they present, added to the fact that some of their categories can encompass both cultural and non-cultural fields, constitute a major difficulty for the project on the international measurement of culture. On account of this difficulty, we find ourselves without any option but to calculate estimates in order to determine the economic value of a given cultural activity. To lessen the impact of the non-concordance of classifications and the possible inaccuracy of estimates, one of the solutions could be to confine the OECD project to the fields of activities that constitute the “solid core” of culture: namely publishing, cinematography, the performing arts, the visual arts, museums, media, etc. In other words, the OECD could possibly exclude the activities regarded as the outlying areas of the culture sector, such as advertising, architecture, printing, design and multimedia. 12. Nomenclature statistique des activités économiques dans la Communauté européenne. 13. International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities. 14. Gordon, John and Beilby-Orrin, Helen (2006). International Measurement of the Economic and Social Importance of Culture, Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Statistic Directorate, August, 99 p. [Online:] http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/26/51/37257281.pdf