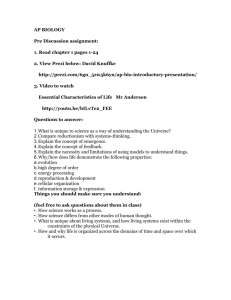

Cosmological Arguments for the Existence of God:

advertisement

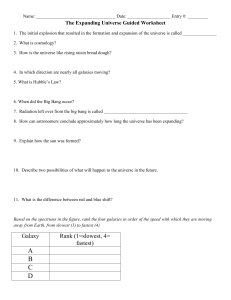

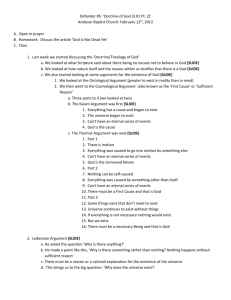

Cosmological Arguments for the Existence of God: An Introduction Jonathan Webber `Cosmological' is a name given to a group of arguments for the existence of God, or some other underlying cause of the universe, which are based on the simple fact that there is a universe. Such arguments, in various forms, have been advanced by many of the great figures in the history of thought (such as Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas and Leibniz), and attacked by many other great figures in the history of thought (such as Hume, Kant, Mill and Russell). Given this, it is hardly surprising that the debate is complex and, at first, rather opaque. The aim of this article is to introduce the reader to this debate through a discussion of some of the key issues surrounding the three most popular forms of the argument: [A] The kalam argument. Everything that has a beginning has a cause. Since the universe had a beginning, the universe was caused. Since a cause must be distinct from its effect, the universe must have been caused by a non-physical entity. [B] The `chain of causes' argument. Every event is caused by some previous event, which is itself caused. There is, therefore, a chain of causes. This chain of causes must have its origins in a First Cause, an efficient cause of the rest of the chain, which is not itself caused. [C] The argument from contingency. Events in the universe are contingent (i.e., they need not have occurred). A contingent event occurs only if it is caused to occur. There is, therefore, a chain of causes which must have its origins in a necessary being/event (i.e., one that could not have not existed/occurred). Only God is necessary. Problems of Causation All three of the above arguments attempt to show that the universe itself has a cause. There are three related objections to such a suggestion. David Hume (1711-1776) claimed that the idea that event-type C causes event-type E arises from human observation of `constant conjunction' of Cs and Es. That is, if I observe that E follows immediately from C - every time that C occurs - I come to the conclusion that there is some `necessary connexion' between the two events, some invisible force due to which an event of the type E must follow an event of the type C. If Hume is right, it is justifiable to infer a causal connection between two events only after observing repeated instances of their conjunction. If this is so, it would be justifiable to infer a cause of the universe only if other universes had all been observed to follow from some event or agency. Since this is not possible, there can be no inferences made about a cause of the universe. A similar objection to the claim that the universe itself may have a cause, or that the chain of causation may be rooted ultimately outside the universe, is given by Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781). Kant argues that since the concept of causation arises within the spatio-temporal world of experience, it is confined to the observable world, so to talk of causation outside of that realm `has no meaning whatsoever'. A different experiential objection is raised by John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), in his article `Theism'. Mill claims that since our experience teaches us that all events are caused by antecedent events, a cause that was not itself caused cannot be hypothesised; `Our experience, instead of furnishing an argument for a first cause, is repugnant to it.' There are, of course, difficulties with the understandings of causation on which the above objections are based, but it would be a digression to assess this question here. However, there is a serious conceptual difficulty with rejecting the notion of a cause of the universe: to do so is implicitly to reject the `principle of sufficient reason'. This is the principle, proposed by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), that nothing is the way it is without a sufficient reason for being so. Leibniz's principle is a refinement of the ancient metaphysical thesis `ex nihilo nihil fit' (of nothing, nothing comes) - or, in the words of Shakespeare: `Nothing will come of nothing' (King Lear I.i). The whole history of science has been a gradual realisation that things do not `just happen', but constitute a subtle and intricate interrelation of events. The history of science, therefore, has presumed and somewhat vindicated a principle similar to that proposed by Leibniz. To reject the idea that there is an ultimate cause of the universe is implicitly to reject the principle of sufficient reason: something will have come from nothing. It may be argued that the existence of the universe does not necessarily imply a first cause, since there could be an infinite chain of causes. To argument [C], this is the objection that every contingent event may simply be due to another contingent event ad infinitum, so there need be no ultimate cause, no necessary event or being. To arguments [A] and [B], on the other hand, this is the objection that the causal chains within the universe may have an infinite history and, as such, the universe itself has no beginning and, therefore, no ultimate cause. The Question of Time The idea that the universe has always existed is philosophically problematic: if history is infinite in length, not only do we have to claim that infinitude has already occurred, but also have to agree that as time continues to pass and new events join history, infinity is being added to. St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) rejected the notion of infinite history as impossible since, he claimed, if there were no first cause, no subsequent causes would ever come into being. That is, if the series had no beginning, how does it come about that the sequence occurs at all? The currently dominant scientific account of the history of the universe, the `big-bang' theory, seems to imply that the universe does not have an infinite history. This is the theory that the universe began as one exceedingly dense, infinitely hot, concentration of neutrons (the `primeval nucleus'), which exploded. As time went on, the neutrons began to clump together forming the first `heavy hydrogen' nuclei. This process of expansion and therefore cooling and structure-formation has resulted in the universe as it is today, and is continuing. There are three major pieces of evidence in favour of this theory. Firstly, it was claimed in 1948 that if the big bang theory is correct, there would still be traces of radiation from the initial explosion at a temperature little above `absolute zero' (273 degrees C). In 1965, this radiation was shown to exist. Secondly, calculations of the relative amounts of various elements in the universe, based on the big bang theory, accord well with observations of the universe. Thirdly, there is (at present) no way of accounting for the inordinate amount of helium in the universe other than the big bang theory. However, in his A Brief History of Time (1988), Stephen Hawking offers an alternative view: the model of space-time curvature. Hawking proposes that the four dimensions of space and time are considered as together forming a `surface' which is finite in size, but has no beginning or end - similar to the surface of a sphere. Hawking insists that this `is just a proposal: it cannot be deduced from some other principle'. In conjunction with quantum mechanics, this theory can explain all the complex structures in the universe. The existence of quasars, on the other hand, presents a difficulty for Hawking: quasars (or `radio-stars') are thought to represent past explosions, and therefore seem to imply some sort of instantaneous `big bang' beginning. However, this objection is not very strong: if quasars do not represent past explosions, they provide no evidence against Hawking's theory. This understanding of space and time has serious ramifications for versions [A] and [B] of the cosmological argument. As Hawking points out: `If the universe is really completely self-contained, having no boundary or edge, it would have neither beginning nor end. What place, then, for a creator?' The Question of Contingency Cosmological arguments of the form [C], above, cannot fall foul of the idea that the universe may have had no beginning, since they attempt to argue not that the history of the universe was begun by Divine activity, but that the universe exists only because God causes it to. If Hawking's model of space-time curvature is a correct understanding of the universe, arguments [A] and [B] lose their common presumption - that the universe began. However, argument [C] is untouched by Hawking's theory: why does a spatiotemporally boundless universe exist? Where scientists attempt to understand the `laws of nature', arguments such as [C] ask why those laws hold. Argument [C] rests on the idea that the universe exists contingently. That is, it may be true that the universe is composed of energy-matter consisting in space-time and exhibiting certain qualities and tendencies, but it is only contingently true: science can give no ultimate reason why the universe is the way it is, or indeed why it is at all. The universe could have been different; the universe need never have been. Given the `principle of sufficient reason', everything that occurs does so for a reason - things do not `just happen'. A contingent event is an event which need not have occurred. A contingent event, therefore, occurs only when there is a reason for its occurrence. If it is contingent, then it must also have a reason for occurring. Ultimately, therefore, the universe exists due to some necessary being or event, which does not itself have a reason for being. The central difficulty with this argument concerns its use of the concepts of necessity and contingency, usually considered to refer to the connection between a subject and a predicate, but here used to pick out a mode of existence. (For example, the subject `triangle' has the necessary predicate `has three sides', but it may also have the contingent predicate `is drawn in red ink'.) Hume insists that matters of fact (i.e., claims that certain things exist) and relations of ideas (such as predication) are entirely separate and cannot be combined. On the Humean view, then, there cannot be necessary existence or contingent existence, since necessity and contingency are relations of ideas, where existence is a matter of fact. To talk of necessary or contingent existence, on this view, is as much a category error as the statement: `this idea is yellow'. Kant offers another reason why existence cannot be necessary: necessity is a relation between a subject and a predicate, but existence is not a predicate. To say that x exists, according to Kant, is to say that there is a thing which corresponds to my concept of x. If existence is a predicate, then an existing thing (e.g., a horse) can never correspond precisely with the concept of it (e.g., the concept of a horse) - for the concept does not have the property of existence. Gottlob Frege (1848-1925) held a similar theory: to say that x exists, according to Frege, is to say that the number of mind-independent objects that correspond to the concept of x exceeds zero. That is, `x exists' means not that x has the property of existence, but that there is at least one thing that corresponds to the concept x. The logical claims of Hume, Kant and Frege are subject to debate, but it would be a digression to discuss them further here. This is because Hume, Kant and Frege are all discussing logical necessity - necessity as a relation between concepts. It has been claimed that logical necessity is not the only kind of necessity; that a thing can be `necessary' (in the sense that it could neither be other than it is, nor not be at all) without being logically necessary. For example, both Aristotle and Aquinas refer to eternal truths as `necessary', and Kant talks of `factual necessity' - the necessity of the laws of nature. God has often been characterised as self-dependent. If God is omnipotent, incorruptible, and indestructible, then it seems that God simply is and cannot not be. There cannot have been an event in the past that brought God into existence, and there cannot be any event that would bring it about that God ceases to exist (since either of these would limit the power of God). This understanding of the nature of God renders God necessary in the sense of entirely independent of any conditions: since no situation would be God-less, God cannot not be. This understanding of God can be expressed in terms of Aquinas's view that God's existence is identical with God's essence, or in terms of the view, proposed by Paul Tillich (1886-1965), of God as `Being-itself'. Most recently, this view has been advanced by John Hick, who talks of God's existence as one of aseity (i.e., God is independent of all that is not God). If God is seen in this way, God's existence can be understood as necessary in contrast with the contingent (i.e., superfluous, dependent) existence of the universe and all its contents. Such a view of necessary and contingent existence ties in well with cosmological arguments of type [C]. Theological Difficulties There are two major theological difficulties with cosmological arguments. To begin with, the argument need not conclude in theism, since deism would suffice. Where theists claim that God is continually involved in the universe, deists claim that God created the universe and left it to obey its own laws. The cosmological argument concludes only that God created the universe. In A Brief History of Time, Hawking writes: With the success of scientific theories in describing events, most people have come to believe that God allows the universe to evolve according to a set of laws and does not intervene in the universe to break those laws. However, the laws do not tell us what the universe should have looked like when it started - it would still be up to God to wind up the clockwork and choose how to start it off. So long as the universe had a beginning, we could suppose it had a creator. However, theists may counter-argue that the cosmological argument, if it is sound, can be used to prove also that God sustains the universe in existence. That is, if the question `Why did the universe start?' is replaced with `Why doesn't the universe stop?', a cosmological argument may be formulated which will conclude that the universe continues to exist due to a Divine cause. The second theological objection concerns the cosmological arguments' characterisation of God. Argument [A] characterises God as the cause of the universe; argument [B] characterises God as the cause of all events; argument C characterises God as a necessary existent, cause of all contingent beings. Cosmological arguments do not lead to the traditional Western understanding of God as an all-powerful, personal moral authority. However, it may be argued that the understanding of God as creator is part of the traditional understanding and does not contradict any of the other traditional divine attributes; if you can see a long grey trunk protruding from the bushes, there is probably an elephant attached. Key Terms Aseity - To exist a se is to exist independently of any conditions. My existence, for example, is not a se since there are conditions required for it (e.g., the presence of oxygen). Contingency - The opposite of necessity (see below). That John Major is Prime Minister, for example, is contingent. Necessity - A thing is said to be `necessary' if it cannot be other than it is. That 2 plus 2 equals 4 is necessarily true, since two plus two could not equal anything else. Predicate - In Aristotelian logic, a predicate is something that is affirmed or denied of a subject. For example, in the sentence `Plato is a philosopher', the subject is `Plato' and the predicate is `being a philosopher'. Suggested Reading For a general survey of the issues surrounding cosmological arguments, see: Brian Davies, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion, Rev. ed. (OUP, 1993), Chapter 5. For more detailed analysis, see: J.L. Mackie, The Miracle of Theism: Arguments for and against the existence of God (Clarendon, 1982), Chapter 5. Richard Swinburne, The Existence of God. Rev. ed. (Clarendon, 1991), Chapter 7. For a discussion of the history of the universe, see: Stephen W. Hawking, A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes (Bantam, 1988), Chapter 8. For a discussion of necessary and contingent existence, see: R.M. Adams, The Virtue of Faith (OUP, 1987), Chapters 13 and 14. J. Hick, God and the Universe of Faiths (Macmillan, 1988), Chapter 6.