Pakistan Earthquake

advertisement

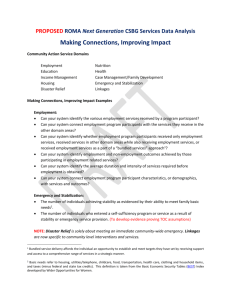

1 Bernadette White Power and Relief: Foucault Applied to the 2005 Pakistan Earthquake Relief Effort In the early hours of October 8, 2005, a 7.6 magnitude earthquake rocked the remote areas of Pakistan’s Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP) and Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK). The quake affected over 4,000 villages, left 73,000 people dead, and another 79,000 injured. With 3.3 million people left homeless and winter soon to arrive, the need for aid and relief was critical. Power and power relations were a major part of all interactions in the Pakistani relief efforts. This paper applies Michel Foucault’s theories of power to the relief efforts and actions of the Pakistani government in the wake of the 2005 earthquake and suggests recommendations to ameliorate future relief efforts in the region. Particular focus will be given to the groups that the government allowed to operate freely in the region and the leadership role the military took in directing the relief efforts and how its actions relate to the exercise of power. Equally important, this paper will also focus on the role of jihadi groups and the impact their role in relief efforts has had in the affected areas, as well as the means by which they exercised power in contrast to the Pakistani government. In the wake of the disaster certain international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and several other civilian organizations, based in urban centers of Pakistan, rushed to provide aid to areas affected by the earthquake. The Pakistani government hindered these organizations, allowing Jihadi groups to be among the first, besides the government, to provide assistance in the affected regions (McGirk 2005, 2). The Pakistani military regime under General and President Pervez Musharaff took the lead in the rescue efforts. Simultaneously, the Pakistani army rushed to secure bases and outposts that had been destroyed by the earthquake near the Line of Control, 2 the default boundary between India and Pakistan in Kashmir, although nearly a quarter of a million soldiers were already in the disputed region. This diversion of military resources slowed aid delivery to earthquake victims for several days (McGirk 2005, 1). The rugged geography of the affected areas and the presence of poorly housed Kashmiri refugees compounded the difficulties of coordinating the relief effort, particularly in AJK. The Pakistani government established the Federal Relief Commission (FRC) and the Earthquake Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Authority (ERRA) to act as a liaison between the government and international, as well as national, aid organizations (International Crisis Group 2006, 4). Prior to the earthquake the Pakistani government reduced many civil services in the region, claiming civilian authority had collapsed (International Crisis Group 2006, 4). Local government officials, therefore, were not well positioned to aid in the massive effort to provide relief after the earthquake. Efforts were instead shouldered by the military, rather than shared with local entities. In addition, no detailed plans for disaster response existed, even though the area is prone to natural disasters. Instead of maintaining civilian institutions, there has been a disproportionate buildup of the army and even the build up of the army lacked the professional management development necessary in disaster relief efforts (McGirk 2005, 2). Overall, the FRC acted as a means to institutionalize the military’s role in coordinating relief efforts (International Crisis Group 2006, 3). The ERRA is part of the prime minister’s secretariat, and therefore, is under the control of the military (International Crisis Group 2006, 5). The creation of the ERRA was widely criticized by the United Nations and other international organizations, but given the humanitarian crisis, their criticism found little traction. The state of emergency gave the Pakistani government the ability to exercise its power freely, under the aegis of a state of emergency and need for control. 3 One disturbing trend in the relief efforts, with serious implications for the security of the region is the inclusion of jihadi groups in the relief efforts. Pakistan has over 58 religious groups, of which 24 are known militant groups, making it difficult to differentiate groups with a missionary purpose from those political groups that espouse violence. In the Kashmir and NWFP regions, the Jamaiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) and the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI), two of the most prominent religious parties, are major partners in the Mattaia Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) alliance, a political coalition known for its radical politics. JUI and JI are two of the most prominent religious parties and are active participants in local jihads in Kashmir and Afghanistan. Two prominent jihadi groups, the Lashkhar-e-Toiba (LeT) and the Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) were also active in relief efforts, under the name of front organizations (International Crisis Group 2006, 9). Of the Islamist organizations involved in the relief efforts, they can be divided into party-affiliated organizations and front organizations for jihadi groups. Some of these groups were not present or known in the affected areas before the earthquake. The earthquake enabled these entities to establish a presence through provision of aid (International Crisis Group 2006, 10). This provided an opportunity for these organizations to recruit new members and gain a presence in a region that has historically experienced great political unrest. New Humanitarianism—Imposition from Outside Humanitarian relief efforts have always been highly political. In most cases, aid is used as a means, particularly by Western governments, to transform conflicts, decrease violence and set the stage for development (Duffield, Macrae, & Curtis 2001, 269). Due to globalization, UN agencies, NGOs and private companies have been able to exercise influence over the internal affairs of states in areas that are considered “the global borderlands” (Duffield 2001, 309). This 4 phenomenon has become known as the “new humanitarianism.” The actions taken by the Pakistani government aimed to limit the influence of these Western organizations. However, the government acted in a similar fashion to Western organizations in AJK and the NWFP; the relief efforts became a political opportunity exploited by the military government to gain a foothold in the most remote regions of Pakistan (International Crisis Group 2006, 4). Another aspect of traditional humanitarianism that developed differently in Pakistan, due to the authoritarian government’s conduct and coordination of relief efforts, are how the underlying concepts of neutrality, impartiality, independence, and universality were regarded. The principle of universality connotes that aid will get to all victims, regardless of where they live, and impartiality implies that aid is given to anyone in need (Duffield, et al. 2001, 272). In Pakistan, aid was instead distributed based upon political favoritism to certain parties and jihadi groups, in an attempt at cooptation (International Crisis Group 2006, 5). In Kashmir, supporters of the opposition Pakistan People’s Parliamentarian Party and the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front were denied assistance, yet in NWFP, the welfare wings of the JUI and JI, two major partners to the MMA government were given provincial relief funds. Part of the favoritism shown towards these groups was due, in part, to the pervasiveness of JI political ideology in the Pakistani army (Kukereja and Singh, 2005, 16). The military’s response, in some cases, exacerbated divisions at the local and provincial level, particularly in regards to coordination between the two levels of government (International Crisis Group 2006, 4). Women, Afghan refugees and those who could not produce national identification cards, were often discriminated against and overlooked (International Crisis Group 2006, 6). 5 Foucaultian Power of the Body Power is defined as who possesses it, their aims, and is typically associated with governments or other bureaucratic entities (Hendrie 1997, 58). In the case of disaster relief, and in Pakistan particularly, it will be important to look at the administration of the disaster by the government and which organizations and ideologies the government allows to participate in that relief. Power, though, is not a commodity and to view it as such obfuscates “how things work at the level of on-going subjugation at the level of those continuous and uninterrupted processes which subject our bodies, govern our gestures, dictate our behaviors” (Foucault 1980, 97). Power is exercised, not possessed, and exists throughout society, not just practiced by the sovereign. Foucault argues that human society can be subjected to regulation and control through the application of “social technologies” that divide people into “subject-domains” which become subject to intervention and institutional practices (Hendrie 1997, 59). Similar to madness’ construction as a subject of scientific knowledge, disaster relief is constructed as a responsibility of governance, seen in the heavy hand that the Pakistani government played in relief efforts. For Foucault, the negative and positive aspects of power come together in government to form structures of coercion. In addition, the government possesses various forms of power, such as discipline, bio-power, and pastoral power (Bevir 1999, 345). Much of Foucault’s writings, particularly on control of populations, can be applied to the 2005 earthquake relief effort. Disaster relief, with its focus on victims, highlights how the “body is invested with relations of power and domination” (Foucault 1977, 26). The manner in which victims of disasters are treated, organized, and dealt with highlights these power relations, especially as AJK and the NWFP are predominately Pashtun, a minority in comparison to the predominate Urdu-speaking 6 population in the rest of Pakistan. This is an exercise of biopower. Throughout Discipline and Punish, Foucault refers to prisoners as patients; victims of disaster relief can be viewed similarly. Much like prisoners, rounded up into cells, victims are placed in refugee camps. In most disaster relief efforts, NGOs and other entities will help in setting up temporary camps to house those affected by the disaster. However, in Pakistan, NGOs and other humanitarian aid groups were excluded from relief efforts; the government carried out the major share of relief operations, allowing only Islamic charitable organizations to aid in the efforts. The Archipelago— Geography as an Influence on Power Power is based upon territory and controlling conduct, rather than, in the Machiavellian sense, controlling and identifying threats to power. The impact of the earthquake was felt most severely in the rural and remote areas of the NWFP. Based upon a study by the Fritz Institute, the extent of the damage in AJK is not known, as the Pakistani government strictly controlled access to the area and did not allow researchers to conduct surveys in the region due to political instability (Fritz Institute 2006, 4). This is an important concept to consider in light of the Pakistani government’s acceptance of assistance from jihadi groups, many of which have a stronger presence than the government in the earthquake-affected areas. By including these groups in the efforts, the government was able to monitor their activities. The arrangement also indicated the government’s awareness of its own tenuous position in the region.The earthquake brings up many important questions of geography, particularly in regards to the NWFP and AJK. These areas are distant from the government in Islamabad. The earthquake provided a situation in which these regions could be monitored and controlled; in a sense, this evokes what Foucault discussed as another notion of geography, the archipelago. Foucault saw the archipelago as a 7 punitive system that covers the entirety of society (Foucault 1980, 68). While Foucault was specifically referring to war management, the notion of the archipelago can also apply to disaster management. Management of the disaster has allowed for the government to monitor and administer regions that were previously out of its control. This is particularly important in the NWFP, where the region is comprised of predominately ethnic minorities, such as Pashtuns. In fact, before the earthquake, the manner in which the government administered this area was evocative of colonialism (International Crisis Group 2006, 1). Foucault, in “Body/Power” discusses the need for social body to be protected, in an almost medical sense; these measures included means of monitoring and surveillance (Foucault 1980: 55). In fact, the government controlled relief resources to such an extent that the victims became dependent. To this day, refugees are still dependent upon government assistance. (Frtiz Institute, 2006, 8). Perhaps because of the close proximity of Kashmir to India, the Pakistani government decided to take a leading role in disaster relief, and exclude humanitarian aid groups. There was also an absence of civilian oversight and inadequate governmental accountability (International Crisis Group 2006, 1). In some cases, the government justified its total control over relief efforts, citing the collapse of civilian authority in Kashmir and incapability to meet the task ahead of the them in the NWFP; in doing so, the government also failed to use expertise and assessment to meet local needs of the victims in AJK and the NWFP (International Crisis Group 2006, 4). Also, consultation with aid recipients was minimal, with no input in the decisionmaking processes related back to the humanitarian efforts (Fritz Institute 2006, 7). Overall, the government was reluctant to let other institutions aid in the efforts, though some, such as India, were far better equipped to aid in the relief efforts. Mutual mistrust and struggles for power in the region hampered opportunities to aid the victims of the disaster, as well as improve bilateral 8 relations. In fact, the military was more concerned with securing the Line of Control with India, than tending to civilian casualties. Pastoral Power- Jihadi Groups and the Relief Effort Many jihadi groups, by casting their relief efforts as “Islamic”, exercised pastoral power. Foucault identified pastoral power as requiring individuals to internalize various ideals and norms, driven by religious authorities (Bevir 1999, 351). In Foucault’s context, he was discussing the role of the Catholic Church in Europe; in this context, it is the rhetoric and actions of Islamic groups working in the relief efforts to gain greater legitimacy. For many of the Islamic organizations, it was important to limit the influence of Western NGOs. In an interview with the International Crisis Group, a representative of the Al-Rasheed Trust, a Deobandi organization associated with the JeM, stated “ ‘the need to offset the impact foreign NGOs are having on the minds of people…the relief activities are welcome, but[The Al-Rasheed Trust] cannot tolerate propagation of Western values and culture under the cover of relief work” (2006,13). The discourse of disaster relief also creates power effects in the social domain with serious negative effects. As Foucault observed, “certain knowledges of man are able to serve a technological function in the domination of people…not so much thanks to their capacity to establish a reign of ideological mystification, as their ability to define a certain field of empirical truth” (Foucault 1980, 237). Islamic rhetoric certainly cast INGOs in a negative light, creating a difficult operating situation for them. The Al-Rasheed Trust was particularly vocal in its criticism of Christian faith-based relief groups, arguing that the groups were proselytizing. In addition, the use of Islamic symbolism by many of the relief groups was evident, seen by the focus on building mosques and madrasas 9 throughout the affected areas. One of the first groups to enter into the stricken region was the Jammat-ud-Dawa, a spin-off of the militant LeT. Much of their relief efforts centered in the city of Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, where they spread out religious items such as prayer mats, as well as quilts (McGirk 2005, 2). The jihadi groups branded themselves as legitimate relief authority through the use of Islamic imagery and discourse. By accepting jihadi groups’ demands for a major disaster relief role, the Pakistani government bolstered the presence of these entities in AJK and the NWFP (International Crisis Group 2006, 1). Jihadi groups have also gained a degree of legitimacy from international aid organizations, such as United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees which distributed tents to the Al-Rasheed Trust, even though the UN has listed it as a terrorist organization (International Crisis Group 2006, 8). Most action that has been taken against jihadi groups has been superficial; the government is reluctant to address the issue of their presence fully, as many of these groups enjoy support in areas not controlled by the government. A more disturbing outcome of the jihadi groups aiding in the relief efforts, however, is that it has created a situation for these groups to recruit new members. Children orphaned by the earthquake were taken to madrasas operated by the jihadi groups (McGirk 2005, 2). Many of these groups compete for public support (International Crisis Group 2006, 12). This could potentially be a source of political and social conflict in the future. The amount of funding jihadi groups are able to obtain from donors throughout the Middle East is also a growing concern. As one representative from the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan stated, “the jihadi outfits have enough funds to sustain their relief efforts well into the later stages of reconstruction, while some other NGOs won’t have this capacity. So in the end, what are we left with? The [jihadi] NGOs of course” (International Crisis 10 Group 2006, 11). This will create a situation in which the people of AJK and the NWFP will come to rely on the jihadi groups for supplies, giving them biopower, that in the earlier stages of the relief efforts, had been conferred upon the government and military. Areas of Illegality- Undermining Power In the public execution, as described by Foucault, areas of illegality arose, such as onlookers attacking those carrying out the execution or other attempts to free the prisoner (Foucault 1977: 63). In much the same way, illegalities arose with the earthquake relief efforts. For example, the Pakistani government banned organizations like the Lashkhar-e-Toiba or the Jaishe-Mohammed to aid in the relief operations under new names or through front organizations. These organizations have largely operated in an area of illegality that has never been addressed by the Pakistani government. Often these groups are allowed to operate unmolested, despite claims from the government that action has been taken to curtail cross-border terrorism into India. In Discipline and Punish and in Power/Knowledge, Foucault identifies how the prison system serves to create more prisoners, or refine prisoners that are released. Likewise, allowing groups like the LeT to take a leading role in the disaster relief efforts has given the groups greater legitimacy in the region. This translates into greater support for their actions and makes it more difficult for the government to curb their activities or take the necessary actions against them to do so. According to Foucault, one of the reasons for moving executions within the walls of the prison was to avoid the growing illegalities around public execution and have greater control over the process and the prisoner. The Pakistani government has failed to address and block the activities of illegal groups in the relief efforts, creating, a situation of greater insecurity 11 and instability in the Kashmir region, which continues to be the major point of contention between India and Pakistan. Allowing populist jihadi groups to participate in relief efforts erodes the legitimacy of the Pakistani government. The LeT is far more visible in the actual relief efforts and are commended for their actions, while the government is criticized and seen as unable to take care of its citizens. Jihadi groups are permitted to operate in these areas because they are popular among the local population. Foucault would see this as the LeT exercising power in the stead of the government. due in part to their illegal existence, it was possible that Jihiadi groups’ actions were closely monitored by the Pakistani government. The jihadi groups modified their behavior because of this possible surveillance, thus engaging in a form of panopticonism, or self-regulating behavior because of the possibility of surveillance. With the conclusion of the initial stages of aid and relief, however, this self-monitoring behavior has ended. Since the earthquake, there has been a surge in terrorist activity in Jammu and Kashmir in India, mostly from militants associated with the LeT. Illegalities and public displays eventually caused punishment to become a private manner and an act between the state and the prisoner. In the same way, the Pakistani government should take more action against such groups and refuse them the opportunity for greater legitimacy by excluding them from relief operations. Efforts should have been made by the government to include NGOs and humanitarian groups that were willing simply to provide aid, without also pursuing proseltyzation. Conclusion Ten months after the earthquake, many victims are still left without basic assistance, and some with nothing at all. What assistance has been given, according to a study by the Fritz 12 Institute (2006), was predominately given by the Pakistani government and included food, shelter, livelihood needs, and medical services. The Fritz Institute found that the amount of aid given, though, was inadequate in comparison to the needs of the victims (p. 4). Individuals provided water and clothing and INGOs provided sanitation services. Over time, however, according to inhabitants interviewed, the role of the government declined, with INGOs taking an increasing role in the relief efforts (Fritz Institute 2006, 5). This is more than likely due to the government’s inability to sustain efforts for a prolonged period. But, as seen from Foucault’s theory, the government’s initial objective was met. The government was the first supplier of aid in the region, as it should be; however, it is the actions immediately after these initial steps that limited the space that other groups had to operate. INGOs and private individuals were cited as principal actors in relief efforts, but their visibility, in comparison to that of the military and government, was limited (Fritz Institute 2006, 6). Relief groups had to work so closely with the government that they operated largely under a military flag. Because of the weak position these groups had in relation to the government, civilian oversight and accountability they might have provided was absent. This adds another interpretation of the idea of control and power to Foucault’s theory. Control can be associative; relief efforts, because they were so closely monitored by the government, were assumed to have been conducted and provided by the government. The relief efforts in Pakistan also highlight, in a different manner, the impacts of geography on power, in a way Foucault could not possibly have imagined. Geography, whether it is because the region is remote or in close proximity to disputed land with India, played a major role in the = actions of the Pakistani government in the early stages of disaster relief. The military rushed to secure its geographic territory rather than aid the victims. The earthquake relief efforts could have provided an opportunity to build the capacity 13 of Pakistani and Kashmiri civil society, but because of the dependence groups had upon the military, this “window of opportunity was constrained” (International Crisis Group 2006, 7). The government, through surveillance and oversight and coordination, gained power over the relief efforts. Despite close control of the relief efforts, serious security and development issues have arisen that must be addressed for the stability of the region. Many of these have arisen due to the Pakistani government’s inability to control the work of the jihadi groups and the subsequent exercise of power by groups like the LeT have had in the region. Since the earthquake, the number of incidents of violence in Jammu and Kashmir, in India, has risen significantly. In addition, terrorist attacks deeper inside India, such as the Parliament attack in October of 2005 and the July 11th bombings in Mumbai in 2006, were carried out by the LeT, showing the growing strength of the groups that were involved in the earthquake relief efforts. In a sense, these groups, because of the greater influence and legitimacy they have gained from their relief efforts, are now exercising power, whether it is through administration in the affected areas, or carrying out operations in Kashmir and within India itself. Foucault’s concept of pastoral power can be seen in the actions and rhetoric of these groups; their exercise of power shows how pastoral power can be utilized as a sole legitimization for power. Not only have these groups “exercised power” in AJK and India, but the exercise of their power has even been taken against the Pakistani government. For example, a suicide attack was carried out recently against an army base in the Northwest Frontier Provinces. All indications show that it was the work of one of the jihadi groups in the region. The jihadi groups that have gained a foothold and legitimacy in AJK and NWFP are now seeking to solidify their claims to those regions and exercise power and control over the government of Pakistan itsel 14 Works Cited Bevir, Mark (1999). “Foucault, Power, and Institutions.” Political Studies, 47, 345-359. Duffield, Mark; Macrae, Joanna; & Curtis, Devon (2001). “Editorial: Politics and Humanitarian Aid.” Disasters, 25, 269-274. Duffield, Mark (2001). “Governing the Borderlands: Decoding the Power of Aid.” Disasters, 25, 308-320. Hendrie, Barbara (1997). “Knowledge and Power: A Critique of an International Relief Operation.” Disasters, 21, 57-76. Foucault, Michel (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books Foucault, Michel (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings. New York: Pantheon Books. Fritz Institute (2006). “Surviving the Pakistan Earthquake: Perceptions of the Affected One Year Later.” 1-12. International Crisis Group (2006). “Pakistan: Political Impact of the Earthquake.” Asia Briefing, 46, 1-16. International Crisis Group (2006). “Pakistan’s Tribal Areas: Appeasing the Militants.” Asia Report, 125, 1-35. Kukreja, Veena, and Singh, M.P., eds. (2005). Pakistan: Democracy, Development, and Security Issues. New Delhi: Sage Publications. McGirk, Jan (2005). “Kashmir: The Politics of an Earthquake.” Open Democracy. 1-3. United Nations System and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (2005). “Pakistan 2005 Earthquake: Early Recovery Framework.”