2. Sukrat B, Sirichotiyakul S. The prevalence and causes of anemia

HEMOGLOBIN STATUS OF PREGNANT WOMEN VISITING TERTIARY

CARE HOSPITALS OF PAKISTAN

Dileep Kumar Rohra 1 , Nazir Ahmad Solangi2, Zahida Memon 3 , Nusrat

H. Khan 4 , Syed Iqbal Azam 5

1 Department of Biological & Biomedical Sciences, Aga Khan University, Stadium

Road, Karachi, Pakistan

2 Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Nawabshah Medical College,

Nawabshah, Pakistan

3 Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Dow University of Health

Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan

4 Department of Gynecology & Obstetrics Unit III, Dow Medical College and Civil

Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan

5 Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, Stadium

Road, Karachi, Pakistan

Correspondence:

Dr Dileep K. Rohra

Associate Professor (Pharmacology), Department of Biological & Biomedical

Sciences, Aga Khan University, Stadium Road, P.O. Box 3500, Karachi 74800

Tel: +92-21-4864563

Fax:

E-mail:

+92-21-4934294, 4932095 dileep.rohra@aku.edu

1

ABSTRACT

Objective: To gather information about the haemoglobin levels in pregnant women who visited tertiary care hospitals of various cities in Pakistan for their antenatal care.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional and multi-centre study conducted at the

Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH), Karachi, Civil Hospital, Karachi (CHK) and Nawabshah Medical College Hospital (NMCH), Nawabshah. Copies of medicinal prescriptions given to pregnant patients attending the antenatal clinics were collected from January 1 to April 30, 2007. Reports or results of hemoglobin concentrations were also obtained from the patients.

Results: A total of 1709 pregnant women were recruited. Majority of the women

(67%) were from the age group of 25 to 34 years. 91% of the women had some degree of anemia. The number of women with moderate to severe anemia

(hemoglobin levels <8 or 8-9.9, respectively) was significantly higher in CHK and

NMCH compared to AKUH (p < 0.001). Whereas mild anemia (hemoglobin levels

10-10.9) or normal hemoglobin levels was significantly higher at AKUH (p <

0.001). Moderate anemia (hemoglobin levels of 8-9.9) was statistically more prevalent in second and third trimester, while mild anemia (hemoglobin levels of

10-10.9) was more prevalent in first trimester of pregnancy. The distribution of severe anemia however; was not different is the three trimesters. 90 to 92% of study subjects received the iron/vitamin/mineral supplements irrespective of the hemoglobin status of the woman.

2

Conclusion: Prevalence and severity of anemia in pregnant subjects attending the tertiary care hospitals of Pakistan is exceptionally high. Current findings highlight the anemia in pregnancy as a priority area of concern.

Key words: Anemia, Haemoglobin, Pregnancy

3

INTRODUCTION

Anaemia is defined as the condition in which there is either less than the normal number of red blood cells or less than the normal quantity of hemoglobin in the blood.

1 In majority of cases, the anemia is due to decreased amount of nutrient(s) needed for haemoglobin synthesis. Numerous studies from the developing countries have shown that anemia especially the iron deficiency is highly prevalent in the pregnant women.

2-5 In Pakistan, however, there are no statistics regarding the burden of this disease. In pregnant women however, it is supposed to be more common due to obvious reasons. In this population, the anaemia may become the underlying cause of maternal mortality and perinatal mortality as well complications to the fetus including increased risk of premature delivery and low birth weights.

6 Lone FW et al (2004) have also reported the adverse fetal outcomes as well as perinatal complications associated with maternal anemia in

Pakistan.

7

The current study was designed with the objective of determining the haemoglobin levels in pregnant women who visited tertiary care hospitals of various cities in Pakistan for their antenatal care.

4

METHODS

Place and duration: This was a descriptive cross-sectional multi-centre study encompassing three tertiary care hospitals i.e Aga Khan university Hospital

(AKUH), Karachi, Civil Hospital, Karachi (CHK) and Nawabshah Medical

College Hospital (NMCH), Nawabshah. Ethical clearance was obtained from the

Ethical Review Committee of the Aga Khan University, Karachi. In addition to that a written clearance was obtained from the Heads of the sampling units for obtaining the data from their respective Hospitals. Copies of medicinal prescriptions given to pregnant patients attending the antenatal clinics of CHK and NMCH were collected from January 1 to April 30, 2007. Reports or results of hemoglobin concentrations were also obtained from the patients. Since the

AKUH maintains a record of all the patients attending the clinics, data was collected from the medical records of the pregnant women attending the antenatal clinics during the above-mentioned period.

Inclusion criteria: Only those subjects were included in the study who attended the obstetrical clinics of the AKUH, CHK and NMCH for routine antenatal check up without having other ailment and whose blood hemoglobin levels were known at the time of encounter.

Definitions of anemia: Anemia was labeled when the pregnant women had a haemoglobin level of < 11 g/dl in accordance with the definition of World Health

Organisation.

1 Anemia was further categorized as Mild, Moderate and Severe according to the following criteria:

5

Mild: When hemoglobin levels were in the range of 10 to 10.9 gm/dl.

Moderate: When hemoglobin levels were in the range of 8 to 9.9 gm/dl.

Severe: When hemoglobin levels were < 8 gm/dl.

Data was recorded on a structured questionnaire that contained information on the demography of patients and the drugs prescribed to them.

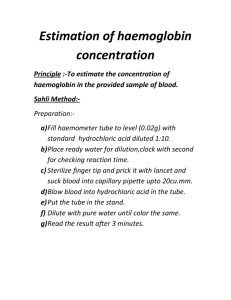

Statistical analysis: Data of 1709 pregnant women were collected from three tertiary care hospitals. The collected data was entered and analyzed using SPSS version 15.0. 2 test was used to compare the association of haemoglobin level with sampling units (hospitals) and different trimesters.

6

RESULTS

Prevalence and severity of anemia: A total of 8654 pregnant women were contacted in the ante-natal clinics of the AKUH, CHK and CMCH. Out of which, we were able to recruit 1709 women (19.7%) based on the criteria as explained in the METHODS section. Majority of the women (67%) were from the age group of

25 to 34 years. Hemoglobin levels during pregnancy in each sampling sample are analyzed in Table 1. Approximately 91% of the pregnant women had some degree of anemia (Table 1). A significant association between hemoglobin levels during pregnancy and sampling units was observed (p < 0.001). It was noted that the number of women with moderate to severe anemia (hemoglobin levels of 8-9.9 and <8, respectively) was significantly higher in CHK and NMCH compared to

AKUH (Table 1). Whereas mild anemia (hemoglobin levels 10-10.9) or normal hemoglobin levels was significantly higher at AKUH (p < 0.001).

Association of anemia with the trimester of pregnancy: We also determined the association between anemia and trimester of pregnancy. Before making an analysis, we ensured that there is parity in the sample size from each trimester and sampling unit. The break up of sample size from each trimester and sampling unit is depicted in Table 2. Interestingly, a significant association was observed between haemoglobin level and trimester of pregnancy (p < 0.001).

Moderate anemia (hemoglobin levels between 8 to 9.9) was more prevalent in second and third trimester, while mild anemia (hemoglobin level between 10 and

10.9) was more prevalent in first trimester of pregnancy (Table 3). The distribution of severe anemia however; was not different is the three trimesters.

7

Prescribing trends of iron and vitamin supplements: Prescribing behaviour of health care providers to pregnant women was also evaluated (Table 4). As presented in Table, 90 to 92% of study subjects received the iron/vitamin/mineral supplements (frequently a combination of all) irrespective of the hemoglobin status of the woman. There was no statistical difference between the anemic and non-anemic groups as far as the iron/vitamin/mineral supplements prescribed to them was concerned.

8

DISCUSSION

Anemia during pregnancy, particularly iron deficiency anemia, continues to be a world-wide concern. The present study demonstrates higher prevalence of anemia in pregnancy in women attending ante-natal clinics at the tertiary care hospitals of Pakistan. Overall, a prevalence of 91% was found. If we closely look at the state of affairs of pregnant women attending the public sector hospitals;

CHK and NMCH (leaving aside the data obtained form the AKUH), it was shocking to note that 98% of the women had some degree of anemia. More than

56% of those women had moderate to severe anemia. The prevalence of anemia was lowest in patients attending the AKUH (78%) and out of those 78%, 82% had mild anemia. UNO has reported that 56% of pregnant women in low income countries are suffering from anemia, in contrast to 18% in high-income countries.

8 Researchers from various developing countries have shown a prevalence of anemia in pregnancy from 19 to 50%.

9-11 Compared to these reports, the figures of hemoglobin levels in our study are really disturbing. Here we strongly recommend further nation-wide studies with more controlled conditions to measure the burden of anemia in pregnancy along with its associated maternal and fetal complications. Based on the those studies, it might be possible to reassess the definition of anemia in the context of local conditions keeping in mind the dietary, racial and other differences since it is highly unlikely that almost all the women have anemia during pregnancy. Indeed,

Micozzi (1978) raised the similar concerns that cut-off values for anemia obtained on Western population do not hold true for Asian populations.

12

9

Nevertheless, the findings of the present study should pave the way for further similar studies.

Although determining the causes and association of anemia was not the objective of this study, it can easily be assumed that as reported from various parts of the world, iron deficiency anemia is highly prevalent among the pregnant population.

9,13,14 We speculate that adverse haemoglobin status of pregnant women attending public sector hospital might be due to the socioeconomic status as well as level of education. Conceivably, due to high cost of health care at the

AKUH; a private sector tertiary care hospital, public health sector hospitals are the only option for people from lower income for seeking medical advice and treatment. Generally speaking, less income in Pakistan is also associated with poor educational status and high parity. Brunvand et al (1995) have shown an interesting positive correlation between the dietary habits of Pakistani population and the prevalence of anemia. They have concluded that the use of chapatti is associated with the decreased absorption of iron and eventually the iron-deficiency anemia 15 . All these factors together might be contributing towards high prevalence of anemia in women attending tertiary care hospitals especially public care hospitals.

Another finding of this study was the progressive deteriorating haemoglobin status with the progression of pregnancy. While mild anemia was more prevalent in first trimester, significantly greater number of pregnant women was found to be having moderate anemia in second and third trimester. This is probably due

10

to increasing requirements of the iron as the pregnancy progresses coupled with the fact that iron stores are exhausted in most women in the second and third trimester.

16

However, it was interesting to note that severe anemia was not associated with the gestational age. Almost similar proportion of women (5-7%) with severe anemia was observed in all the trimesters. The plausible explanation of this finding is that the severe anemia observed was not entirely related to the current pregnancy. It is likely that some other disorder causing anemia has been complicated by the current pregnancy leading to severe anemia

Routine iron prophylaxis is commonly recommended for pregnant women.

Arguments used in support of this practice have included decreasing haemoglobin values that are improved by iron and calculations of the extra iron needed for the growth of the fetus and placenta. We also tried to determine the iron and vitamin/mineral prescribing behaviour of physicians in Pakistan. It was noted with concern that physicians prescribe the iron and vitamin supplements to pregnant women habitually as a matter of routine not on the need basis. As evident from Table 4, 92% of the anemic and 90% of the normal women were prescribed supplements. The casual attitude of the health care providers is manifested from the fact that 8% of the women who were in dire need of work up on hemoglobin level were not prescribed any iron supplement. On the contrary,

90% of the women, whose haemoglobin levels were normal, did receive at least one iron and/or vitamin supplement. Recently, it has been shown that routine

11

iron supplementation to non-anemic pregnant women is associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

17 From these observations, it is recommended that the prescription of iron and vitamin supplements should be dictated by the needs of the patient.

The limitations of the study were that hemoglobin levels were not determined by the investigators themselves, but they relied on the reports issue by local clinical laboratories. Nonetheless, this does not blunt the validity of the study since retrospective studies for which data has been obtained from the medical records from different data bases are there in the medical literature.

18

12

CONCLUSION

Prevalence and severity of anemia in pregnant subjects attending the tertiary care hospitals of Pakistan is exceptionally high. Current findings call authorities to consider anemia in pregnancy as a priority area of concern. Measures need to be devised on urgent basis to prevent and treat anemia during pregnancy in order to prevent fetal and maternal complications associated with it.

13

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Higher Education Commission, Islamabad, Pakistan vide Grant No. 20-480/R&D/06/764.

14

REFERENCES

1.

Beutler E, Waalen J. The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood 2006; 107:1747–

1750.

2.

Sukrat B, Sirichotiyakul S. The prevalence and causes of anemia during pregnancy in Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai

2006; 89 Suppl 4:S142-146.

3.

Suega K, Dharmayuda TG, Sutarga IM, Bakta IM. Iron-deficiency anemia in pregnant women in Bali, Indonesia: a profile of risk factors and epidemiology. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2002; 33:604-

607.

4.

Desalegn S. Prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy in Jima town, southwestern Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 1993; 31:251-258.

5.

Toteja GS, Singh P, Dhillon BS, Saxena BN, Ahmed FU, Singh RP, et al.

Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women and adolescent girls in 16 districts of India. Food Nutr Bull 2006; 27:311-315.

6.

Chang S-C, O’Brien KO, Nathanson MS, Mancini J, Witter FR.

Hemoglobin concentrations influence birth outcomes in pregnant African-

American adolescents. J Nutr 2003; 133:2348–2355.

7.

Lone FW, Qureshi RN, Emmanuel F. Maternal anaemia and its impact on perinatal outcome in a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. East Mediterr

Health J 2004; 10:801-807.

8.

United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination, Subcommittee on Nutrition (ACC/SCN). Fourth Report on the World Nutrition

15

Situation: Nutrition throughout the Life Cycle. Geneva: ACC/SCN in collaboration with International Food Policy Research Institute, 2000.

9.

Hyder SMZ, Persson L-A, Chowdhury M, Lo¨nnerdal B, Ekstro E-C.

Anaemia and iron deficiency during pregnancy in rural Bangladesh.

Public Health Nutrition 2004; 7:1065–1070.

10.

Chotnopparatpattara P, Limpongsanurak S, Charnngam P. The prevalence and risk factors of anemia in pregnant women. J Med Assoc

Thai 2003: 86:1001-1007.

11.

Martí-Carvajal A, Peña-Martí G, Comunian G, Muñoz S. Prevalence of anemia during pregnancy: results of Valencia (Venezuela) anemia during pregnancy study. Arch Latinoam Nutr 2002; 52:5-11.

12.

Micozzi M. On definition of anemia in pregnancy. A J P H 1978; 68:907-

908.

13.

Meier PR, Nickerson HJ, Olson KA, Berg RL, Meyer JA. Prevention of iron deficiency anemia in adolescent and adult pregnancies. Clin Med Res

1:29-36.

14.

Abel R, Rajaratnam J, Kalaimani A, Kirubakaran S. Can iron status be improved in each of the three trimesters? A community-based study. Eur J

Clin Nutr 2000; 54:490-493.

16

15.

Brunvand L, Henriksen C, Larsson M, Sandberg AS. Iron deficiency among pregnant Pakistanis in Norway and the content of phytic acid in their diet. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1995; 74:520-525.

16.

Barrett JF, Whittaker PG, Williams JG, Lind T. Absorption of non-haem iron from food during normal pregnancy. Br Med J 1994; 309:79-82.

17.

Ziaei S, Norrozi M, Faghihzadeh S, Jafarbegloo E. A randomised placebocontrolled trial to determine the effect of iron supplementation on pregnancy outcome in pregnant women with haemoglobin > or = 13.2 g/dl.

B J O G 2007; 114:684-688.

18.

Massot C, Vanderpas J. A survey of iron deficiency anaemia during pregnancy in Belgium: analysis of routine hospital laboratory data in

Mons. Acta Clin Belg 2003; 58:169-177.

17