Shewas and Hateph-Vowels - The CrossWire Bible Society

advertisement

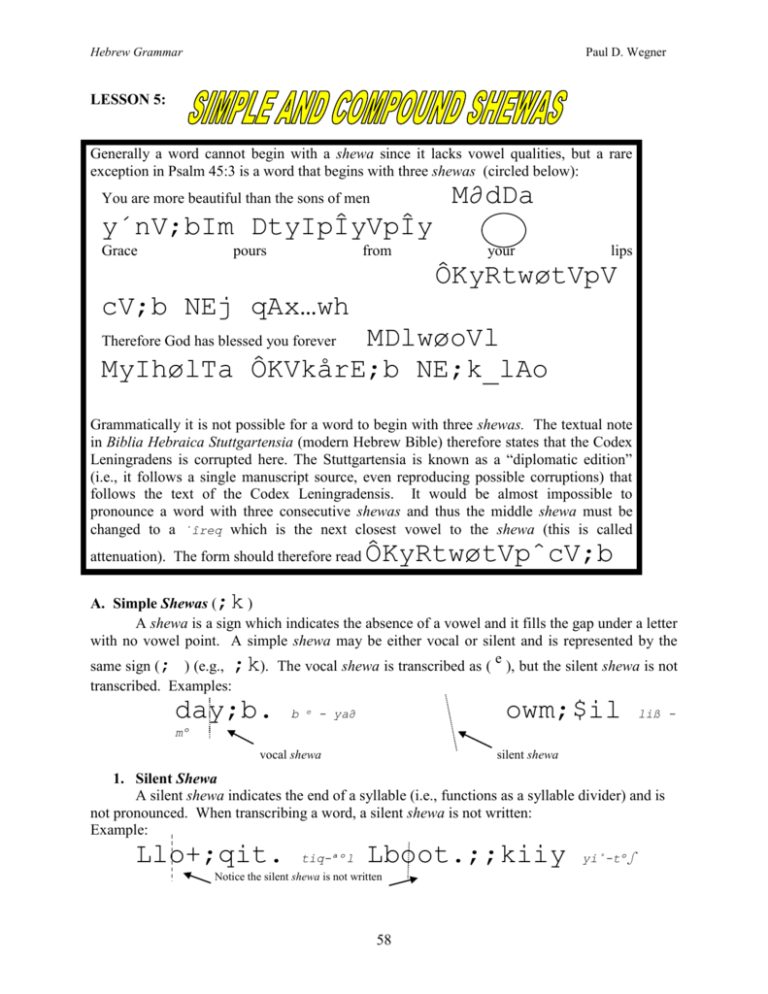

Hebrew Grammar Paul D. Wegner LESSON 5: Generally a word cannot begin with a shewa since it lacks vowel qualities, but a rare exception in Psalm 45:3 is a word that begins with three shewas (circled below): M∂dDa You are more beautiful than the sons of men y´nV;bIm DtyIpÎyVpÎy Grace pours from your lips ÔKyRtwøtVpV cV;b NEj qAx…wh MDlwøoVl MyIhølTa ÔKVkårE;b NE;k_lAo Therefore God has blessed you forever Grammatically it is not possible for a word to begin with three shewas. The textual note in Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (modern Hebrew Bible) therefore states that the Codex Leningradens is corrupted here. The Stuttgartensia is known as a “diplomatic edition” (i.e., it follows a single manuscript source, even reproducing possible corruptions) that follows the text of the Codex Leningradensis. It would be almost impossible to pronounce a word with three consecutive shewas and thus the middle shewa must be changed to a ˙îreq which is the next closest vowel to the shewa (this is called attenuation). The form should therefore read ÔKyRtwøtVpˆcV;b A. Simple Shewas (;k ) A shewa is a sign which indicates the absence of a vowel and it fills the gap under a letter with no vowel point. A simple shewa may be either vocal or silent and is represented by the e same sign (; ) (e.g., ;k). The vocal shewa is transcribed as ( ), but the silent shewa is not transcribed. Examples: day;b. b e owm;$il - ya∂ liß - mº vocal shewa silent shewa 1. Silent Shewa A silent shewa indicates the end of a syllable (i.e., functions as a syllable divider) and is not pronounced. When transcribing a word, a silent shewa is not written: Example: Llo+;qit. tiq-ªºl Lboot.;;kiiy Notice the silent shewa is not written 58 yi˚-tº∫ Hebrew Grammar Paul D. Wegner There are two principles that help to determine whether the shewa is silent: a. Following a short, unaccented vowel. In Hebrew there cannot be a short vowel in a distant open syllable—the syllable must close thereby causing a closed unaccented syllable. Examples : hfmfh;lim Mek;mi) silent shewa Note that the final consonant of a word does not regularly contain a silent shewa even though it does close a syllable. However, there are two notable exceptions: 1. When a word ends with two unvocalized consonants (e.g., common in the Perfect 2FS form, ;;;t.;batfk. kœ-tabt ). In this case, the syllable is said to doubly close and both unvocalized consonants take a silent shewa. 2. A kœπ (K ) without a vowel carries a silent shewa to distinguish it from the final nûn (N ). Example: Kele≥em me-lek b. The first shewa in a series of two. Examples: w.r;m;$iy w.b;t.;kit. silent shewa w.k;l;miy vocal shewa silent shewa (closes the syllable) 2. Vocal Shewa e A vocal shewa always indicates the beginning of a syllable and is transliterated as ( ). e Example: =b A shewa is vocal if it appears: a. At the beginning of the word. ;b. Example: rowk;b. b e - ˚ôr b. The second one in a series of two shewas. Example: w.r;m;$iy vocal shewa yiß-m e- rû silent shewa c. Following a Dagesh Forte (this is a doubling dot that is discussed later). Example: w.r;b.id. dib-be-rû 59 Hebrew Grammar Paul D. Wegner d. Following a long vowel. Example: w.k;l"y y®-l e-kû w.b ;t. ;kiy = yi˚-te-∫û vocal shewa silent shewa An important rule concerning two consecutive shewas is called The Rule of Shewa: The Rule of Shewa: A WORD CANNOT BEGIN WITH TWO CONSONANTS THAT DO NOT HAVE VOWELS (i.e., TWO VOCAL SHEWAS). THE FIRST VOCAL SHEWA THEREFORE BECOMES THE NEAREST, SHORT VOWEL (i.e., ˙îreq ). Example: l)w.m:$ + ;l = l)w.m:$il :AA: :A:AE: F: B. Compound (Composite) Shewas: (e.g., , , ) Technically the compound shewa is a short vowel plus a simple vocal shewa, sometimes referred to as ˙œªeπ (half) vowels. Example: a + : MowdE:)el = A:x as in MowlA:x MyimfkA:x “dream” boqA:(£ay Compound shewas are only placed under guttural letters (), h, x, () and r r®ß, because these letters need a helping sound. A compound shewa is not a vowel, however; it is merely a place holder. In pronunciation, a compound shewa is to be slightly colored by the corresponding short vowel. There are three composite shewas, one for each of the semitic vowel classes (i.e., A, I, and U). A:)) (E:)) (F:)) A-Class compound shewa is a ˙œªeπ (half) patha˙ ( I-Class compound shewa is a ˙œªeπ (half) se©ºl U-Class compound shewa is a ˙œªeπ (half) qœm®∆ (The qœm®∆ of the ˙œªeπ qœm®∆ is always a short “o”.) 60 Hebrew Grammar Paul D. Wegner When a simple vocal shewa immediately precedes a compound shewa (remember the Rule of Shewa—a word cannot begin with two vocal shewas), the simple vocal shewa changes to the corresponding full short vowel of the ˙œªeπ vocalization. Examples: MowlA:A:x + ;b. = MowlA:xab. MowdEE:) + ;;l = MowlA:xaal Summary: 1. There are two types of simple shewas: a. Silent Shewa: indicates the end of a syllable and is silent. b. Vocal Shewa: indicates the beginning of a syllable and is vocal. 2. Rules for determining shewas: a. Silent Shewa: Whenever the shewa closes the syllable it is silent (e.g. bot.;kiy ). Silent Shewa b. Vocal Shewa: Whenever a shewa is the only vowel in a syllable it must be vocal (e.g. rowk;b. ) Vocal Shewa c. Rule of Shewa: A word cannot begin with two vowelless consonants and thus the first vocal shewa must go to the nearest, short vowel (e.g., l)w.m:$ + ;l = l)w.m:$il 3. Compound Shewas: These shewas go under Gutturals and r®ß in order to provide a helping vowel sound. 61 Hebrew Grammar Paul D. Wegner Exercise 5 A. Divide the following words into syllables and label the shewas (i.e., vocal = v; and silent = s): Examples: MyihlE:) Myih l E:) vocal shewa w.l;lah w.l ;lah silent shewa 1. lo+:qit. _______ 5. hfn;b≥ot.;kit. _______ 2. Mek.;mi) _______ 6. w.b;t.;kiy _______ 3. hfmfx;lim _______ 7. rowk;b. 8. Met.;rak;zw. _______ 4. w.r;m;$iy _______ _______ B. Write the names of the ˙œªeπ vowels in the following words: 1. MowlA:x __________________ 4. henA:xam __________________ 2. MyihlE:) __________________ 5. K;bfzEE:(e) __________________ 3. yirA:) __________________ __________________ 62 6. damF:(£fh Hebrew Grammar Paul D. Wegner For Further Reading: Gesenius, W. and E. Kautzsch. Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar. Trans. A. E. Cowley. Oxford: Clarendon, 1910. Pp. 51–54. Kelley, P. H. Biblcal Hebrew: An Introductory Grammar. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992. Pp. 8, 13. Lambdin, T. O. Introduction to Biblical Hebrew. New York: Scribner, 1971. Pp. xix–xx. Seow, C. L. A Grammar for Biblical Hebrew. Nashville: Abingdon, 1989. Pp. 10-11. Weingreen, J. A Practical Grammar for Classical Hebrew. 2nd Ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1959. Pp. 8–14. 63