What precisely is an essay? The most useful definition is that in

advertisement

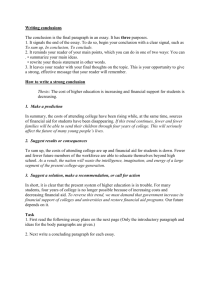

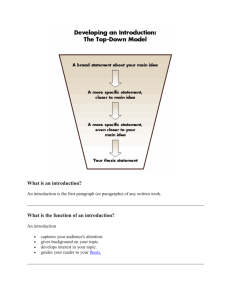

What precisely is an essay? The most useful definition is that in Webster's New International Dictionary: "A short literary composition dealing with a single subject, usually from a personal point of view, and permitting a considerable freedom of style and method". There are several methods, or rather patterns that you may use in writing your essay. But before making up your mind about the methods it seems reasonable that you make a rough plan of your essay and divide it into Introduction, Development, and Conclusion. 1. Introduction The subject of your essay should be presented to the reader in the way that you think is most likely to make him want to read to the end. The main purpose of Introduction is to present a thesis statement, a sentence explaining the controlling idea of the essay. The thesis statement will usually be the last sentence in the introductory paragraph. 2. Development or Body paragraphs supporting the thesis statement. Each paragraph should be complete and unified, with its own topic sentence that supports the thesis statement in the introduction. One effective way to support your thesis statement is to give examples that either illustrate or prove your main points. To be effective, the examples you choose must be specific (creating pictures in the minds of your readers), appropriate (directly relating to the controlling idea) and representative (describing a typical experience to prove the point). Make sure you keep body paragraphs distinct: each one has its own main idea and does not repeat information from other body paragraphs. 3. Conclusion - the last paragraph that summarises the controlling idea of your thesis statement. This can be short, but it should be more than one sentence. Conclusions leave the reader with some final thoughts (but not new ideas) on the main idea and the supporting points. Like introductions, conclusions are typically more general than body paragraphs because they move away from the specific topic and shift toward the reader's or the writer's life. The flow in a typical essay is from general (introduction) to specific (the body) and back to general (the conclusion). The fundamental qualities of effective prose are unity, coherence, emphasis and variety. Unity and coherence in sentences help to make ideas logical and clear, emphasis makes them forceful, variety lends interest. Guidelines on Unity 1. Write unified logical sentences. Bring into a sentence only related thoughts, use two or more sentences for thoughts that are not closely related. Make sure that the ideas in each sentence are related and that the relationship is immediately clear to the reader. Unrelated: Yesterday Ted sprained his ankle, and he could not find his chemistry notes anywhere. Related: Accident-prone all day yesterday, Ted not only sprained his ankle but also lost his chemistry notes. 2. Do not allow excessive detail to obscure the central thought of the sentence. Bring into a sentence only pertinent details. Omit tedious details and irrelevant side remarks. Parallel structure, rhythm, careful punctuation and well-placed connectives can bind a sentence into a perfect unit. Guidelines on emphasis. Select words and arrange the parts of the sentence, as well as sentences in paragraphs, to give emphasis to important ideas. Since ideas vary in importance expression of them should vary in emphasis. In most types of writing, word order may be changed to achieve emphasis without losing naturalness of expression. 1. Gain emphasis by placing important words at the beginning or end of the sentence especially at the end. 2. Since semicolons, sometimes called weak periods, are strong punctuation marks, words placed before and after a semicolon have an important position. 3. Gain emphasis by using the active voice instead of passive voice. Unemphatic Little attention is being paid to cheap, nutritious foods by the average shopper. Emphatic The average shopper is paying little attention to cheap, nutritious foods. 4. Gain emphasis by abruptly changing sentence length. The short sentence, which abruptly follows a much longer one, is emphatic. 5. A question in your narration will also call the attention of your reader. Guidelines on variety 1. Vary the structure and the length of your sentences to make your whole composition pleasing and effective. 2. Avoid a long series of sentences beginning with the subject. Vary the beginning. - an adverb or an adverb clause - a prepositional phrase or a participial phrase - a conjunction such as and, but, or, nor, for, or yet. Guidelines on Coherence 1. Give unity to the paragraph by making each sentence contribute to the central thought. Do not make rambling statements that are only vaguely related to your topic. As you write a paragraph, every statement should pertain to its main idea. 2. Give coherence to the paragraph by so interlinking the sentences that the thought flows smoothly from one sentence to the next. Provide transitions between paragraphs as well as between sentences. Link sentences by using such transitional expressions as the following: Addition: moreover, further, furthermore, besides, and, and then, likewise, also, nor, again, in addition, equally important, next, in the first place, in the second place, finally, Comparison: similarly, likewise, in like manner Contrast: but, yet, and yet, however, still, nevertheless, on the other hand, on the contrary, even so, notwithstanding, for all that, in contrast to this, at the same time, although this may be true, otherwise Place: here, beyond, nearby, opposite to, adjacent to, on the opposite side Purpose: to this end, for this purpose, with this object Result: hence, therefore, accordingly, consequently, thus, thereupon, as a result, then Summary, repetition, exemplification, intensification: to sum up, in brief, on the whole, in sum, in short, in other words, that is, to be sure, as has been noted, for example, for instance, in fact, indeed, to tell the truth, in any event. Time: meanwhile, at length, soon, after a few days, in the meantime, afterward, later. 3. Arrange the sentences of the paragraph in a clear, logical order. There are several common, logical ways to order the sentences in a paragraph. The choice of an appropriate order depends on the context and on the writer's purpose. Perhaps the simplest and most common order is time order. Other types of paragraphs often have a time element that makes a chronological arrangement both possible and natural. For example, in explaining a process - how something is done or made - the writer can follow the process through, step by step. Passages that have no evident time order can sometimes be arranged in space order, in which the paragraph moves from east to west, from near to distant, from left to right, and so on. This order is used especially in descriptive writing. Another good arrangement of sentences is in the order of climax. Here the least important idea is stated first, and the others are given in order of increasing importance. Sometimes the movement within the paragraph may be from the general to the particular, from the particular to the general, or from the familiar to the unfamiliar. A paragraph may begin with a general statement or idea, which is then supported by particular details. Reversing the process, it may begin with 4. To make your writing coherent, you should avoid needless shifts in grammatical structures, in tone or style, and in viewpoint. Abrupt, unnecessary shifts -for example, from past to present, from singular to plural, from formal diction to slang, from one perspective to another - tend to obscure a writer's meaning and thus to cause needless difficulty in reading. To make your writing easy to read and to understand you should first of all be logical in the way you present your ideas. You should use only the reasonable proof to support your arguments. There are several common errors in reasoning (fallacies) that people make when they present arguments. By being aware of these fallacies and checking your arguments carefully, you should be able to avoid making errors that will cause your readers to distrust your arguments. KINDS OF LOGICAL FALLACIES 1. False Cause Fallacy The post hoc fallacy occurs when people assume that just because one event follows another, the first event was the cause of the second. For example, suppose you observe a young child entering the yard belonging to people who have a big dog. You cannot see the child once the gate closes. Soon after the child enters the yard you hear him crying. If you assume, without seeing what happened, that the child is crying because the dog bit him or frightened him, you make an error in thinking called the false cause fallacy. It is very possible that the child tipped entering the yard or that another child frightened or hurt him. The conclusion was reached using wrong evidence. 2. Hasty generalisation Coming to quick conclusion without having adequate evidence is a frequent and hazardous error in reasoning. This kind of thinking error leads to prejudice and can destroy human relations. People often make hasty generalisations when they find themselves in cultures different from their own. People tend to assume that what they experience in a new situation is the common experience in that situation. What they experience, however, may be the exception to the rule. 3. False analogy An analogy is a comparison made to make the point clearer. Analogies compare two things that are basically unlike each other, but that have some important characteristics in common. A fallacy takes place, however, when a person compares two things that are similar only in unimportant ways, and concludes that because of these similarities, the two things are alike in other ways. 4. Circular argument People also reach unsupported conclusions when they use circular reasoning. A person using circular reasoning repeats the same thing in different words rather than giving effective proof for a conclusion. Instead of giving evidence to prove a point, the person using this kind of faulty reasoning merely repeats the point. The following statement is the example of circular reasoning. The death penalty for drug pushers is the answer to the drug problem in the United States; therefore, every state should enforce a death penalty for those convicted of selling drugs and there will be no more drug problem in the country. Notice that there is no proof given that the death penalty is actually a deterrent to those who sell drugs. The statement merely says it is. No thinking person will be convinced by this argument. If the point that the writer is trying to make is a valid one, the evidence that proves this point must be carefully outlined for the reader. Only then will a thoughtful reader be convinced by the argument. 5. Misuse of Authority It is easy to be mislead by "authorities" who are really not authorities at all. Incompetent authorities include celebrities selling products about which they have no more knowledge than the average person. It is also a misuse of authority to quote a person who does know a great deal about a subject, but who is extremely biased. Quoting biased "authorities" will make your evidence biased and, therefore, unconvincing to your audience. 6. Card stacking Card stacking occurs when writers use only data that support their arguments and fail to use that which is contrary to their points of view. Although the facts that the writers employ may be both pertinent and correct, if they present only one side of the picture, they do not form a good argument. They deceive the reader. As you prepare to write an essay of persuasion, you will want to make a list of all the arguments against the position you are taking, as well as all the arguments for your point of view. If you were to use only those arguments on the "for" side, you would be "stacking the cards" in your favour. As your reader thinks of the unmentioned reasons why your point of view may have disadvantages, you will begin to lose your argument for the reader. It is much more effective to include a discussion of the main arguments against your point of view, then show how these arguments are not as important as those that support your position. 7. Either/or (black/white) fallacy When thinking about complex issues, some people fall into a pattern of thought that assigns only two sides to every issue - good and bad, or right and wrong. Complex issues cannot be simplified in this way. A writer who oversimplifies complex issues is not respected by readers. This error in thinking, called the either-or fallacy, causes people to assume that there are only two sides to as issue; that it must be either this way or that way, with no alternatives. There are very few so-called black and white situations or issues. 8. Stereotypes Stereotypes are formed when people use knowledge about one or two members of a particular race, country, or religion to generalise about the entire group. Stereotypes about people in the United States. People from the United States are: outgoing, friendly, informal hard working disrespectful of authority racially prejudiced not knowledgeable about other countries always in a hurry. These words and phrases are stereotypes of a nation of people. This nation, like all other nations, is made up of many different kinds of people; therefore, while the words and phrases may apply to some people from this country, they certainly do not apply to all people from the United States. It is not logical to make a general statement about anything based on just one or two examples; therefore, to form general ideas about groups of people based on one or two examples is illogical reasoning. To revise your essay you may find it useful to answer the following questions: Is the content of your essay appropriate to the title and the introduction? Does it have a clear thesis statement Is there a clear presentation and development of ideas? Is all information relevant? Check for any information that may be interesting but is irrelevant to the topic, redundant or repetitive. Do you give reasons for the points you introduce? Will the reader be able to follow your line of reasoning? Do all sentences / paragraphs have a logical connection with preceding / following sentences/paragraphs? Did you manage to avoid logical fallacies in developing the subject of your essay? Have you selected an appropriate level of formality (e.g. no use of contractions such as it's instead of it is)? Is your language too complex or too simplistic? Have you kept to the objective structures that characterise academic writing, such as impersonal forms and passive verbs? Did you manage to avoid referring to your authorship? Did you use English grammar effectively to convey the message (subject-verb agreement, word order, the use of countable/uncountable nouns, etc.)? Did you follow the rules for spelling, capitalisation, and punctuation?