Parish Church History: Construction, Bells, and Inscriptions

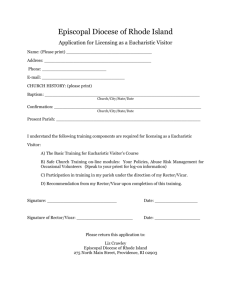

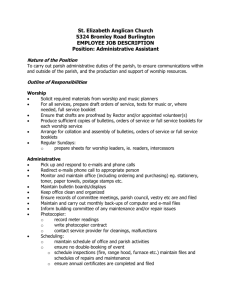

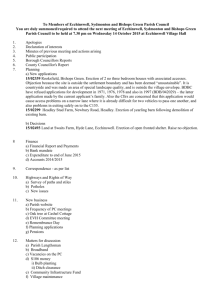

advertisement