Donna Santa Marie

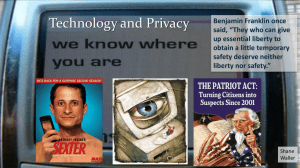

advertisement