GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON (1788-1824)

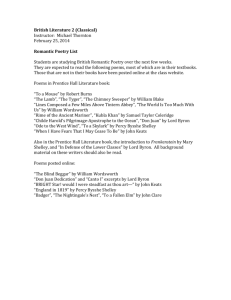

advertisement

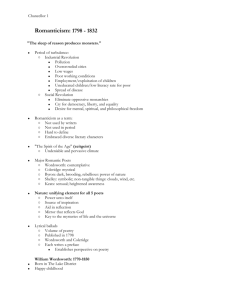

GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON (1788-1824) PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY (1792-1822) JOHN KEATS (1795-1822) History of English Literature in the 1850s by the French critic: only a few pages on Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley and Keats but a long chapter on Lord Byron, ”the greatest and most English of these artists; he is so great and so English that from him alone we shall learn more truths of his country and of his age than from all the rest together.” Immense European reputation (Goethe, Balzac, Stendhal, Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Melville, Delacroix, Beethoven, Berlioz) but (after his early appeal) acknowledged by very few in England (most notably by Shelley) George Gordon Byron (1788-1824) descended from colourful, violent and dissolute aristocratic families, brought up in near poverty in Aberdeen; at the age of ten becomes 6th Lord Byron most seductively attractive („so beautiful a countenance,” Coleridge wrote „I scarcely ever saw … his eyes the open portals of the sun—things of light, and for light”) but born with a deformed right foot, was lame all through his life („As to your immortality, if people are to live, why die? And our carcasses, which are to rise again, are they worth raising? I hope if mine is, I shall have a better pair of legs than I have moved on these two-and-twenty years, or I shall be sadly behind in the squeeze into Paradise.”) Trinity College, Cambridge (1805-1808) extravagant life, depts, I. 1807-1812 Hours of Idleness (1807) conventional verses, pastime activity of a young aristocrat(„It is highly improbable, from my situation and pursuits hereafter, that I should ever obtrude myself a second time on the public; nor even, in the very doubtful event of present indulgence, shall I be tempted to commit a future trespass of the same nature.”) received very harsh criticism from The Edinburgh Review („so much stagnant water”), which provoked the writing of his first important poem: English Bards and Scotch Reviewers (1809) : uncompromising satire on contemporary literary life in the couplet style of Pope; tactlessly ridiculing the famous contemporaries (incl. Scott, Wordsworth and Coleridge) Next comes the dull disciple of thy school, That mild apostate from poetic rule, The simple Wordsworth, framer of a lay As soft as evening in his favourite May Who warns his friend `to shake off toil and trouble, And quit his books, for fear of growing double;' Who, both by precept and example, shows That prose is verse, and verse is merely prose; Convincing all, by demonstration plain, Poetic souls delight in prose insane; And Christmas stories tortured into rhyme Contain the essence of the true sublime. Thus, when he tells the tale of Betty Foy, The idiot mother of `an idiot boy'; A moon?struck, silly lad, who lost his way, And, like his bard, confounded night with day; So close on each pathetic part he dwells, And each adventure so sublimely tells, That all who view the `idiot in his glory', Conceive the bard the hero of the story. Crucial to Byron’s aesthetics; neoclassical tradition represents true poetry; the Lake Poets rejected it entirely for a completely false system which they used to promote their own intellects. „With regard to poetry in general I am convinced, the more I think of it, that … all of us – Scott, Southey, Wordsworth, More, Campbell and I – are all in the wrong, one as much as another –that we are upon a wrong revolutionary poetical system (or systems) not worth a damn in itself … . I am the more confirmed in this by having lately gone over some of our classics, particularly Pope … and I was really astonished (I ought not to have been so) and mortified at the ineffable distance in point of sense, harmony, effect, and even Imagination, passion, and invention, between the little Queen Anne’s man Pope and us of the lower Empire.”(Letter to his publisher, 1817) „It is the fashion of the day to lay great stress upon what they call „imagination” and „invention”, the two commonest of qualities: an Irish peasant with a little whiskey in his head will imagine and invent more that would furnish forth a modern poem.” (from Letters and Journals, 1819) 1809-1811: on a tour of Portugal, Spain, Gibraltar, Malta, Albania and Greece after his return he took his seat in the House of Lords and made his maiden speech on behalf of the stocking weavers; “I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces in Turkey, but never under the despotic of infidel governments did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return in the very heart of a Christian country.” (27 February 1812) II. 1812-1816 Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage Cantos I and II: written in Spenserian stanza it describes the travels and experiences of a pilgrim, who, sated with his past life of sin and pleasure, finds distraction in his travels through Portugal, Spain, Greece and Albania. Worse than adversity the Childe befell; He felt the fulness of satiety: Then loathed he in his native land to dwell, Which seem'd to him more lone than Eremite's sad cell. V For he through Sin's long labyrinth had run, Nor made atonement when he did amiss, Had sigh'd to many though he loved but one, And that loved one, alas! could n'er be his. Ah, happy she! to 'scape from him whose kiss Had been pollution unto aught so chaste; Who soon had left her charms for vulgar bliss, And spoil'd her goodly lands to gild his waste, Nor calm domestic peace had ever deign'd to taste. And now Childe Harold was sore sick at heart, And from his fellow bacchanals would flee; 'Tis said, at times the sullen tear would start, But Pride congeal'd the drop within his ee: Apart he stalk'd in joyless reverie, And from his native land resolved to go, And visit scorching climes beyond the sea; With pleasure drugg'd, he almost long'd for woe, And e'en for change of scene would seek the shades below. “Childe Harold is a sated epicure – sickened with the very fullness of prosperity – oppressed with ennui, and stung by occasional remorse; -- his heart hardened by a long course of sensual indulgance, and his opinion of mankind degraded by his acquintance with the baser part of them. In this state he wanders over the fairest and most interesting parts of Europe, in the vain hope of stimulating the palsied sensibility by novelty, or at least occasionally forgetting his mental anguish in the toils and perils of his journey.” (a contemporary critic in the Edinburgh Review) Identification of Byron with his persona fuelled interest in the poem and its author and aroused an unquenchable thirst (esp. in women) for information about his exploits and for more poetry dramatis persona: the Byronic hero (Byron provided his age with a “ruling personage: that is, the model that contemporaries invest with their admiration and sympathy”) first sketched in the first two Cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, then recurs in various guises in the verse romances and dramas to follow Alien, mysterious, gloomy spirit, superior in his passions and powers to the common run of humanity, whom he regards with disdain. He harbours the torturing memory of an enormous, nameless gilt that drives him toward an inevitable doom. Isolated, self-reliant, pursuing his own ends according to his self-generated moral code against any opposition, human or supernatural. Archrebel in a non-political form with a strong erotic interest. Literary descendants: Heathcliff (Wuthering Heights), Captain Ahab (Moby Dick), Pushkin’s Onegin. Forerunner of Nietzsche’s concept of the Superman, the hero who is not subject to the ordinary criteria of good and evil. 2 Consolidated his literary success by a series of Oriental tales (dark, brooding heroin exotic locations): The Giaour; The Bride of Abydos;The Corsair; Lara;The Siege of Corinth; Parisina; Hebrew Melodies (1815) a collection of short poems, many of them on scriptural subjects, some arranged to traditional Hebrew melodies; some remarkable love-songs (“She walks in beauty”) Immense popularity, (through his urging, his publisher published Kubla Khan, Christabel, The Pains of Sleep) idolized by women, sequence of liaisons with prominent ladies escape in marriage in 1815, disastrously illmatched, (huge depts, hysteric outbursts, infidelity and an allegedly incestuous relationship with his halfsister, Augusta; divorce in 1816, London alive with rumours of Byron’s private life: he is practically ostracized from society: left England forever on 25 April, 1816. III. 1816-1818 resumed travels (Bruges, Antwerp, Brussels and Waterloo) – experiences incorporated in Cantos III and IV of Childe Harold Geneva (from May till September 1816): he met Shelley: remarkable moment in literary history (not unlike the annus mirabilis of 1797-98 for Wordsworth and Coleridge) Childe Harold Canto III (this time written in 1st person singular, although for most of his life heartily contemptuous of Wordsworth, largely for having rejected Pope, for a brief period he listened to Shelley’s recitals of Wordsworth; Shelley “used to dose me with Wordsworth physic even to nausea” Where rose the mountains, there to him were friends; Where roll’d the ocean, thereon was his home; Where a blue sky, and glowing clime, extends, He had the passion and the power to roam; The desert, forest, cavern, beaker’s foam, Were unto him companionship; they spake A mutual language, clearer than the tome Of his land’s tongue, which he would oft forsake For Nature’s pages glass’d by sunbeams on the lake. (III,13) Reflections on the field of Waterloo; Napoleon portrayed with many of the characteristics of the Byronic hero Manfred (1816-1817) verse drama; most impressive representation of the Byronic Hero; Manfred, a Faustian figure, “half-dust, half-deity”, hounded by remorse over his incestuous relationship with Astarte, seeks oblivion. He tries to hurl himself from an alpine crag, but is dragged back by a hunter. He confesses his sin to the Witch of the Alps and descends to the underworld and sees a vision of Astarte, who promises him death. Back in his castle the abbot begs him to repent but he cannot. He rejects the offer a pact with the demons who summon him and when they vanish he dies. Abbot: “He is gone—his soul hath ta’en its earthless flight— / Whither? I dread to think – but he is gone.” Prometheus: the mythical character is a central influence over everything he wrote; a topic of discussion when he met Shelley in Geneva Thou art a symbol and a sign To Mortals of their fate and force; Like thee, Man is in part divine A troubled stream from a pure source … III. 1816-1818 left Switzerland for Venice Don Juan: satirical novel in ottava rima “I mean it for a poetical Tristram Shandy” , chief literary models: Italian seriocomic versions of medieval love romances; Tristram Shandy and Gulliver’s Travels The controlling element is not the narrative but the narrator; the poem is a continuous monologue “I want a hero: an uncommon want”; almost 2000 stanzas with shifts of mood and theme; T.S.Eliot: “What makes the tales interesting is first a torrential fluency of verse, and a skill in varying it from time to time to avoid monotony; and, second, a genius for digression. Digression, indeed, is one of the valuable arts of a story-teller. The effect of Byron’s digressions is to keep us interested in the story-teller himself, and through this interest to interest us more in the story.” a panorama of contemporary life; the narrator uses the occasion of Juan’s misadventures to confide to us his thoughts and devastating judgements on the major institutions, activities and values of Western society; a 3 series of skirmishes against the sexually prudish, religiously orthodox and politically conservative parties in England (“Let us have wine and woman, mirth and laughter, / Sermons and soda water the day after”) persistent joke that the archetypal homme fatal of European legend is more acted upon than is active (see, for instance, Canto I, Juan and Donna Julia) provoked an outrage as nothing in it is sacred, everything is reduced to the same materialistic level, everything is profane; copious absence of things sacred and respectable (e.g. Canto I, Stanzas 18-21; Julia’s farewell letter upstaged with Juan’s vomiting overboard) Satirical realism in exposing the hypocricy and corruption of high society But now I’m going to be immoral, now I mean to show things really as they are Not as they ought to be, for I avow That till we see what’s what in fact, we’re far From much improvement (XII) His publisher, who grew substantially rich from publishing Byron, through reluctantly published the first 5 cantos, drew back from Cantos VI-VIII “they were so outrageously shocking that I would not publish them if you were to give me your Estate—Title and Genius—For Heaven’s sake revise them”. Wordsworth on Don Juan: “I am persuaded that Don Juan will do more harm to the English character than anything of our time” (Byron is a “monster … a Man of Genius whose heart is perverted”) Byron on Don Juan: “˝I maintain that it is the most moral of poems; but if people won’t discover the moral, that is their fault, not mine.” Of the great contemporaries only Shelley is appreciative: “every word of it is pregnant with immortality” Don Juan left unfinished by Byron’s untimely death in the fight for Greek Independence “Why I came here I know not, where I shall go to, it is useless to inquire. In the midst of myriads of the living and dead worlds – stars – systems – infinity –why should I be anxious about an atom.” PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY (1792-1822) Shelley “has a fire in his eye, a fever in his blood, a maggot in his brain, a hectic flutter in his speech, which mark out the philosophic fanatic. He is sanguine complexioned, and shrill-voiced. … He is clogged by no dull system of realities, no earthbound feelings, no rooted prejudices, by nothing that belongs to the mighty trunk and hard husk of nature and habit, but is drawn up by irresistible levity to the regions of mere speculations and fancy, to the sphere of air and fire, where his delighted spirit floats in ‘seas of pearls and clouds of amber’.” (Hazlitt :’On Paradox and Commonplace’) radical nonconformist from a solidly conservative background; father:baronet and Whig MP Eton (1804-1810): thorough grounding in the classics; became interested in science (electricity, magnetism, chemistry, telescopes) and radical political and philosophical ideas (Thomas Paine, William Godwin) University College, Oxford: expelled after 6 months because of his pamphlet, The Necessity of Atheism, which he mailed to the bishops and heads of colleges. He claimed that God’s existence cannot be proved on empirical grounds and that “Truths has always been found to promote the best interests of mankind. Every reflecting mind must allow that there is no proof of the existence of a Deity.” Eloped to Edinburgh to marry 16-year-old Harriet Westbrook, estrangement from his father, political pamphlets for Catholic emancipation and for the amelioration of the oppressed and poverty-stricken people of Ireland Queen Mab (1813) first important work (institutional religion and codified morality are the roots of social evil; prophesies that all institutions will wither away and humanity will return to its natural condition of goodness and felicity) Elopement with Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin while still married– general opinion of him as atheist, revolutionary and gross immoralist 1818—moves to Italy, he envisions himself as an alien and outcast, rejected by the human race to whose welfare he dedicated his powers and his life. 4 Intellectual maturity: 1816-1822 “I always seek in what I see the manifestation of something beyond the palpable” (Shelley in a letter to Thomas Love Peacock) His poetry takes its point of departure from his immediate predecessors Wordsworth and Coleridge (although he claimed to be an atheist, the pantheistic life-force behind Tintern Abbey and Immortality Ode had tremendous impact on his poetry) and is deeply rooted in Plato and Neoplatonism 1816 in Geneva with Byron: intellectual and creative collaboration Mont Blanc (1816): “local” poem; major influence is Tintern Abbey; landscape: emblem of the human mind; Shelley’s position about the creator: “awful doubt”, a feeling of awe for the power (sometimes frighteningly destructive) evident in the natural world, mixed with skepticism as to whether it reveals a divine presence. 16 August 1819, “Peterloo” (On St Peter’s Field, near Manchaster the political meeting of 60.000 working men and women dispersed by mounted dragoons with a brutality that left a lot of people dead or seriously wounded. Shelley’s outraged response was quick: Song to the Men in England Sonnet: England in 1819 The Mask of Anarchy greatest poem of political protest in the language, satire medieval dream allegory with surrealistic effects Murder: Castelreigh (Foreign Secretary) Fraud: Eldon (Lord Chancellor) Hypocricy: Sidmouth (Home Secretary) Anarchy (the idol pf both the government and the people) Stanzas 34-63: a maid who has risen up to halt Anarchy, addresses the crowd, telling them of false and then of true freedom; in the concluding section she calls on them to stand up for their rights using passive resistance: Stand ye calm and resolute, Like a forest close and mute With folded arms and looks which are Weapons of an unvanquished war; … With folded arms and steady eyes, And little fear, and less surprise, Look upon them as they slay, Till their rage has died away. … Rise like lions after slumber In unvanqushable number; Shake your chains to earth like dew Which in sleep had fallen on you— Ye are many, they are few. Ode to the West Wind (October 1818) a month after The Mask of Anarchy; 5 sonnet-like verse paragraphs in terza rima Statement of faith in the ability of human beings to resist the oppression of church and state, and to realize their power of self-determination; a call on the ‘pestilence-stricken multitudes’ to participate in the millennial vision of ‘new birth’; the poem goes further than that: it insists on the primacy of the poet as the central agency, the saviour-like prophet, who will awaken the masses to their potentians … Be thou, Spirit fierce, My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one! Drive my dead thoughts over the universe Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth! And, by the incantation of this verse, Scatter, as from an unextinguished hearth Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind! Be through my lips to unawakened Earth The trumpet of prophecy! O Wind If winter comes, can Spring be far behind? 5 Prometheus Unbound (1818-19) lyrical drama, literary predecessors: Aeschylos (Prometheus Bound), Milton (Paradise Lost) and Byron (Manfred) partly psychodrama, partly political allegory; several levels of interpretations: political, scientific, psychological and spiritual; simultaneously external and internal reflections impressive variety of verse forms: rhetorical soliloquies, dramatic monologues, love-songs, dream visions, lyric choruses and prophecies Mary Shelley: “That man could be so perfectionised as to be able to expel evil from his own nature and from the greater part of the creation, was the cardinal point of his system.” Prometheus: remaking of the poet-figure of the Ode to the West Wind; stands for the desire in the human soul to create harmony through reason and love; when love and reason are united, evil is doomed A Defence of Poetry (1821, publ. 1840) “A poet participates in the eternal, the infinite, and the one; as far as relates to his conceptions, time and place and number are not. … A poet is a nightingale who sits in darkness and sings to cheer its own solitude with sweet sound. … Poets are hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futuriry casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they aspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Adonais (1821) elegy on Keats’s death (Moschus: Elegy for Bion, Milton: Lycidas) 55 Spenserian stanzas Keats (Christ-like figure, doomed and neglected, suffering for the benefit of art) is lamented under the name Adonais, Greek god of beauty and fertility; Belief in Neoplatonic resurrection in the eternal beauty of the universe: He is made one with Nature: there is heard His voice in all her music, from the moan Of thunder, to the song of night’s sweet bird, He is a presence to be felt and known In darkness and in light, from herb and stone, Spreading itself where’er that Power may prove Which has withdrawn his being to his own, Which wields the world with never-wearied love, Sustains it from beneath, and kindles it above. Tragically early death on 7 July 1822 (sudden storm sunk their boat Don Juan/Ariel) Last, unfinished work, The Triumph of Life breaks off with a question: Then what is life? I cried. John Keats (1795-1821) “I am certain of nothing but of the holiness of the Heart’s affections and the truth of Imagination – What the Imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth – whether it existed before or not.” (Keats’s letter; 22 November 1817) Keats's letter to Shelley: “A modern work, it is said, must have a purpose which is God. An artist must serve Mammon...You, I am sure, will forgive me for sincerely remarking that you might curb your magnanimity and be more of an artist, and load every rift of your subject with ore.” (August 1820) Influence of Spenser (Epithalamion, The Faerie Queene), Milton, Dante, Shakespeare Keats's letter to Reynolds (22 Nov. 1817) "One of the three books I have with me is Shakespeare's Poems: I never found so many beauties in the Sonnets--they seem to be full of fine things said unintentionally--in the intensity of working out a conceit. Is this to be borne? Hark ye! When lofty trees I see barren of leaves Which erst from heat did canopy the herd And Summer's green all girdled up in sheaves, 6 Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard. He has left nothing to say about nothing or anything..." + Influence of painting (Poussin, Claude Lorrain, Titian) + Influence of Hellenism (“religion of joy”) Elgin marbles (Sonnet: On First Seeing the Elgin Marbles) Lemprière’s Classical Dictionary Homer On First Looking into Chapman's Homer (Oct. 1816) Much have I travelled in the realms of gold, And many goodly states and kingdom seen; Round many western islands have I been Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold. Oft of one wide expanse have I been told That deep-browed Homer rules as his demense; Yet did I never breath its pure serene Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold. Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken; Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes He stared at the Pacific, and all his men Looked at each other with a wild surmise Silent, upon a peak in Darien. Sleep and Poetry (Oct.1816) Stop and consider! Life is but a day; A fragile dew-drop on its perilous way From the tree’s summit; a poor Indian’s sleep While his boat hastens to the monstrous steep Of Montmorenci. Why so sad a moan? Life is the rose’s hope while yet unblown; The reading of an ever-changing tale; The light uplifting of a maiden’s veil; A pigeon tumbling in clear summer air; Alaughing school-boy, without grief or care, Riding the springy branches of an elm… I Stood Tip-Toe Upon a Little Hill … Open afresh your round of starry folds, Ye ardent marigolds! Dry up the moisture from your golden lids, For great Apollo bids That in these days your praises should be sung On many harps, which he had lately strung; And when again your dewiness he kisses, Tell him, I have you in my world of blisses: So haply when I rove in some far vale His mighty voice may come upon the gale!.. Endymion (1817) A thing of beauty is a joy for ever, Its loveliness increases, it will never Pass into nothingness; but still will keep A bower quiet for us, and a sleep Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing. ANNUS MIRABILIS: September 1818-September 1819 Death of Tom Keats + King Lear (Sonnet: On Sitting Down to Read King Lear Once Again) 7 Letter (19 February, 1819): "...circumstances are like clouds continually gathering and bursting - while we are laughing the seed of some trouble is put into the arable land of events." The Eve of St Agnes La Belle Dame Sans Merci Ode to Psyche Ode to a Nightingale Ode on a Grecian Urn Ode on Indolence On Melancholy Hyperion – The Fall of Hyperion Letter from Winchester, 21 Sept. 1819: How beautiful the season is now--How fine the air. A temperate sharpness about it. Really, without joking, chaste weather--Dian skies--I never lik'd stubble fields so much as now--Aye better than the chilly green of spring. Somehow a stubble plain looks warm...this struck me so much in my sunday's walk that I composed upon it. To Autumn Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness, Close bosom friend of the maturing sun, Conspiring with him how to load and bless With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run: To bend with apples the mossed cottage-trees, And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core; To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells With a sweet kernel; to set budding more, And still more, later flowers for the bees, Until they think warm days will never cease, For summer has o'er-brimmed their clammy cells. Where are the songs of spring? Aye, where are they? Think not of them, thou hast thy music too-While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day, And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue. Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn Among the river sallows, borne aloft Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies; And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn; Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft; And gathering swallows twitter in the skies. (September, 1819) Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store? Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find Thee sitting careless on a granary floor, Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind; Or on the half-reaped furrow sound asleep, Drowsed with the fume of poppies, while thy hook Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers; And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep Steady thy laden head across a brook; Or by a cyder-press, with patient look, Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours. 27 Oct. 1818: As to the poetic character itself (I mean that sort of which, if I am anything, I am a member; that sort distinguished from the Wordsworthian or egotistical sublime...) it is not itself - it has no self - it is everything and nothing - it has no self - it has no character - it enjoys light and shade, it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated - It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosopher delights the chameleon poet. It has no harm from its relish of the dark sides of things any more than from its taste for the bright one; because they both end in speculation. Sleep and Poetry ...A drainless shower Of light is Poesy; 'tis the supreme power; 'Tis might half-slumbering on its own right arm. (235-7) King Lear: V.2. Men must endure Their going hence even as their coming hither: Ripeness is all. 8