PHM 421Y (Pharmaceutical Care III) – Seizure Disorders

advertisement

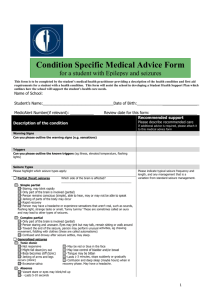

PHM 421Y (Pharmaceutical Care III) – Seizure Disorders Case A 10-year-old boy (35 kg) has recently been documented as having complex partial with secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures. These recurrent seizures were initially treated with valproic acid 250 mg bid, which was gradually increased weekly by 5 mg/kg/day until the child received 2000 mg/day (maximum recommended dose) in 4 divided doses. Despite increasing the dose from 1500 mg to 2000 mg/day, the serum valproate levels only increased from 500 to 600 mol/L (therapeutic range: 350-700 mol/L) and the child continued to have seizures. Elevations in liver transaminases and LDH were reported. Valproate was immediately discontinued and carbamazepine 200 mg bid started. After the first week, only 1 seizure was observed (previously 3/week) and the carbamazepine serum trough level was 30 mol/L (therapeutic range: 17-50 mol/L). A repeat level was obtained at Week 3 when the patient had a second witnessed seizure (serum level at this time was 17 mol/L). The dosage was slowly increased, but the child complained of double vision, drowsiness, headaches and continuing seizures. The dose of carbamazepine was reduced, the drug-related adverse effects disappeared, but after 2 months of therapy, the patient continues to have seizures (2/week). At this point in time, the addition of a second drug is being considered as adjunct therapy for refractory seizures. One of the parents has a drug plan through their place of employment. The patient has no known allergies, and is presently not receiving any other medications. Drug costs (approximate costs per month for standard dosages): Phenytoin: Valproic Acid: Vigabatrin: Gabapentin: Fosphenytoin: Legend: $ $$-$$$$$ $$$$-$$$$$ $$-$$$$ $$$$$ (Status) $ (<$20) Phenobarbital: Ethosuximide: Clobazam: Lamotrigine: Oxcarbazepine $$ ($20-50) $ $-$$$ $-$$$ $$-$$$$ $$$-$$$$$ $$$ ($50-70) Carbamazepine: Clonazepam: Primidone: Topiramate $ $ $ $$$$$ $$$$ (75-100) $$$$$ (>$100) Required Readings: Lott RS and McAuley JW. Seizure disorders. In: Koda-Kimble MA and Young LY (editors). Kradjan WA and Guglielmo J (assistant editors). Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs. 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001. pp 52-1 – 52-41. Recommended Readings: Gidal BE, Garnett WR, Graves N. Epilepsy. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC et al (editors). Pharmacotherapy – a pathophysiologic approach. 5th edition. New York, McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division, 2002, pp. 1031-59 (Excluding felbamate, pp 1045-6). Brian Hardy, Pharm.D. November 13, 2002 PHM 421Y (Pharmaceutical Care III) – Seizure Disorders Learning Objectives 1. To become familiar with the long-term treatment of localization-related (partial/focal) and generalized –onset seizures. 2. To become familiar with conventional therapy and new anticonvulsants for the adjunct management of refractory epilepsy. PHM 421Y (Pharmaceutical Care III) – Seizure Disorders Common Drug-Related Problems 1. For many known (e.g. intolerance, ADRs, frequency of administration, lack of convenience, drug-drug interactions, drug expense, etc.) and unknown reasons, lack of compliance remains a common cause for the therapeutic failure. 2. It is not uncommon to see patients who are failing to have adequate seizure control being prescribed 2 or more anticonvulsants. Most of these drugs or their metabolites interact (e.g. hepatic induction, hepatic inhibition, protein binding displacement), which requires adjustments in drug dosages, close and frequent monitoring for toxicities/symptoms, and when available, serum drug levels (total and/or free). 3. Controversy exists about whether attempts should be made to withdraw drug therapy in patients who have been seizure-free for extended periods of time. Guidelines for risk assessment exists for children and/or adults who have epilepsy and have been seizure-free for 2 years. Recommendations have also been made about the duration of therapy in head trauma or post-craniotomy patients. 4. The use of anticonvulsant therapy in women during pregnancy (i.e. teratogenicity) is a recurrent risk-benefit assessment DRP. 5. Status epilepticus in a serious acute neurological emergency. Failure to quickly and effectively treat these patients may result in severe morbidity (e.g. brain damage) or mortality. PHM 421Y (Pharmaceutical Care III) – Seizure Disorders Key questions you should be able to answer 1. What were the relevant (real and potential) drug-related problems this patient presented with? 2. What presently is the patient’s main drug-related problem? 3. What signs and symptoms were experienced by this patient? How do these compare to those S & S observed in patients with partial complex seizures and secondarily generalized seizures? How else may seizure disorders present (i.e. according to seizure classification)? 4. What are the general risk factors (i.e. etiology) for seizure disorders? 5. What other diseases or disorders (i.e. including drug-related causes) need to be “ruled-out” in the differential diagnosis of seizure disorders? 6. Do all patients who have seizures require treatment? How do you decide? 7. What therapeutic options are available for patients with seizure disorders (i.e. what treatments are available for the various seizure classifications)? 8. What are the advantages and/or disadvantages of each of these treatments (i.e. create a therapeutic alternative chart)? 9. What specific treatment would you select for the patient presented in the case? Justify your answer. 10. What would you directly or indirectly take responsibility for in the management of this patient (i.e. develop a pharmacy care plan)?