An Issues Paper - HKU Libraries

advertisement

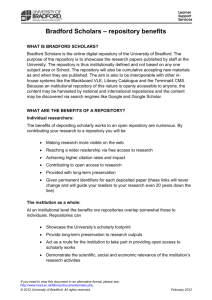

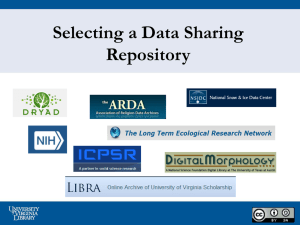

An Institutional Repository for the University of Hong Kong: An Issues Paper 16 January 2004. The Institutional Repositories Taskforce: A Taskforce of the Knowledge Team A The Brief. This taskforce was convened to study the Institutional IT/Knowledge Repositories issue. Specifically the taskforce will look at LEARNet and other similar projects to see if the University of Hong Kong should, like many institutions elsewhere (including HKUST) take advantage of the open source software platform phenomenon that enables institutions to: (1) capture and describe digital works using a submission workflow module, (2) distribute an institution's digital works over the web through a search and retrieval system, and (3) preserve digital works over the long term. Following its first meeting and a report to the Knowledge Team, the Taskforce was asked to provide an issues paper outlining some of the major issues surrounding the introduction of an institutional repository at the University. B What is an Institutional Repository? As a recent, emerging concept it is not an easy task to precisely define what constitutes an institutional repository. In what is arguably the most significant article dealing with institutional repositories to date, Clifford Lynch (2003) provides a broad definition of what he believes an institutional repository to be. In particular, he states, they provide: …for the management and dissemination of digital materials created by the institution…an organizational commitment to the stewardship of these digital materials, including long-term preservation…as well as organization and access or distribution…the management of technological changes, and the migration of digital content from one set of technologies to the next… a mature and fully realized institutional repository will contain the intellectual works of faculty and students—both research and teaching materials—and also documentation of the activities of the institution itself in the form of records of events and performance and of the ongoing intellectual life of the institution. (Lynch, 2003, p. 328). The Ohio State University’s (OSU) Knowledge Bank provides another interesting perspective on what an institutional repository might be. While the OSU Knowledge Bank’s original purpose was “to collect, to index, and to preserve digital content produced by faculty” (Rogers, 2003, p. 126), this definition was broadened to include “the full array of digital assets and information services available to or being created by OSU faculty, staff and students” (emphasis added), (Rogers, 2003, p. 126). The introduction of digital content available to the institution in the latter definition raises a host of complex issues that, it appears, other institutions with these repositories have chosen not to tackle. The OSU Knowledge Bank is still in the planning stages, -1- insofar as only a central listing of OSU digital projects is being collated (Ohio State University Library, 2003). Essentially an institutional repository is defined by the institution itself. Specifically the material to be included in the repository will vary among institutions but these must be digital, searchable and wide ranging in their nature. The institution must also make a commitment towards preservation of the material and perpetual access ensuring that material is not deleted after a certain amount of time but continues to be built upon. C The Situation at the University of Hong Kong. LEARNet. The University has contributed descriptions of learning objects to the Learning Resource Catalogue (LRC), created by the University of New South Wales as a Universitas21 initiative, for several years. This catalogue of learning objects is shared among U21 member institutions who are in most cases free to reuse relevant objects that they locate through the catalogue. As an extension of this programme the University through its CAUT sought to extend this resource sharing among all UGC funded institutions. With UGC funding the LEARNet project was established. LEARNet enables the University, through the use of the U21 software, to share its learning objects with both other U21 institutions as well as other UGC funded institutions. Conversely however, other U21 institutions are blocked from viewing other UGC records and other Hong Kong universities are blocked from accessing U21 institution records with the exception of the University of Hong Kong who shares with both. Setting up this environment has been a complex task made possible through the UGC grant which will expire at the end of 2004. The University of Hong Kong has made a significant investment in this project and remains committed to its success. How does LEARNet differ from an institutional repository? Firstly the LEARNet catalogue (LRC) is just that, a catalogue. It is not a repository. The objects are described using learning object metadata (LOM) and a link is usually provided to where the item can be retrieved. Learning objects themselves are described as building blocks for teaching and learning purposes that are self-contained, shareable, searchable, reusable and can be updated. So while it might be attractive to use the LEARNet project as a springboard for an institutional repository, it can be seen that the focus of LEARNet is far too restrictive in its purpose and if used as an institutional repository would serve to limit its applicability to other digital materials. Ideally, however, if an institutional repository is adopted at the University a high degree of interoperability or record duplication across the two systems would be necessary as these materials should form a significant part of such a repository. Registry’s Research and Scholarship Database. This database, collated annually, highlights significant research activities conducted by Faculty as well as providing an overview of each Faculty's research directions (HKU Registry, http://www.hku.hk/rss/rs2002/index.html). Each Faculty Profile also provides entries on individual researchers in each Department under the Faculty. These entries describe information about research projects and research outputs as -2- well as titles of theses produced in that academic year by research postgraduate students. In 2002 the Libraries worked with the Registry and the Computer Centre to provide links between the database and the electronic journals to which the Libraries subscribe. This database, while only providing descriptions and in some cases a link to the published material, provides a significant variety of University output which, if available in full text, could form the basis of an institutional repository. The Libraries’ Hong Kong University Theses Online. This collection comprises more than 8,000 titles of theses and dissertations submitted for higher degrees to the University of Hong Kong since 1941. Of these titles only a small number is available in full-text (59 at time of writing) with the remainder containing metadata descriptions as well as contents and abstracts. Once again the content of this database would make a major contribution to a University institutional repository. Other resources in faculties, departments, administrative divisions? This is the great unknown. It is believed that some University Departments currently digitise their departmental records but it is uncertain which records are digitised, how they are stored and whether they are retained indefinitely or destroyed after a certain number of years. The Libraries’ Administration Department, for example, digitises its administrative records, letters and so on and utilises the Document Imaging System developed by the Computer Centre and available through the Staff Intranet for storage and retrieval. D Why Introduce an Institutional Repository? ‘Superarchives’ could hold all scholarly output’ (Young, 2002) was how the Chronicle of Higher Education chose to pronounce the rise of institutional repositories. While ostensibly positive in its by-line, Young’s article also raises a degree of scepticism concerning the likely success of such repositories citing earlier failed attempts at ‘widespread reform of academic publishing’ (Young, 2002, p. A30). The changing scholarly publishing environment. The Scholarly Publishing & Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC, 2002, p. 5) believes that the impact of several coinciding factors make this the right time for a new scholarly publishing environment. Specifically among these are: Technological change in digital publishing and networking has driven the demand for more robust digital presentation Marked increases in research output (particularly in the sciences) is straining the capacity of the print publishing model Increasing dissatisfaction with traditional print and electronic journal pricing and marketing models Increasing uncertainty and concern over digital preservation of digital scholarly material. Institutional repositories capture the intellectual output of a university. They also have the potential to enable a university to form part of the rapidly growing global network of repositories who have the ability to be interoperable thus providing a new -3- disaggregated model of scholarly publishing. Institutional visibility and prestige. All universities pride themselves on their intellectual output. With its significant output in both quantity and quality, the University of Hong Kong is no different. By aggregating its intellectual output in an institutional repository, the University is in a position to more readily demonstrate its prestige through its quality output and in turn its value to society. Such demonstration has the opportunity to translate into real benefits including funding from both private and public sources. Preservation. As the nature of scholarly communication changes universities are seeing academics and other researchers developing research and teaching materials in increasingly complex digital formats. The need to collect, store, arrange and disseminate this material is a complex task and one that runs the risk of significant duplication and therefore cost if not conducted at an institutional level with institutional commitment. But digital preservation is a complex matter and one that most institutional repositories have not yet dealt with in any satisfactory manner. The SPARC institutional repository checklist & resource guide (SPARC, 2002a) highlights this when it says that ‘many of the early institutional repository implementations have deferred decisions about long-term digital preservation’ and that this is in anticipation of progress being made ‘in terms of developing standards for digital preservation’ (p. 38). Other (prestigious) universities are doing it. While participation based on others involvement is not without flaws, it is noteworthy to highlight some of the Universities now involved in institutional repositories or some derivation of them. Perhaps the best known is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Library who partnered with Hewlett-Packard to develop the DSpace software now implemented there and being tested, adopted or adapted in other institutions including Cambridge University, Ohio State University, Columbia University, Cornell University, the University of Rochester, the University of Toronto, and the University of Washington at Seattle. In Hong Kong the University of Science and Technology has also implemented DSpace, albeit with a limited number of items currently available (279 titles at the time of writing). E Problems with Introducing an Institutional Repository. Several issues need to be addressed in order to successfully implement an institutional repository at the University of Hong Kong. What to include – the need for a local definition. Contingent upon any discussion to implement an institutional repository is the need for an institutional definition of its repository, in particular what types of digital material will be contained within the repository. As we have seen, Clifford Lynch provides a fairly broad definition that encompasses intellectual works of faculty and students, both research and teaching materials as well as documentation of the activities of the institution. The taskforce believes that should a HKU institutional repository be established, it should only hold material of scholarly value, and not -4- administrative documentation such as departmental minutes. The Ohio State University definition includes not only digital material created by the institution but also digital material available to the institution. Through its publications, SPARC tends to emphasize the research output of the university and as an alternative to more traditional scholarly publishing methods. Another aspect of the definition that must be considered early is whether the institution is willing to share its resources beyond its immediate members. While part of the spirit of the institutional repository is to enable greater scholarly communication, this does not prohibit the institution from restricting access to certain kinds of material housed in the repository. As an example, the MIT has blocked external full-text access to its MIT Press publications. Faculty participation. Needless to say but Faculty involvement is critical to the success of an institutional repository. In particular if faculty are asked to use the repository as an alternative means of publishing their scholarly output, they need to be convinced that this alternative is viable, promotes scholarship in their disciplines and indeed brings them the prestige afforded by publishing in refereed established journals. If the repository is to be used for traditionally unpublished material, this is less of a concern but faculty still need to understand the benefits of sharing these materials. Non-faculty participation. The successful institutional repository will not only enjoy faculty participation but also non-faculty participation. Once again institutional requirements will dictate which non-faculty departments are required to be involved. Certainly the Libraries and the Computer Centre and most likely the Press, the Registry and the Museum will need to be involved. Potentially all administrative and service departments will make some contribution. Engaging such an extensive range of players will require a strong commitment from the University administration. Coordinating such a group is also not without its problems. How to implement. Extensive implementation does not yet appear to be a reality in any of the institutions with institutional repositories. Even MIT as leaders of DSpace have a limited number of departments contributing to the repository. Their strategy may be to roll out the software to only a select number of departments in order to identify further issues and problems and when these have been dealt with to hold up the successful implementation to other departments. This is most likely a suitable strategy for the University of Hong Kong to adapt. Costs. While institutional repository software is open source and freely available, this does not mean that there are no costs involved in such an implementation. These are predominantly in the form of staffing and hardware. MIT estimates annual cost to maintain DSpace at US$285,000 ($225,000 staffing; $25,000 operating expenses; $35,000 system equipment). -5- Timing – should we wait and see? Institutional repositories have attempted to set themselves apart from earlier failed attempts at alternative academic publishing efforts. To some extent this could be seen as successful as they can be distinguished from those earlier attempts with new institutions participating and their attempt to collect a wider range of materials. Yet the question remains whether or not the scholarly community is ready to embrace the institutional repository as an alternative to traditional academic publishing. Extensive adoption of this software and the participating institution’s commitment to sharing the content contained within will judge the success of institutional repositories as an alternative publishing means. If the University chose to implement a repository that is a restricted, internal, central repository of the University’s digital output, then the success relies largely upon a University wide commitment to the project. Joe Branin’s Visit F In early December taskforce members attended presentations by Joe Branin, Director of Libraries at the Ohio State University where the development of the Knowledge Bank, an extensive repository and referatory, is currently under development and receiving much coverage. The taskforce also met with Joe Branin on Friday 5th December where we were able to discuss many of the issues raised in this paper and gain a first hand account of the evolution of the Ohio State University Knowledge Bank. The Ohio State University Knowledge Bank The Ohio State Knowledge Bank is far more than an institutional repository and, as Branin himself admitted, might be more ambitious than their ability to deliver. The Bank will consist of a number of components, namely: • • • • • • • • Online Published Material – E-books, e-journals, government documents, handbooks Online Reference Tools – Catalogs, indexes, dictionaries, encyclopedias, directories Online Information Services – Scholar’s portal, alumni portal, chat reference, online tutorials,, ereserves, e-course packs, technology help center Electronic Records Management Administrative Data Warehouse Digital Publishing Assistance – Pre-print services – E-books, e-journal support – Web site development and maintenance Faculty Research Directory Digital Institutional Repository – Digital special collections – Rich media (multimedia) – Data sets and files – Theses/dissertations – Faculty publications, pre-publications, working papers – Educational materials • Learning objects -6- • • • Course reserves/E-course pack materials • Course Web sites Information Policy Research/Development in Digital Information Services – User needs studies – Applying best practice – Assistance with Technology Transfer Such an undertaking is indeed ambitious and it would be difficult to imagine a similar undertaking being successfully introduced here at the University of Hong Kong. Implementation at Ohio State University The mandate for the OSU Knowledge Bank was received from the Office of the President where a senior member of the University has championed what they believe is a worthy project. As Director of the Library, Joe Branin was asked to make this happen. Branin indicated that the starting point for OSU would be the establishment of a Faculty Research Directory and that considerable interest was generated at their institution for the development of this expertise database. Branin also reported that the Knowledge Bank will not include traditionally published scholarly literature, nor their pre-prints. The OSU faculty was not interested in this idea, and some were adamantly opposed. While OSU are adopting MIT’s open source DSpace, there are still considerable startup costs involved in doing this. Apart from the necessary hardware and technical support, OSU have employed a full time project manager whose role is to 1) gain university wide acceptance, indeed commitment, for the Knowledge Bank and 2) identify appropriate resources to be contained within the Bank and seek the relevant approval for doing so. There are obvious difficulties in HKU following the OSU model of implementation. G The Options for HKU Taskforce members agree there is great merit in introducing an institutional repository at the University of Hong Kong. In the interests of 1) making accessible material that is hidden away or accessible to only a few, 2) contributing to open scholarly communication, and 3) establishing a commitment to long term preservation of resources, the taskforce commends to the Knowledge Team four possible options for its consideration: 1 Undertake a full implementation of DSpace (or other similar package) with a full approach, similar to the OSU model. This option provides for a fuller implementation of a repository than option 2, along similar lines to the OSU model as espoused by Joe Branin. This model would require a major commitment from the University in terms of both resources and support for the project. There is obviously substantial risk in adopting this option as a considerable outlay of resources would be necessary for any successful implementation. The likelihood of success in such a full scale implementation is -7- limited as a considerable outlay of resources, and perpetual commitment of renewal of those resources, would be necessary. 2 Implement DSpace (or other similar package) with a ‘soft’ approach. This option suggests that DSpace (or other similar package) be implemented and that a department or departments be asked to contribute working papers and other unpublished material into the repository. If this is successful it can be held as a model and used to encourage others to contribute. It should be stressed that the taskforce did not undertake any significant assessment of DSpace or any of the other repository packages and that such an assessment should be done prior to any implementation. 3 Develop an effective institutional search engine. In option 3 wide-scale implementation would dictate that the resources mentioned in section C, above, would be included in the repository. Each of these resources is unique and can currently be accessed independently to meet a particular need. The benefit of incorporating these into a single repository enables a single search to be undertaken across all at once. In doing so these sets of data may lose their individuality and become part of a larger set of potentially incongruous data. The development of a HKU institutional search engine as opposed to a “fixed” institutional repository that enables the user to choose the sets of data that they wish to search then to conduct a single search across those datasets would serve the same purpose as a repository whose principal function is to provide integrated searching. One example of such a search engine is the MetaFind service recently implemented by HKU Libraries <http://metafind.iii.com/muse/servlet/MusePeer?action=logon&userID=uhk&userPw d=uhk&templateFile=search/search.html&pageId=asearch>. This search engine will search across several discrete databases or repositories, such as ScienceDirect, LexisNexis and Inspec. It could also be made to search across HKU's local databases in conjunction to the aforementioned repositories, or in isolation from them. Another example is the Open Archive Initiative (OAI) service providers. Metadata could be harvested from the several HKU repositories, and included in one or several of them, to enable searching across HKU repositories in conjunction to other non-HKU repositories, or in isolation from them. One OAI service provider is ARC at Old Dominion University, <http://arc.cs.odu.edu:8080/oai/advanced_search.jsp>. It is worthy to note that the HKU Theses Online (HKUTO) is already searchable in ARC. 4 Adopt a wait and see approach. The concept of an institutional repository is a relatively recent phenomenon. However tracking further developments in this area, in particular which models of implementation, which hosting software, and which definition of IR content are most successful, will provide the University with a greater degree of certainty in any future implementation. H Conclusion Members concurred that any institutional repository for HKU should, at least in the first instance, only hold material that is of scholarly value. With this precondition, taskforce members agree that option 1, based on the OSU model, is inappropriate. -8- Furthermore this option presents a high financial risk, particularly as we lack the clarity of commitment from the wider University community for such an undertaking. Option 2 provides a more realistic approach for the HKU situation and in fact seems to be quite representative of most current models of implementation, with the obvious exception of that at OSU. This option is also not without risk, albeit on a smaller scale than the previous option. Testing the DSpace platform, identifying a relevant department with appropriate material, purchase of hardware and dedicating technical staff must all be considered. Option 3 provides for a technology that has been tested and proven effective. It will allow present HKU initiatives to continue on their present course. These include the aforementioned Research & Scholarship database linking, HKUTO, and others such as the Library’s ExamBase, Sun-Yat sen in Hong Kong, etc. It will allow these existing databases and repositories, and future ones, to maintain their separate and unique identities, as well as give the user the opportunity to search, at one go, across all of them. Option 3, compared to Options 1 and 2, is much less labour/cost intensive. It is also an option that could be a stepping stone for us; ie, allow us to offer meta-searching across many HKU repositories now, but allow the opportunity in the future to once again consider options 1 and 2, perhaps after more defining developments have occurred and the field comes into better focus. Option 4 provides the University with the time to witness the relative success of the various models of implementation, software platform and content definition and to base our implementation on the most successful of these. Perhaps underpinning any final decision is the need to firstly determine our own rationale for desiring an institutional repository for the University of Hong Kong. Having identified this rationale, the choice of options and the definition of material to be included may be made with greater confidence. -9- I Summary of Options: Pros and Cons Option 1 Undertake a full implementation of DSpace (or other similar package) with a full approach, similar to the OSU model. Pros Greatest possible single point of access to university digital information. Cons Much material may be of minimal value and not warrant the effort. We already have several components that could be included. These unique components lose their identity. Requires ongoing commitment from many areas of the University – uncertainty that such commitment will be forthcoming. High cost and therefore financial risk. 2 Implement DSpace (or other similar package) with a ‘soft’ approach. 3 Develop an effective institutional search engine. Need only identify a single department to contribute materials. Provides a test-bed environment with only minor risk. Most institutions implementing IRs are adopting this method. Proven technology. Low cost and maintenance. Allows existing databases and repositories, and future ones, to maintain their separate and unique identities. - 10 - Few other implementations of this kind to learn from. Need to identify that department Some financial risk (purchase of hardware and dedicating technical staff must all be considered), but lower than option 1. University not seen at the forefront of the IR movement. 4 Adopt a wait and see approach. Requires little immediate effort. Enables an analysis of models of implementation, hosting software, and definition of IR content that are most successful Taskforce members Colin Day, Press Clara Ho, Press MC Pong, Computer Centre David Palmer Libraries Tina Yee-wan Pang, Museum and Art Gallery Peter Sidorko (Chair), Libraries. - 11 - University not seen at the forefront of the IR movement. References Lynch, C. A., 2003, Institutional repositories: Essential infrastructure for scholarship in the digital age. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 3(2) pp. 327-336. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Library, 2002, DSpace durable digital repository: definition <http://dspace.org/what/definition.html>. Ohio State University Library, 2003, Digital projects at the Ohio State University, <http://dlib.lib.ohio-state.edu/DISC/academics.php>. Rogers, S.A., 2003, Developing an institutional knowledge bank at Ohio State University: From concept to action plan. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 3(1) pp. 125-136. Scholarly Publishing & Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC), 2002, The Case for institutional repositories: a SPARC position paper, prepared by R Crow, SPARC, Washington, DC, available at <http://www.arl.org/sparc/IR/IR_Final_Release_102.pdf>. Scholarly Publishing & Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC), 2002a, SPARC institutional repository checklist & resource guide, prepared by R Crow, SPARC, Washington, DC, available at <http://www.arl.org/sparc/IR/IR_Guide_v1.pdf>. Young, J. R., 2002, 'Superarchives' could hold all scholarly output. Chronicle of Higher Education, 48(43) pp. A29-A30. (c:\mmy\knowledge-team\institutional-repository-for-hku-issue-paper) - 12 -