Matthew Woodcock - University of Warwick

advertisement

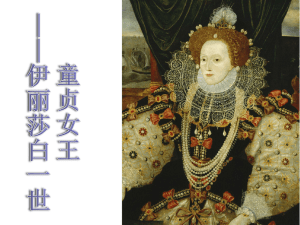

Susan Doran and Thomas S. Freeman, eds., The Myth of Elizabeth. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. x + 269 pp. ISBN 0333930843. Julia M. Walker. The Elizabeth Icon, 1603-2003. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. xii + 232 pp. ISBN 1403911991 DR MATTHEW WOODCOCK (UNIVERSITY OF EAST ANGLIA) Julia Walker concludes the introduction to her survey of posthumous recastings of Elizabeth I’s image and imagery by asserting that the ‘Elizabeth icon and the place it claims in the common sphere of public memory are, it certainly seems, rich enough to nourish any number of studies’ (p. 5). This appears – at least initially – to be true when considering the number of scholarly works on Elizabeth produced in the last three years to mark the four-hundredth anniversary of her death. The anniversary in 2003 provided the ideal occasion to look back across four centuries and reflect upon the continued popularity of Elizabeth in the public imagination and establish a ‘long view’ of the different ways in which her image has been used and refashioned since 1603. The titles presently under review constitute two examples of works offering critical revaluations of Elizabethan mythography and iconography. Other examples written conterminously with these studies include John Watkins’s Representing Elizabeth in Stuart England (Cambridge University Press, 2002), Michael Dobson and Nicola Watson’s England’s Elizabeth (Oxford University Press, 2002), and the essay collection, Elizabeth I: Always Her Own Free Woman, edited by Carole Levin, Jo Eldridge Carney and Debra Barrett-Graves (Ashgate, 2003). In each of these recent studies it is clear that the focus of much modern scholarship on Elizabeth is directed towards the textual and visual strategies deployed to represent the queen, and their legacy in later literature, portraiture and historical accounts. Indeed it has been observed on several occasions that to study Elizabeth is to study a construct or text: an historical and legal fiction, an entity woven together from records of public speeches, from the figures used to represent her in celebratory poems and pageantry, and from the symbolic and seemingly ageless images of the queen found in royal portraits. Susan Frye goes as far as stating unequivocally that ‘I cannot believe that Elizabeth can be recovered in any absolute sense, even if we finally manage to retrieve more of her voice’.1 The increasing shift away from attempts to recover an essentialist conception of Elizabeth is signalled in the titles of both books reviewed here, and by the critical emphasis now placed upon multiple constructions of the ‘myth’, ‘icon’ and ‘image’ of Elizabeth. Of course the study of Elizabethan myth-making is by no means a new discipline. The so1 Susan Frye, Elizabeth I: The Competition for Representation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 9. called ‘cult’ of Elizabeth has long attracted critical attention and provides a record of the many different representational strategies used in the construction, embellishment and perpetuation of the body politic as it is figured in the queen. But what increasingly distinguishes scholarship on Elizabethan mythography of the 1980s onwards from the earlier generations of research by E. C. Wilson, Frances Yates, and Roy Strong, is a realisation that the queen and her government were not the sole producers of a monolithic, unified iconography for the queen. Images constructed to represent Elizabeth function as sites of potential conflict between different factions and individuals, including the queen herself. As Walker’s earlier collection Dissing Elizabeth (Duke University Press, 1998) revealed, there were also parties both at court and abroad committed to fashioning explicitly negative representations of the queen. It is the continued manipulation of Elizabeth’s myth or iconography that occurs during her own lifetime that forms the natural basis for the successive reconstructions and remythologisations that take place in the four centuries after her death, and that become the focus of the works reviewed here. Susan Doran and Thomas Freeman’s essay collection begins by acknowledging the connection between past and present constructions of Elizabeth, and contemplating briefly the enduring popular familiarity of the queen’s physical image and personality traits that have been shaped into a recognisable set of characteristics for the twentieth- and twenty-first-century public imagination, it is argued, by representations of her in film. The cinematic queen is now a ubiquitous feature of most modern studies on Elizabethan mythography, but here too celluloid myth-makers ‘have merely crystallised and popularised a pre-existing myth about Elizabeth’ (p. 2). Doran and Freeman’s volume focuses upon the Elizabethan genesis of that myth and its Jacobean evolution into what has become its recognised form, and they quickly locate themselves in relation to revisionist traditions of scholarship on Elizabethan myth-making. The book’s first section posits the useful notion of so-called ‘Trojan horses’ of contemporary royal panegyric whereby extended, effulgent praise concealed prescription and censure. Freeman’s opening essay challenges the pervasive assumption that John Foxe’s account of Elizabeth’s captivity during Mary I’s reign was anything more than a straightforward, unambiguous glorification. By carefully tracing the composition of the captivity and accession narrative in the 1563 Acts and Monuments, Freeman reveals how Foxe was clearly shaping his historical materials for a specific purpose. By stressing that God alone was responsible for Elizabeth’s accession, and that the queen’s authority over Church and State was divinely ordained, Foxe, in successive editions of his work, sought to remind her of the obligations God imposed upon her. (The providential nature of Elizabeth’s accession was also a major component of seventeenth-century popular celebrations of the queen, as a wide-ranging essay by Alexandra Walsham later in this collection reveals.) As Foxe constructs it, Elizabeth had an obligation to complete the reformation of the English Church and to further purge lingering remnants of popery, including the wearing of clerical surplices. By the 1576 edition, Foxe includes a range of materials explicitly criticising Elizabeth for failing to enact religious reform. Andrew Hadfield reveals a similar criticism of Elizabeth’s failure to act in accordance with the interests of the more militant Protestant faction that is voiced through the ostensible panegyric structure of Spenser’s Faerie Queene. Hadfield revisits of episodes in the poem where various characters face the difficult challenge of interpreting the subtle distinction between positive and negative female figures (for example, Britomart and Radigund), and in turn as readers we are forced to question which one ‘really’ represents Elizabeth. By the 1596 edition there is increasing difficulty in distinguishing a good queen from bad, and the poem is overtly critical of female sovereignty itself, suggesting that women are incapable of decisive, pragmatic action necessary to rule effectively. Heedful of the obvious question of how Foxe and Spenser got away with such criticism, Freeman and Hadfield demonstrate not only the complexity of collocating censure and praise but also suggest that the queen shrewdly chose to appropriate only the positive aspects of her portrayal in such works and ignore the criticism, displaying Elizabeth’s skill at managing potentially challenging accounts of her reign and policies. The next section of essays examines the emergence of two contrasting images of Elizabeth during James I’s reign. The first is that of the ‘politic, pragmatic ruler, reluctant to fight and hating religious extremism’ (p. 6); the other is that of Elizabeth as a militant Protestant champion. Patrick Collinson’s essay shows how William Camden’s original account of Elizabeth’s reign in his Annales, first published in Latin in 1615, is less responsible for the ‘mythical’ version of Elizabethan history than has previously been thought. Rather, it was the successive English translations of the Annales from 1625 onwards which downplayed the laconic detachment of Camden’s Latin and his sympathetic account of Mary Queen of Scots, stressing instead Elizabeth’s ‘glorious fame’ and fashioning the popularity of her reign as a ‘yardstick’ against which to measure perceived failings of her Stuart successors (p. 85). Both Freeman and Collinson thus offer a muchneeded revaluation of the founding authorities for Elizabethan history and mythography, and their work will be of great importance in guiding subsequent scholars to examine supposed myth-makers Foxe and Camden with a greater sensitivity to oppositional voices than is found in previous studies. Lisa Richardson and Teresa Grant extend the analysis of Jacobean Elizabeth here by examining a number of literary constructions of the queen. Richardson’s innovation is to trace how Fulke Greville and Sir John Hayward each manipulate Sir Philip Sidney’s critique of weak, inconstant monarchs found in Arcadia, that was originally directed towards Elizabeth, in order to construct different models of rule for their dedicatee Prince Henry. Drawing on a nuanced reading of Stuart historiographical methods, Richardson shows how Greville compares Elizabeth to Sidney’s ‘good king’ Euarchus, and how Hayward’s history of Elizabeth’s early reign again depicts the queen in Arcadian terms though stresses the virtue of acting as a pragmatic politician rather than a militant saviour figure. The multiple strands from which the Elizabeth myth was woven are shown again in Grant’s essay on Thomas Heywood’s play If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody. Grant demonstrates how although the first part draws heavily upon Foxe’s glorifying account, the second instalment increasingly aligns the queen’s insistence on her virginity with a greater emphasis on her martial valour, as ‘masculine virtue is reflected by a concomitant arch-feminine chastity’ (p. 135). As this essay indicates gender was a vital factor shaping Elizabethan myth-making. The virgin queen is surely the most well-known example of the many figures used not only to represent the Elizabeth, but to negotiate the relative novelty of female sovereignty, especially from the 1580s when it became clear that Elizabeth would never marry. Doran’s own essay interrogates the virgin queen iconography and re-examines the queen’s visual representations in images commissioned by both Elizabeth and her courtiers. Doran’s rather contentious conclusion is that there appears to be relatively little appropriation of Marian iconography (as argued by Yates, Strong and others), and that in those few portraits where Elizabeth was directly responsible for her own image she is usually represented as a Protestant ruler rather than a virgin queen. Careful contextualisation of a selection of well-known portraits in relation both to their circumstances of production and to the symbolic vocabulary deployed in European visual panegyric reveals Elizabethan portraiture to be far more conventional and derivative than is often realised. Two further Elizabethan legends receive a critical reappraisal within this volume. The first, the enduring idea that Elizabeth vehemently opposed clerical marriage, and that this prejudiced patterns of appointment to the episcopacy, is convincingly challenged in a pair of case studies by Brett Usher. Jason Scott-Warren’s contribution on the mythical legacy of Sir John Harington’s gossipy accounts of Elizabeth’s court urges a rational, contextualised approach to interpreting how the aspiring courtier deploys the queen’s image within his own strategies of self-promotion. Thomas Betteridge’s essay on Elizabeth in films returns to the issue of Elizabethan gender roles, discussing the emphasis repeatedly placed on the relationship between gender and power in onscreen representations of the queen. Concentrating on Fire Over England, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex and Elizabeth, Betteridge reaches the somewhat predictable conclusion that Elizabeth films reflect both the shifting conceptions of gender in society and the imprint this has upon contemporary approaches to Elizabethan mythmaking. This is not the most comprehensive survey of cinematic Elizabeths nor does it begin to engage with discussion of what makes the representation of Elizabeth on film (or television) specifically different from earlier textual and visual depictions; how do cinematic myth-makers exploit their particular medium? Doran and Freeman otherwise assemble a very strong collection of scholarly materials here, and their specific focus upon the Elizabethan and Jacobean stages of the myth-making process ultimately fosters a great coherence to the different approaches to the Elizabeth ‘myth’ undertaken by all of the contributors. The collection demonstrates a commitment to revising the boundaries of our existing understanding of Elizabethan myth-making and scholars of early modern literature and history will welcome the challenges repeatedly made to accepted authorities and conventions, including the perceived orthodoxy of Spenser, Foxe and Camden. Walker’s The Elizabeth Icon offers a far more wide-ranging approach to the different surfaces upon which different ages have projected their (and our) conceptions of the queen. Although as Walker observes, Elizabeth is surely the most recognisable of all English monarchs (barring Elizabeth II), and her image has become an icon for the English nation itself, interpretation of individual, historical reworkings of that icon frequently requires extensive contextualisation and cultural localisation. This is what Walker sets out to provide for a gloriously eclectic range of texts, monuments, images, and objects of curio and kitsch produced from 1603-2003. Walker’s study of multi-generic representations of Elizabeth obviously invites immediate comparison with Dobson and Watson’s 2002 England’s Elizabeth, though the author is keen to highlight that there is little overlap in their choice of analytic set-pieces. Walker’s first chapter looks at the means by which Elizabeth becomes established within Jacobean public memory through the ‘icon’ of her tomb at Westminster Abbey. In particular she examines at some length how James I quickly sought to appropriate that icon through relocating Elizabeth’s body from under the altar of the Henry VII chapel to a new tomb completed in 1606, where she was buried with Mary I. James thus uses Elizabeth to serve his own political agenda, seeking to source his own direct descent from Henry VII and effacing his predecessor’s genealogy. As Walker rightly notes, James’s appropriation of the Elizabeth icon at Westminster was clearly successful, as posterity and the public imagination have all but forgotten Elizabeth’s original resting place. Whilst Doran and Freeman (and Dobson and Watson) examine theatrical versions of the queen on the public stage, Walker’s sections on the seventeenth-century Elizabeth focus on her presence upon the political stage and her appearance within discourses on the marriage of Prince Charles to the Spanish Infanta. Once again Elizabeth is made to embody patriotic militarism and national integrity in the face of a Spanish ‘invasion’. In the midseventeenth century the greatest threat to the royal icon comes from within the nation, though again Walker teases out the doubleness of the Elizabeth image using Milton as a case study. Elizabeth becomes the subject of an interpretative struggle, a signifier capable of representing monarchy and the limitations of the sixteenth-century religious settlement, but also of the constitutional settlement sought by Cromwell. Walker’s methodology in discussing where the Elizabeth icon was used (and not used) during the seventeenth century is to offer a thorough contextualisation and close reading of each of the key texts or sites upon which she focuses. Once she moves towards the eighteenth century however the need for extensive background decreases as Elizabeth’s icon ‘gradually had less to do with specific political events and more to do with popular responses to general social issues, both foreign and domestic’ (p. 89). Walker’s focus here is upon popular histories of Elizabeth, and the utility of the militant Gloriana image in representing Trafalgar and Waterloo. Treatment of the Victorian Elizabeth icon begins by stressing the differences between the two queens’ reigns, observing that Victoria actively rejected any comparison to her unmarried, early modern forbear (as does Elizabeth II). Walker traces instead the emergent mass production of Elizabeth’s image, including its appearance on biscuit tins and tobacco tins. (A later chapter similarly sees Elizabeth appear on tea towels, teapots, and as a rubber bath duck.) The later-nineteenth century also saw attempts, particularly in the visual arts, to conflate the age of Shakespeare with that of Elizabeth through repeated constructions of the queen as the bard’s ultimate audience. Twentieth-century recastings of the Elizabeth icon construct her as a supporter of women’s suffrage, and as a patriotic rallying point during the Dardanelles campaign and in 1940; once again the Tilbury dock rhetoric is marshalled in defence of this island nation. The final chapter considers the second Elizabethan age and returns us to the mass production of the Elizabeth icon, briefly touching upon the cinematic queen, in particular how Shekhar Kapur’s 1998 film Elizabeth stages the birth of the virgin queen figure. One of the weakest points of this book is the concluding coda that attempts to contextualise Elizabeth’s position (at number seven) in the BBC’s 2001 Top Ten Great Britons poll, though merely reveals how little the author knows about later British history or the current popularity in UK television programming for the cultural ‘top tens’ genre. Walker rightly concludes that the existence of Elizabeth ‘gives English-speaking peoples a visual fix on the Renaissance that is unparalleled’ (p. 209), though this point could have equally been made at the end of the preceding chapter, sparing the need for the present conclusion. As testimony to the enduring popularity of Elizabeth outside of academia, Walker’s book appears to be aimed as much at a general readership through its conversational register, and liberal use of personal anecdotes and observations. At times however the pitch was confusing and I wonder how many general readers might be scared off by the largely unnecessary usage of Jürgen Habermas in the section on Elizabeth’s tomb? Walker’s mode of exposition and contextualisation is excellent though too often on reaching the end of a section one found that Dobson and Watson had got there first and drawn similar conclusions in their study, frequently with greater efficiency. Walker’s book is strongest on its seventeenth-century material but on balance Dobson and Watson offer a far more comprehensive survey of the field. Both books reviewed here include examples of negative representations of Elizabeth and overtly critical refashionings of her iconography. But as Doran and Freeman observe it is remarkable how little effect these had upon her myth. Despite Foxe’s and Camden’s critiques of her religion and politics, and early modern Catholic constructions of Elizabeth as a persecutor, it is the image of the queen as a ‘successful, intelligent, calculating, triumphant, but unnaturally masculine ruler who gloried in her unique and somewhat unnatural virginity’ which ultimately won (or is winning?) the competition for representation between the multiple Elizabeths produced since 1603 (p. 15). Although modern scholarly reconstructions of the queen may reveal the complexity of the Elizabeth image, it is the version beloved of National Trust gift-shops and Oscar-winning movies that still wins the popular vote.