molecular_general_theory_genome_organis

advertisement

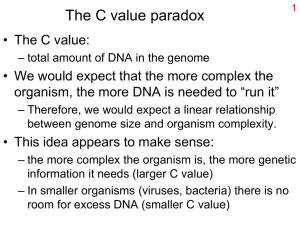

Molecular Biology: General theory Molecular Biology: General Theory Author: Dr Darshana Morar Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution license. GENOME ORGANIZATION All of the genetic information or hereditary material possessed by an organism is known as its genome. Viruses, prokaryotes and eukaryotes contain nucleic acids, with the relative amount of DNA and/or RNA differing depending on the organism. Viruses have the smallest genomes. Prokaryotes have larger genomes than viruses, while eukaryotes have the largest genomes of all. Viruses Viruses contain either DNA or RNA, never both, have no cytoplasm or cell organelles and are obligate intracellular parasites. Viral genomes The nucleic acid may be single-stranded or double-stranded; it may be linear, circular or segmented configuration. Single-stranded virus genomes may be: Positive (+) sense, i.e. of the same polarity (nucleotide sequence) as mRNA Negative (-) sense or Ambisense - a mixture of the two. Prokaryotes There are different groups of prokaryotes, distinguished from one another by characteristic genetic and biochemical features: The bacteria, which include most of the commonly encountered prokaryotes such as the Gramnegatives (e.g. Escherichia coli), the Gram-positives (e.g. Bacillus subtilis), the cyanobacteria (e.g. Anabaena) and many more. The archaea, which are less well-studied, and have mostly been found in extreme environments such as hot springs, brine pools and anaerobic lake bottoms. 1|Page Molecular Biology: General theory Prokaryotic genomes The traditional view has been that an entire prokaryotic genome is contained in a single circular DNA molecule, localized within the nucleoid - the lightly staining region of the otherwise featureless prokaryotic cell. As well as this single ‘chromosome’, prokaryotes may also have additional genes on independent smaller, circular or linear DNA molecules called plasmids. However, this traditional view of the prokaryotic genome has been biased by the extensive research on E. coli, which has been accompanied by the mistaken assumption that E. coli is a typical prokaryote. In fact, prokaryotes display a considerable diversity in genome organization, some having a unipartite genome, like E. coli, but others being more complex. Borrelia burgdorferi B31, for example, has a linear chromosome of 911 kb, accompanied by 17 or 18 linear and circular molecules, which together contribute another 533 kb. Multipartite genomes are now known in many other bacteria and archaea. Eukaryotes Animals, plants, fungi, and protists are eukaryotes, organisms whose cells are organized into complex structures enclosed within membranes. The defining membrane-bound structure which differentiates eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic cells is the nucleus. Eukaryotic genomes All of the eukaryotic nuclear genomes that have been studied are divided into two or more linear DNA molecules, each contained in a different chromosome. All eukaryotes also possess smaller, usually circular, mitochondrial genomes. Plants and other photosynthetic organisms possess a third genome, located in the chloroplasts or plastids. There is a large amount of DNA which does not code for proteins and which varies widely in amount between species. In vertebrates only around 10% of the genome codes for proteins (exons) - much of the remaining 90% has no obvious function and may in fact be simply junk (introns). The differences in genome sizes within a class of organisms are almost entirely due to differences in the amount of this non protein coding DNA. Much of the non protein coding DNA is highly repetitive. The repetitiveness of DNA can be used as a way of classifying the different types of DNA which make up the eukaryotic genome. 2|Page Molecular Biology: General theory Figure 4 Basic structures of eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells 3|Page