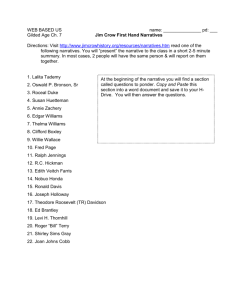

Invisible narratives in the construction

advertisement

Invisible narratives in the construction of past and present The discipline of Ethnology was established at the University of Jyväskylä in 1964, and the study program of Folkloristics in 1968. Since the founding of these disciplines in Finland in the 19th century, some things have changed and some have remained the same. Ethnology and folkloristics are still committed to examining the processes of culture, cultural communication and cultural meaning, but they no longer limit themselves to the study of traditional "survivals" disappearing in face of modernization or 11th-hour attempts to "salvage" and describe disappearing cultural forms. The past is no longer seen as "vanished", but as resurgent, resilient. These days, ethnologists and folklorists understand that the constant emergence of tradition – including beliefs, values and stories – in current contexts is a driving force behind the shaping of human society and culture. The future of ethnological sciences depends on what they contribute, both to thought and to society. The importance of anthropology, ethnology and folklore studies increases as innumerable different ethnic, religious and cultural groups interact and depend on each other now more than ever before. Ethnology has, over the last century, developed precise methodological tools for engaging with an increasingly complex world of cultures, traditions and languages. But we also face new challenges: we must continually remember that culture is not static or monolithic but dynamic and diverse, and we must develop increasingly sensitive methods for studying cultural change and global interactive effects. An underlying premise of ethnology and folklore studies is that the key processes underlying human society and culture are not always the ones we see most clearly. Scholars in the human and social sciences have come to recognize that one of these hidden processes is narrative. Stories are built into our daily lives and our understanding of our world, but often remain invisible to us. While this is not news to folklorists, who have all along studied how cultural life is constructed through narrative passed from person to person by word of mouth, what is new is an interest in how narratives are interwoven with ethics, politics, ideologies, cognition, history and aesthetics, and how hidden narratives have serious implications for how we order and evaluate information about reality and human action. In late modernity, stories and tales have not been marginalized by science and rationality. First, collective myths have not died: people's familiarity with collective stories of the nation's or group's history are highly important in making distinctions between "us" and "them", between "outsiders" and "insiders". Such stories of shared wartime trauma and perseverance, of great leaders and defining moments of triumph, are hardly ever recounted in full: politicians, journalists and social commentators in the media might refer to them only indirectly through passing references, but a primary definition of “what culture is” is that those on "inside" understand these clues and references to a culture’s shared stories, while those on the outside do not. Second, it must be remembered that science is not the opposite of myth: it is itself a grand tale, or set of tales, about progress and discovery. Science has gained the status it enjoys today because it has managed to mythologize itself: it has created its own mythic heroes such as, for instance, Albert Einstein, and it has promoted exciting stories about itself which are today known to nearly everyone: the story of the discovery of DNA, the story of the birth of the human species, the origins of the universe, the destruction of the dinosaurs, and of course THE grand narrative, evolution. Scientists have used the power of stories every time they go to politicians or foundations to ask for funding: Science is compelled to create stories which persuade us to be interested in the knowledge it produces, or which explain how its work can improve the situation of humankind. It has been said that anthropology's study of the "Other" living in exotic cultures has provided an important mirror by which we gaze upon ourselves. What is less often understood is that research into the past provides the same sort of mirror for constructing ourselves as 'modern' in contrast to “traditional” forms of human organization and knowledge. This occurs through hidden stories we tell ourselves about the past, stories that seem to make sense because they support our picture of our 'modern' self and society. Because these stories are rarely explicitly articulated, they are hardly ever the object of intellectual analysis. Assumptions about the past are rarely exposed to the same scrutiny as assumptions about the present, probably because the present contains so many more eyewitnesses who can express their opposing views. Thus even academic scholarship contains generalizations about past eras that we would never make about our own, for instance: (1) that communities in the early modern European countryside were characterized by a greater solidarity and harmony than are urban communities today. Empirical sources from the past few centuries in Europe can shed a great deal of light on this question. For instance, narratives that have come to us from 19th-century rural Finns with little or no education tell a very different story of early modern society. One reason why it has been easy to overlook their stories is that anti-social sentiments were often not expressed openly in older rural communities, but were communicated through covert acts such as secret vandalism, rumor, informal networks and especially witchcraft and sorcery. What no history books mention, and what might have remained unknown if Finland did not contain one of the largest folklore archives in the world, is that just over a century ago the Finnish countryside was in the grip of a witchcraft epidemic as intense as any reported in the 16th or 17th centuries. Rural villages seethed with witches, healers and quarrelsome neighbours who believed they were able to cause each other magical harm. Thousands of first-hand descriptions of magic and sorcery housed in the Finnish Literature Society Folklore Archives provide a window onto a dark and violent side of early modern rural life that has seldom been probed very deeply. Underlying this were the ecological and social conditions of a world very different from our own. Poverty and lack of societal protections meant that in many cases there was a sense of competition, rather than cooperation, among neighbors. Police and criminal detectives were unknown, and the courts could not always compel persons to appear before them. This meant that vandalism, theft, assault, fraud and slander often went unpunished and left victims feeling helpless in the face of their neighbor’s malice and deviousness. For this reason, aggression and revenge were accepted, even admired qualities among many ordinary persons, although the Church preached against them. Persons plotted harm against their “enemies”, and when this harm could not be threatened out loud, it was whispered in rumors and gossip as plans to carry out magical harm. Persons used stories about their own acts of harmful magic to show superior strength and create a reputation for supernatural aggression. People only felt themselves protected and safe if they could create for themselves a reputation as a dangerous person not to be trifled with. (2) because past communities were tied together through ritual, custom, religion and economic dependency, the individual was more tightly bound to society than are modern individuals, who are freer to express their individuality. It must be recalled that the ties that bound early modern communities together were not always ties of shared labor and cooperation. The 19th-century countryside, for instance, was hierarchically stratified even at the level of farmers and laborers, and communal ties were often bonds of economic dependency and unequal work arrangements such as those between master and servant or landowner and tenant farmer. In traditional agrarian Finland, the farm was the only self-sufficient unit of economic production. Anyone who did not own his own land or produce his own food was in some way dependent on the good will of farm masters and farm mistresses. This good will was not always forthcoming, however, and ties of dependency were often interwoven with resentment and distrust. The coming of the modern age did not involve a simple loosening of the individual’s bonds to the collectivity or a freeing of the individual from the shackles of social convention and irrational beliefs. This is a story perpetuated by our modern ideology of individualism. What happened was actually a dramatic transformation in the form taken by the individual’s ties to society. Today, modern individuals are actually bound more tightly to society through the laws of the state, the curricula of educational institutions, and the forces of the market. We are tied to regimens of work, schooling, hygiene, health care and taxes, all of which pervade the everyday lives of modern citizens to an extent unimaginable in previous centuries. It may be argued that individuals are taught a large measure of self-control through schooling and popular literature so that they can then direct themselves in an open, democratic system, but the fact remains that this self-control is only achieved because we surrender a large amount of our autonomy – and several decades of our lifespan – to educational institutions and regimens which, it is hoped, will instill in us modern social conventions to such a degree that the suppression of our desires and impulses becomes automatic and unconscious. (3) And finally, we come to the notion that the traditional past was characterized by a simpler, more holistic world view which has since been fragmented in modern times. 19th-century narratives leave the researcher with the strong impression that the early modern world view was just as complex and fragmented as the late modern world view, if not more so. The view that premodern mentalities were somehow simpler than our own is an artifact of the methods and approaches through which we are often forced to view the past: reductionist lenses which help us to re-create unified and straightforward storylines. But just because we are more familiar with the informational content of our own culture than we are of, say, premodern peasant cultures, does not mean that we can assume that social intercourse in the premodern era carried less or more homogeneous informational content than our own. In fact, our world view could be said to be more unified than that of our predecessors, due to the introduction of mass schooling and the spread of mass media such as newspapers, radio, film and television. Prior to the advent of mass education in the countryside, premodern visions of reality were highly diverse and multiple, and ideas about how to handle disputes, and how to treat others, differed widely. Modern education teaches a common measure of fact, a “universal conceptual currency” for understanding and speaking of human experience. In primary education at least, this conceptual currency has tended to be a realist and materialist view of the universe, but it also contains certain core Western democratic values such as equality, basic human rights, and civic responsibility. In order to understand their implications, the invisible stories woven into our culture must be brought to light. And here is where ethnologists and historians can work together to develop more sensitive theories of how representations of the past are constructed. Without critical reflection on the narratives which represent the very blind spots that remain unexamined and unarticulated in our culture, without understanding how our "invisible stories" shape our visions of our past and thus ourselves, we are less able to navigate the challenges of the future.