Joint AusAID and USAID Review of Support to Hamlin Fistula

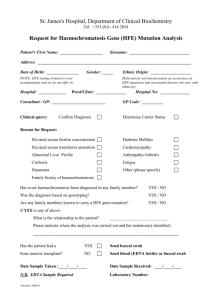

advertisement