Student Teacher Professional Agency in the Practicum

advertisement

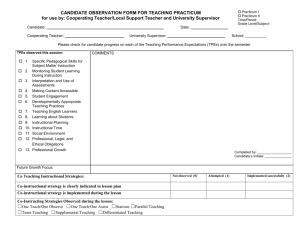

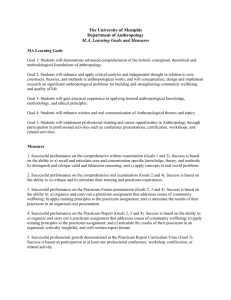

9 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers Student teacher professional agency in the practicum Margaret Turnbull Abstract Teachers are expected to be active professionals in their work. Consequently, the development of professional agency in student teachers is an important dimension in teacher education. This paper reports on a study where the practice of six early childhood student teachers enrolled in a Bachelor of Education (Teaching) was analysed by means of a triadic assessment process to find that only three of the student teachers were deemed to have operated with ‘professional’ agency. Factors, that were perceived to have contributed to or detracted from professional agency, are revealed through an examination of the intersections of practice between the student teachers, associate teachers and visiting lecturers. However, when the practice of the six student teachers was analysed using Giddens’ (1984) concept of agency, each was found to have operated with agency. Stemming from the latter analysis, a model to promote professional agency in student teachers is constructed, and a revised concept of professional agency for student teachers is presented. Teachers are urged to utilise agency in their professional workplace (Edwards, 2001; Edwards & Brunton, 1993; Smyth, 1989, 1991; Smyth & Shacklock, 1998). They are encouraged to be active professionals (Sachs, 2000) and advised to maintain their agency by engaging in reflective practice (Smith, 1999). However, there is a dearth of reference to agency for student teachers. Nevertheless, if teachers are expected to be active agents in their profession then the development of professional agency in student teachers as beginning professionals is essential. Accordingly, this paper, prompted by matrix element 5.11 in the underpinning philosophy of the Auckland College of Education Bachelor of Education (Teaching) stating that graduates will “demonstrate capacity to exercise professional agency with relation to the systems and structures with which they engage” (Auckland College of Education, 1996, p. 19), explores the notion of professional agency for six student teachers in their final practicum of 2000. ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 10 The Participants and Method The participant sample was six Auckland College of Education Bachelor of Education (Teaching) early childhood student teachers of European descent aged from 20 to 42 years; their assigned associate teachers of mixed ethnicity aged from 38 to 55 years; and their visiting lecturers of mixed ethnicity aged from 28 to 67 years. All the respondents were female. By chance, one visiting lecturer was the designated visiting lecturer for three of the student teachers. Each research respondent chose a pseudonym in order to maintain anonymity and confidentiality, and these are used in this study. Working in a qualitative mode of inquiry (Cohen & Manion, 1994), semistructured interviews (Fontana & Frey, 1994) were undertaken with each of the research participants, before and after the student teachers’ final practicum. All interviews, with participants’ permission, were audiotaped and transcribed. Also, the student teachers’ daily reflections on practice were used as documentary evidence of their professional engagement in the practicum. In collaboration with colleagues and students, a working definition of professional agency was articulated after the final practicum of 1999. However, when, by means of a triadic assessment process, that definition was applied to the practice of six student teachers in their final practicum of 2000, only three of these student teachers were deemed to have operated with professional agency. Also, through an examination of the intersections of practice between the student teachers, associate teachers and visiting lecturers, factors perceived to have contributed to or detracted from professional agency were revealed. Seeking greater insight into how the capacity for professional agency might be developed in all of the student teachers, the concept of agency was further explored. Various perspectives on agency (Butler, 1996; Davies, 1991; Gibson, 1984; Jary & Jary, 1991; St Pierre, 2000; Weedon, 1987) were examined and Giddens’ (1984) notion of agency inherent in his theory of structuration was selected as a means of analysing the practice of the student teachers. Structuration theory was chosen as it not only provided a comprehensive perspective of agency, but also offered a view of the practicum as a social system (Turnbull, 2002). Moreover, Giddens’ structuration 11 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers theory was recommended by Shilling (1992) as a useful means of educational analysis. When the practice of the student teachers was analysed using Giddens’ (1984) concept of agency, each was found to have operated with agency. Arising from Giddens’ view on agency a model to promote “professional” agency in student teachers is constructed, and the notion of professional agency is revisited. Teachers and Agency Although there is no mention of the term ‘professional agency’ in relation to teachers in the literature there is reference to the development of agency in teachers. For example, Smyth and Shacklock (1998) discussed the need for human agency in relation to teachers’ struggle to be heard. Edwards and Brunton (1993) believed that teachers should be empowered to engage with the language of education, to dialogue with their peers, and to become fully effective participants in the discourse of education. They emphasised that teachers should become “active agents in the production of a new pedagogic discourse” (p. 156) rather than functioning as consumers of knowledge produced by academics and educational researchers. Tickle (1994) considered that through reflective practice teachers would become agents of change. Likewise, Smith (1999) believed that teachers should celebrate their knowledge base and maintain active agency in their professional work through engaging in reflective practice. Butler (1996) concluded that with regard to the professional development of teachers, “a model of human agency must show how reflection, knowledge, action and the self are related” (p. 269). Embedded in his work on political change Linzey (1998) alleged that teachers must participate in professional discourse about their model of professional practice in order to maintain professional integrity. He emphasised that at all times, personal professional objectives, values, and beliefs must be open to challenge. Sachs (2000) promoted the idea of activist professionalism that requires risk taking and working collectively and strategically with others (Sachs, 2000). In similar vein, Edwards ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 12 (2001) introduced the notion of “deliberative agency” based in a social constructivist framework as a means of enhancing both pedagogy and professionalism. Student Teacher Professional Agency in the Practicum In the absence of a definition of professional agency, the following working definition was articulated as the standard against which the professional agency of student teacher participants in this study would be assessed by means of a triadic viewpoint. Professional agency in the final practicum signifies that the student teacher feels capable of operating competently within the systems and structures of the practicum environment. The student teacher interacts effectively in all facets of professional practice; articulates, theorises and critically reflects upon practice; and exercises moral choice and political capacity in applying pedagogical principles based on a developing but clearly defined professional philosophy. The student teacher operates as a team member, is collaborative, and is free, in the main, from feelings of dominance, dependence, or compliance. The triadic assessment process (Turnbull, 1999), involves the professional judgement of the student teacher, associate teacher and visiting lecturer in determining whether the criteria for assessment have been demonstrated. Pertinent to this study, Table 1 illustrates a summary of the results of the triadic assessment of student teacher professional agency in the practicum. TABLE I. Summary of the triadic assessment of student teacher professional agency Student Teacher Student Teacher Professional Agency Visiting Lecturer Krystal Definitely Elsie Kalara Yes, I did Jessica Student Teacher Professional Agency Associate Teacher Student Teacher Professional Agency Yes Sally I knew it! Ella Yes Esther I do. Definitely Mainly Elsie In a sense, yes Twinkle Not initially Michelle Yes Huia Yes Penny Yes Mary Yes (but) Pat Partially Adrienne Definitely Bella Not in the way I wanted Elsie Yes Caprine Yes 13 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers As illustrated in Table 1 the triadic assessment results indicated that only in the cases of Krystal, Kalara and Michelle was there a clear and consistent opinion that professional agency had been achieved. Mary found that, because she was a student teacher, she held back on expressing her views at times. Also, Pat, her visiting lecturer, considered that Mary, due to gaps in her knowledge and practice, had only partially achieved professional agency. In Jessica’s case, all three assessors had areas of reservations. Bella did not achieve all that she had hoped for in her vision for the practicum, although both her visiting lecturer and associate teacher found her to have achieved the elements in the working definition. The summative triadic assessment indicated that only in the cases of Krystal, Kalara and Michelle was professional agency achieved without doubt in the judgement of the triad of assessors. However, it is not known to what effect the professional judgement of the assessors was swayed by phenomena such as the “Pygmalion effect” (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968). Factors Perceived to have Contributed to or Detracted from Student Teacher Professional Agency An examination of the intersections of practice between the student teachers, visiting lecturers, and associate teachers revealed, from the perspective of those actors, factors that contributed to or detracted from student teacher professional agency. These factors were further grouped into four main categories (see Table 11): The practicum learning environment Student teacher professional knowledge Professional relationships and communication skills Student teacher professional dispositions The Practicum Learning Environment All of the student teachers in this study felt welcomed into the practicum environment, supported by the associate teacher and, in most instances, accepted as a team member. For example Krystal said, “I immediately felt completely accepted and valued as a team member.” The importance of student teacher welcome into the practicum environment and acceptance as a team member is acknowledged in a ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 14 number of studies (Fleet & Clyde, 1993; Hagger, Burn & McIntyre, 1995; Hayes, 1998, 2001). I suggest that a feeling of belonging to the team also contributes to the student teacher’s sense of professional identity in the social system of the practicum. In addition, acceptance as a team member acknowledges the student teacher as an adult learner and allows for self-direction in learning (Jarvis, Holford & Griffin, 1998), self-assessment of practice (Biggs, 1999), and recognition of previous experience and prior learning including the notion of mutual respect (Boud, 1993; Groundwater-Smith, 1999). Pedagogical tact or awareness that learning and teaching are emotional practices is intrinsic to the concept of good teaching (Hargreaves, 1998). Although the data analysis showed evidence of challenge to student teacher practice (Le Cornu, 1999; Martinez, 1998), the predominant culture was one of support indicating the empathetic understanding of the associate teachers. Kalara said, “I appreciated the support and encouragement from Esther. She let me know that I could say anything – be it of a positive or negative nature. She was accepting and challenged me to talk about issues.” However, within the learning environment of some of the centres there were also factors that were perceived to have detracted from student teacher professional agency. In one centre the associate teacher was frequently absent and there appeared to be a lack of a model for planning. These concepts are aligned with the notion of neglectful supervision described by Cameron and Wilson (1993). In other instances detracting factors included the negative attitude of some staff members. Kalara experienced opposition from a staff member in relation to values about practice, “when you have a staff member who is opposing you or what you believe in or want to try, you have to come to a middle ground.” Kalara strategised, “I produced readings from College so that she could think about her practice and I could think about mine.” As disclosed, Michelle coped with internal conflict among the staff in the 15 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers TABLE II. Factors perceived to have contributed to or detracted from student teacher professional agency in the final practicum Categories Factors perceived to have contributed to professional agency Factors perceived to have detracted from professional agency The practicum learning environment Welcome into the centre Positive learning environment Empathetic and supportive associate teacher Effective role-modelling by associate teacher Being accepted and valued as a team member Effective team and collaborative practice Associate teacher absence Lack of planning model in centre Lack of appropriate feedback Negative attitude of staff members Internal staff conflict in centre Dominance of associate teacher Invisible line between being student and teacher Student teacher professional knowledge Feeling and being confident about professional knowledge and ability Effective pedagogical practice A well-defined philosophy of practice Ability to reflect critically on practice Awareness of the socio-political context of the centre Gaps in knowledge about assessment Unclear about some learning outcomes Gaps in practical application of knowledge in some curriculum areas Lack of practice in mat-time Lack of practical teaching resources Lack of a well-defined professional philosophy Effective oral and written communication skills Effectiveness in interpersonal relationships Ability to engage in collaborative practice Ability to interact effectively in a culturally diverse context Establish mutual respect in relationships Self-deprecating body language Lack of social skills in interpersonal relationships Poor written communication Lack of ability in conflict management Lack of negotiation skills Lack of ability to give and receive feedback Positive personal professional dispositions Adverse personal professional dispositions Professional relationships and communication skills Student teacher professional dispositions ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 16 Centre. Bella talked about “the dominance of my associate teacher.” She explained, “I never felt that she was dominating me and wouldn’t like her to think she was. I didn’t feel dependent, maybe compliant is another word.” These examples are indicative of political and emotional tensions to be found in adult relationships (Hargreaves, 1998; Tennant, 1991). They are, nonetheless, difficult for student teachers to contend with during the short-term practicum situation. As in a study reported by Hayes (1998), the student teachers in this study appeared to cope with the negative situations that they encountered. Nevertheless, they found that dealing with such situations detracted from their professional agency. Also, in the instance of the dominance of the associate teacher, it appeared that the student teacher was philosophically and strategically unprepared for this situation. Lack of appropriate feedback was another factor that detracted from student teacher professional agency in this study. Bella said, “I want feedback about my practice. It would also have been nice to talk about my reflections and get some feedback from what I was writing. Having that kind of communication is really valuable.” A responsibility of the associate teacher’s role is to provide on-going feedback to the student teacher with a view to supporting and developing high quality practice. Yet there appeared, in some cases (for example, Jessica, Bella, Mary and Krystal), to be a point beyond which neither the student teacher nor the associate teacher was prepared to explore with regard to some aspects of practice. This phenomenon was consistent with the findings of Wajnryb (1996) who discovered that supervisors used various means to avoid discussing what they thought might be painful issues. On the other hand, a concern for the maintenance of the supervisory relationship may have contributed to the lack of feedback (Mayer & Austin,1999). It is also possible that better communication from the student teachers (Camerson & Wilson, 1993) might have increased the opportunity for professional agency for Jessica, Bella, Mary and Krystal. In some instances, the notion of a positive learning environment was marred by a perceived invisible barrier between being a student teacher and a staff member. The following examples illustrate this perception. Mary disclosed, “If I were an actual 17 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers teacher, I wouldn’t have a dilemma about acting with agency because I would be part of the staff – the tensions arose because I was a student and I didn’t feel I could say anything.” Penny, an associate teacher, revealed, ‘I do look at a student differently from a staff member coming in. When I have a staff member come in, from the first day I have different expectations for them’. It appears that the phenomenon referred to by Mary at one point as an “invisible line” existed in the thoughts of both associate teachers and student teachers. Student Teacher Professional Knowledge After three years of study in the degree programme the student teachers deemed that they were well prepared for the practicum and were confident in their knowledge and abilities. Prior to the practicum, when asked if they considered that they could operate with agency their responses included, “I feel capable of working competently,” “You’ve got these guidelines, rules and principles. You follow them, and the theory will work,” “I am pretty confident.” Post practicum there was evidence from associate teachers that capacity to apply professional knowledge of curriculum and legislative documents, ability to engage in effective assessment and planning to scaffold children’s learning, and aptitude to reflect critically on practice contributed to the professional agency of some of the student teachers. Associate teachers’ perceptions included, “her strength was because of the theory and her use of essential curriculum documents,” “ability to think critically,” “scaffolds children’s learning,” “plans effectively, extends children’s learning, has ability to tap into the wider community.” However, for other student teachers factors that detracted from their professional agency included gaps in professional knowledge and practical application, and lack of a well-defined professional philosophy. Student teachers’ comments included, “my own lack of knowledge in some areas,” “I found myself lacking when it comes to music or art experiences”; visiting lecturers’ comments included, “their theory is great - but they don’t know how to plan,” and associate teachers’ comments included, “more experience needed in working with large groups,” “philosophy of practice should be developed in written form.” It is to be expected that lack of a clear philosophy, and deficit in knowledge and practice would be detrimental to professional practice and to professional agency. ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 18 Professional Relationships and Communication Skills Effective communication skills and the ability to establish appropriate professional relationships are fundamental to teaching, and essential to student teachers’ success during practicum (Le Cornu, 1999; Martinez, 1998). For some student teachers in this study the ability to give and receive respect, engage in collaborative practice, articulate and discuss their philosophy and pedagogical practice, and interact effectively in culturally diverse contexts were aspects of communication that supported professional relationships with the children, staff and parents. However, in other instances, due to staff conflict, the learning environment was already tense and it was more difficult for the student teacher to achieve collaborative practice. This was evident to a greater or lesser extent in the cases of Michelle, Kalara and Mary. Nevertheless, staff dynamics constitute aspects of the socio-political and cultural environment, and interpersonal conflict is a fact of life. Consequently, student teachers must have opportunity to learn how to deal with such issues in their professional practice. Also, each centre should have a process for dealing with interpersonal conflict. It appeared that for some student teachers in this study greater ability in implementing communication skills such as active listening, appropriate body language, dealing with communication blocks, negotiation, and problem solving might have improved their interactions with other adults in the practicum. Student Teacher Professional Dispositions Data analysis revealed that the associate teachers in this research appreciated the positive professional dispositions displayed by the student teachers (Snook, 1992). Antithetically, they were disconcerted by the anti-social dispositions that detracted from the professional stance of some of the student teachers (Katz & McClellan, 1997). Table 111 illustrates the dispositions of student teachers that were perceived to have contributed to or detracted from professional agency in their final practicum. 19 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers TABLE III. Student teacher dispositions perceived to have contributed to or detracted from student teacher professional agency in the final practicum Student teacher dispositions perceived to have Student teacher dispositions perceived to have contributed to professional agency detracted from professional agency Initiative Enthusiasm Professional confidence Disinclination to writing Openheartedness to cultural diversity Lack of personal discipline – staying up Self-direction late socialising and being under par in the Diplomacy and tact morning Collaborative practice Dry humour Intrinsic motivation Self-deprecating body language Professional commitment Off-hand body language Quiet efficiency Lack of initiative Reflectivity Negative attitude that appeared as a lack of Mature approach Openness Sense of responsibility Reliability Sense of inquiry Emotional stability Tendency to think deeply about A tendency to be self-satisfied resulting in a lack of professional inquiry professional commitment professional practice As this study did not set out to discover the dispositions that the student teachers demonstrated it is difficult to ascertain the range of dispositions that were demonstrated during practicum. However, both desirable and undesirable student teacher dispositions were identified in this study. ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 20 An Overview of Giddens’ Perspectives on Agency In exploring how professional agency might be developed in student teachers, Giddens’ concept of agency was applied to each student teacher’s perception of practice and each was found to be an agent who operated with agency. Giddens emphasised that human agents exist in time and space. Pertaining to this perspective, the actors in this study were involved in a seven-week early childhood practicum in 2000. Giddens sees all human beings as knowledgeable agents who have reasons for their activities and who can ‘elaborate discursively upon those reasons’ (1984, p. 3). However, he considers the knowledgeability of human agents to be contingent on three aspects of consciousness. The first, discursive consciousness, is when the individual can articulate the reasons for actions with the degree of rationality dependent on the ability of the actor to articulate her or his knowledgeability. The second, practical consciousness is when the individual can follow the rules of convention but not articulate those rules. It is important to note that practical consciousness can move to discursive consciousness through appropriate socialization and learning experiences. The third aspect of consciousness is when the individual is unaware of motives for action. Giddens pointed out that agents continuously monitor their own actions and those of the social and physical aspects of their working environment. In face-to-face encounters actors observe the tacit rules of behaviour as well as evaluate the competence of the other. Nevertheless, the process of reflexive monitoring of action is also subject to the competence of individuals to rationalise their actions as well as their ability to alter their actions in the light of new discursive knowledge (Giddens, 1984). The Student Teachers as Agents who Acted with Agency When the practice of the student teachers in this study was analysed using Giddens’ notion of agency, each was found to have operated in her discursive consciousness, to have demonstrated capacity to monitor her own actions and those of others, and to have observed tacit rules of behaviour. 21 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers However, the student teachers showed varying degrees of ability to operate in their discursive consciousness. For example Karala articulated her perspective on a debate about mat-time: Then I thought, “if this was a real situation which side would I take”? I figured that less mat-times would be in agreement with my philosophy – give children more time to settle into things, to initiate their own activities, to stay with an activity for as long as they wanted, or to move on if they were no longer interested. Krystal, on the other hand appeared to be less knowledgeable about mat-time than Kalara. It seemed that she relied on her practical consciousness when demonstrating knowledgeability about her practice: I know in this practicum, I didn’t just stay in my comfort zone. I actually – like beforehand, I thought, “I am never going to take a mat-time, I hate it, I hate it.” But I did. I went out there and I guess, I went beyond my boundaries. And definitely my confidence has increased. All of the student teachers showed capacity to monitor their actions. For example, Mary described her interaction with other staff members during a planning meeting that had been called while the children were on holiday: I didn’t want to just pick a strand of Te Whāriki (New Zealand early childhood curriculum) out of mid air and say OK let’s do this one then. And I actually said – “I could pick one up from what was happening before we went on holiday, but I would rather wait until the children come back. We could see where they were at, what was happening for them, and where their interests were, and pick it up from there.” There was evidence of the monitoring of the social and physical environment and evaluation of the competence of others. This is an example from Kalara: ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 22 The teacher wanted more mat-times, while my associate teacher was trying to have less. I was really impressed by the way in which my AT dealt with the situation – like, researching the literature on mat-time to back up her perspective. It was hard dealing with the two sides. I felt it was their issue and they had to deal with it. With regard to the tacit rules of behaviour Jessica articulated her perspectives on the boundaries of professional relationships and personal disclosures: My associate teacher had something going on about her job and she told me what she wanted to tell me. So, like, I still knew what was happening, but not to the depth that the other teachers did. But that was her choice to let me in on as much as she thought. Michelle found herself in an environment where there was dissent among the staff members but politeness in face-to-face encounters. She chose not to get involved in the situation: Face to face with her, they were fine, they were polite. But when she disappeared, there was back-stabbing going on. It was quite a serious problem. But I mean, face-to-face there was no argument. Personally – I tried to stay as far away as possible from the whole thing. Mary realised that she needed to be discreet in interactions with other staff members: I wouldn’t say “oh for goodness sake, that’s a terrible way of doing things.” Bella also chose to don a social mask of politeness: On practicum, I wasn’t truly honest because - I couldn’t be honest – because I didn’t want to devalue other people’s perceptions of what was happening. Even in my reflection – because it was like, if I was truly honest, I would have been critical and I didn’t want to upset anyone. 23 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers In view of the fact that Bella’s associate teacher and visiting lecturer both thought that she had operated with professional agency and had told her so, it is presumed that she was genuine in her conscious desire not to upset anyone. Any unconscious motivation for not doing so remains unknown. The analysis also revealed that each student teacher acted with power in relation to transformative capacity. Krystal took mat-time. Kalara analysed that, congruent with her philosophy of practice, she would vote for less mat-times. Jessica contributed knowledgeably to planning discussions, and tacitly acceded that there were boundaries in professional relationships. Michelle chose to avoid being embroiled in staff conflict. Mary held on to her values about planning for children’s learning, and coached the other staff members into more appropriate practice. Bella, out of respect for the feelings of others, decided not to reveal her true thoughts about what she perceived to be happening in the centre. Thus, all of the student teachers were found to be agents who operated with agency. Although all of the student teachers in this study were depicted as agentic, only three of them demonstrated capacity to operate with “professional” agency. Consequently, It would appear that the extent to which student teachers might operate with professional agency during their final practicum is dependent not only on the depth of their professional knowledge but also their capacity to effectively apply professional knowledge, skills, understandings and dispositions in the practicum context. Conclusions As previously argued if agency is an essential dimension in teachers’ professional practice then the development of professional agency is important for student teachers. Furthermore, arising from the findings of this study it is concluded that the term professional agency in relation to student teachers implies a capacity for effective action that is informed by appropriate professional knowledge. ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 24 This study confirms that a positive and welcoming learning environment within the practicum context contributes to student teacher success during the practicum. It also reveals issues that prevail in some centres, thus highlighting a need for on-going professional development for associate teachers. In addition, this study indicates the necessity for tertiary educators to provide in-depth student teacher preparation for the practicum so that opportunity to operate with professional agency is enhanced. With regard to the student teachers in this study, it appears that if each of them had appropriate opportunity to effectively develop knowledge and practice about assessment, planning, and critical reflection, to develop dispositions necessary to effective professional relationships, to practise communication skills including negotiation and conflict resolution, and to develop a professional philosophy in relation to pedagogical practice with adults as well as with children, they might all have consistently operated with professional agency. However, as Giddens observed, helping an individual to operate in her or his discursive consciousness as opposed to practical consciousness increases the competence of the person, and can be facilitated through appropriate socialisation and learning experiences. Pursuant to Giddens’ theory, I argue that by providing opportunity to develop professional knowledge in an emancipatory-construcivist learning environment where the prevailing pedagogical approach is one that has ‘the capacity to liberate students’ in that it “uncovers and reduces inequality” (Vadeboncoeur, 1997, p. 2), a student teacher’s ability to articulate professional knowledge would be enhanced. It follows that an increase in discursive competence in relation to professional knowledge would contribute to the achievement of professional agency. This concept is exemplified in Figure 1. 25 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers to discursive consciousness requires movement from practical consciousness An increase in student teacher professional agency Opportunity to construct deep understanding of professional knowledge Balance between interpersonal and intrapersonal elements This may be achieved by an emancipatory constructivist learning/teaching environment that provides Critical reflection on practice Figure 1. A means of increasing student teacher professional agency Figure 1 illustrates how student teachers’ professional agency might be increased through appropriate social interaction in an emancipatory-constructive learning / teaching environment where there is provision to scaffold understanding of professional knowledge with significant others on one hand, and opportunity to engage in critical reflection on practice on the other (Vadeboncoeur, 1997). From the outset of their teacher education programme student teachers must be given opportunity to develop a concept of professional agency that is supported by the effective acquisition of appropriate professional knowledge, skills, understandings and dispositions. Consideration of appropriate professional knowledge for teachers will be governed by the values and practice that have currency within national legislation pertaining to teacher education. With this in mind, I suggest that professional agency in the early childhood practicum refers to the capacity of the ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 26 student teacher to effectively apply appropriate professional knowledge, skills, understandings, and dispositions in professional practice contexts. References Auckland College of Education. (1996). Accreditation proposal (Vol. 1). Auckland, NZ: Author. Biggs, J. (1999). Teaching for quality learning at university. Buckingham, UK: SRHE and Open University Press. Boud, D. (1993). Experience as the base for learning. Higher Education Research and Development, 12(1), 33-44. Butler, J. (1996). Professional development: Practice as text, reflection as process, and self as locus. Australian Journal of Education, 40(3), 265-283. Cameron, R., & Wilson, S. (1993). The practicum: Student-teacher perceptions of teacher supervision styles. South Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 21(2), 155-167. Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education (4th ed.). London: Routledge. Davies, B. (1991). The concept of agency: A feminist poststructuralist analysis. Social Analysis, 30, 42-53. Edwards, A. (2001). Researching pedagogy: A sociocultural agenda. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 9(2), 161-186. Edwards, A., & Brunton, D. (1993). Supporting reflection in teachers' learning. In J. Calderhead & P. Gates (Eds.), Conceptualizing reflection in teacher development (pp. 154-166). London: Falmer. Fleet, A., & Clyde, M. (1993). What's in a day: Working in early childhood. NSW, Australia: Social Science Press. Fontana, A., & Frey, J. (1994). Interviewing: The art of science. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 361-376). California: Sage. Gibson, R. (1984). Structuralism and education. London: Hodder and Stoughton. Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. California: University of California Press. Groundwater-Smith, S. (1999). Work matters: The professional learning portfolio. International Journal of Professional Experiences in Professional Education Inc., 3(1), 27-56. Hagger, H., Burn, K., & McIntyre, D. (1995). The school mentor handbook (Paperback ed.). London: Kogan Page. Hargreaves, A. (1998). The emotional practice of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(8), 835-854. Hayes, D. (1998). Walking on eggshells: The significance of socio-cultural factors in the mentoring of primary school students. Mentoring and Tutoring, 6(2), 6776. Hayes, D. (2001). The impact of mentoring and tutoring on student primary teachers' achievements: A case study. Mentoring & Tutoring, 9(1), 5-21. 27 Turnbull September 2004 Issue 14 ACEpapers Jary, D., & Jary, J. (1991). Collins dictionary of sociology. Great Britain: HarperCollins. Jarvis, P., Holford, J., & Griffin, C. (1998). The theory and practice of learning. London: Kogan Page. Katz, L., & McClellan, D. (1997). Fostering children's social competence: The teacher's role. Washington DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. Le Cornu, R. (1999, January). An inclusive practicum curriculum. Paper presented at the Practical Experiences in Professional Education Fourth International Cross-Faculty Conference, Christchurch, NZ. Linzey, T. (1998, July). Life on an icefloe: A metaphor for studying change in the teacher's model of practice. Paper presented at the Second International Conference of the Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices, East Sussex, London. Martinez, K. (1998). Supervision in preservice teacher education: Speaking the unspoken. Leadership in Education, 1(3), 279-296. Mayer, D., & Austin, J. (January, 1999). "It's just what I do": Personal practical theories of supervision in the practicum. Paper presented at the Practical Experiences in Professional Education Fourth International Cross-Faculty Conference, Christchurch, NZ. Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Sachs, J. (2000). The activist professional. Journal of Educational Change, 1, 77-95. Shilling, C. (1992). Structure and agency in the sociology of education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 13(1), 69-87. Smith, D. (1999, February). The what, why, and how of reflective practice in teacher education. A Keynote Address to Education Faculty Staff, Auckland College of Education, Auckland, NZ. Smyth, J. (1989). Developing and sustaining critical reflection in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, XXXX(2), 2-9. Smyth, J. (1991). Teachers as collaborative learners: Challenging dominant forms of supervision. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. Smyth, J., & Shacklock, G. (1998). Re-making teachers: Ideology, policy and practice. London and New York: Routledge. Snook, I. (1992, June). Teacher education: A sympathetic appraisal. A Keynote Address at the Teacher Education Conference: An Investment for New Zealand's Future, Auckland, NZ: Auckland College of Education. St. Pierre, E. (2000). Poststructural feminism in education: An overview. Qualitative Studies in Education, 13(5), 477-515. Tennant, M. (1991). Establishing an 'adult' teaching-learning relationship. Journal of Adult and Community Education, 31(1), 4-9. Tickle, L. (1994). The induction of new teachers: Reflective professional practice. London: Cassell. Turnbull, M. (1999). Assessment in the early childhood practicum. ACE Papers: Working Papers from the Auckland College of Education, (4), 26-39. Turnbull, M. (2002). Student teachers professional agency in the practicum: Myth or possibility? Unpublished Doctor of Philosophy Thesis, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, Western Australia. ACEpapers October 2004 Issue 14 Turnbull 28 Vadeboncoeur, J. (1997). Child development and the purpose of education: A historical context for constructivism in teacher education. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Constructivist teacher education: Building new understandings (pp. 1537). London: The Falmer Press. Wajnryb, R. (1996). The pragmatics of feedback: Supervision as a clash of goals between message and face. In A. Yarrow, J. Millwater, S. De Vries, & D. Creedy (Eds.), Practical Experiences in Professional Education Research Monograph: No. 1. (pp. 135-54). Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology. Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. Oxford: Blackwell. Acknowledgements: I thank Diti Hill for helpful suggestions in regard to this article and also thank Lynne Anderson for her helpful comments.