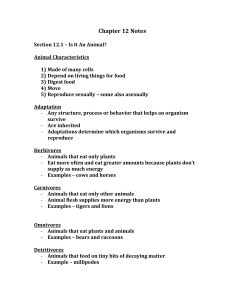

HOTLPage - Hands on the Land

advertisement

(Underlined words link to glossary terms, words that are red link to photos or graphics, words that are red and underlined have a photo and a glossary definition. The other documents on the CD are activities teachers can do with their students. The Leaf Litter Sifter Instructions also contains a classroom activity for doing a soil invertebrate inventory – the PDF’s titled order guide and insect data go along with that. The PDF’s titled spider datasheet and “Key to Common Spiders…” are an extension activity to the Leaf litter activity) Bugs, spiders, creepy-crawlies- these words can make your spine tingle. Slimy earthworms, dirty cockroaches, black widow spiders with deathly bites- all creatures folks often try to avoid. These animals, that can make the hairs on your arms stand up, are actually invaluable members of the earth’s ecosystems. As disturbing as they are to some of us, these creatures are responsible for sustaining most life on this planet, directly or indirectly. They also make up the largest group of living things, more numerous than all other species of plants and animals combined- the invertebrates. What are invertebrates? Invertebrates are, simply enough, animals without backbones. This group is very diverse and includes aquatic animals like jellyfish and sponges as well as terrestrial animals such as all insects, worms, and snails. Scientists continuously attempt to count and describe all of the living species on earth. So far, 1,110,000 arthropod species alone have been described in science. Phylum Arthropoda consists of insects, arachnids, crustaceans, and many other groups. Some scientists believe that if we are able to count all of the arthropods just in the tropical rainforests, the number of species would swell to 10 million! (source: Tree of Life Web Project) How do we know there are so many invertebrates? Great Smoky Mountains National Park is trying to count all of their arthropods along with all other living things in an enormous project called the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory (ATBI). This attempt to find and describe all species in the park has revealed 3901 new species to the park as of fall 2005 (check www.dlia.org for the most recent numbers), some of which are entirely new species to science. Of the 3901 new species discovered in the Park since the start of the ATBI, approximately 80%, are invertebrates. Species new to science found in Great Smoky Mountains National Park include 26 species of beetles, 32 species of flies, 39 species of spiders, and 72 new species of moths and butterflies! Because there are few studies involving this kind of blitz to learn all species, scientists are able to hypothesize that most invertebrate species are still left to be discovered and described. How do we find terrestrial invertebrates? Terrestrial invertebrates are all around us, we just have to think small. Aside from the gnats and no-see-ums that fly around our faces on a hot, humid day or the worms we use to lure fish, there are thousands of creatures working their way through the soil, up the bark of trees, hiding under rocks, or chewing their way into leaves. The tools used by ATBI scientists to find invertebrates are primarily their eyes and a hand lens. To collect invertebrates you can look at or under anything found on the ground or on plants. A fun and easy way to collect is with a leaf litter sifter. This handy tool allows us to shake critters out of the fallen leaf layer on the forest floor into a container that can then be searched. Anything moving can be sucked out of the container using an aspirator or picked out carefully with tweezers and identified or placed into a specimen jar for later identification. A beat sheet is a tool used to catch insects shaken out of bushes or tree branches. A Berlese Funnel is a more technical tool which uses heat from a light source to force insects out of leaf litter and down into a container filled with alcohol or soapy water. Why do we need to look at bugs? The importance of terrestrial invertebrates is immeasurable. Aside from products we can use like bees’ honey and wax, and silk from the silkworm, invertebrates play an imperative role in natural ecosystems. For example, many plants would not be able to grow and reproduce without bees, flies, and other airborne insects. These are the primary carriers of pollen from flower to flower. Relationships between plants and their pollinators can be as specific as the one between the Monarch butterfly and the milkweed plant. Both species are unable to survive without each other, in what is called a symbiotic relationship. Monarch butterfly larva feed on the milkweed plant and then spread it’s pollen to other milkweed plants as an adult. Soil invertebrates help decay materials and create the nutrient-rich humus layer in soil necessary for plant growth. They also serve as a food source for many birds and small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. Either way you look at it, invertebrates play a major role in the cycle of life on this planet. Some species of invertebrates are detrimental to ecosystems. In the Great Smoky Mountains we have lost large numbers of some tree species due to infestation from exotic species. Many of our older Frasier fir trees at high elevations have been destroyed by the Balsam Wooly Adelgid and the young ones continue to be threatened. This non-native insect was brought into the United States on garden stock from Asia. It has no natural predator here and in less than 60 years has drastically altered the appearance and vegetation type of our high elevation environments. The hemlock trees in the park are currently being attacked by the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid. Cooperating research with the University of Tennessee, has found a species of beetle, Pseudoscymnus tsugae (Pt beetle) that feeds solely on the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid. Along with others treatments, we hope to control the adelgid by establishing a self-sustainable beetle population. Monitoring invertebrate populations can tell us the health of an ecosystem. We can determine water quality by looking at the diversity of invertebrates and their larva in aquatic environments (see the Hands on the Land water quality study for more information) . We can also monitor the terrestrial invertebrate population to establish the health of a forest or grassland. This is especially important in areas threatened by air pollution or acid rain, such as Great Smoky Mountains National Park. We are often afraid of those things which we do not understand. By studying the diversity of invertebrate life, we can determine which critters are indicators of healthy or indicators of changing environments. Creepy crawlies aren’t so creepy and crawly anymore, are they? Useful Websites http://www2.lsuagcenter.com/Inst/Research/Departments/arthropodmuseum/index.htm Louisiana State Arthropod Museum, Louisiana State University http://buzz.ifas.ufl.edu/ - Singing Insects of North America http://insected.arizona.edu/info.htm - Arizona State Center for Insect Outreach Education, tons of general insect info http://www.dlia.org/ - Great Smoky Mountains National Park ATBI homepage, contains list of new species, new park records, etc. http://sain.nbii.org/phpqueries/arthropods.php?page=2&scope=myNode – Southern Appalachian Information Node, taxonomic info for arthropods and other links http://www.cdli.ca/CITE/creepy_crawlies.htm - Gander Academy’s Elementary Insect site, info and extra web resources on invertebrates http://www.cdli.ca/CITE/invertebrates.htm - Gander Academy’s Elementary Invertebrate site http://tolweb.org/tree?group=arthropoda – Tree of Life Web Project’s site on invertebrates Spiders: www.arachnology.org – International Society of Arachnology www.stemnet.nf.ca/CITE/spiders.htm - Gander Academy’s Elementary spider info page Berlese Funnel instructions: http://www.cals.ncsu.edu/course/ent591k/berlese.html http://www.albany.edu/natweb/berlese.html GLOSSARY Invertebrates- animals without backbones Aquatic Animals – animals living in the water Terrestrial Animals – animals living on land Arthropod- an invertebrate animal (such as an insect, arachnid, or crustacean) that has a segmented body and jointed appendages, usually with an exoskeleton that molts Insects- a small invertebrate animal, an arthropod, with 3 well-defined body parts (head, thorax, and abdomen), three pairs of legs, and usually one or two pairs of wings Arachnids- terrestrial invertebrates (arthropods like spiders, scorpions, mites, and ticks) with 2 segments to their body and four pairs of legs but no antennae Crustaceans- aquatic arthropods with an exoskeleton or shell, a pair of appendages on each segment, and two pairs of antennae (like lobsters, shrimps, crabs, and barnacles) All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory (ATBI)- a project of Discover Life in America (DLIA), seeks to list and describe the estimated 100,000 species of living organisms in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. For more information click on www.dlia.org Leaf litter sifter- a tool used to collect, or strain, insects shaken out of the forest leaf litter. The students in the photo are using an aspirator to collect very small invertebrates they found using a leaf litter sifter. Aspirator- a tool used to collect insects by sucking them into a vial through a tube. The student in the photo is using an aspirator to collect spiders during a visual search. Beat sheet- a piece of light colored material used to collect insects that have been shaken from brush or low tree branches, a white umbrella or sheet placed under a plant makes a good beat sheet. Berlese funnel- a tool used to collect insects out of leaf litter using the heat from a lamp. Bugs try to move downward away from the heat and end up falling into a collecting jar or bucket. For directions on how to make and use a Berlese funnel, click on http://www.cals.ncsu.edu/course/ent591k/berlese.html http://www.albany.edu/natweb/berlese.html Symbiotic relationship- two dissimilar organisms living together in a mutually beneficial relationship, they each help each other survive Balsam Woolly Adelgid- an insect pest that infests and kills stands of Fraser fir in the spruce-fir zone. Before the arrival of the Balsam Woolly Adelgid, the Fraser fir was the dominant tree at elevations over 6,000 feet in the Southern Appalachians. The adelgid was introduced on trees imported from Europe, and the fir has little natural defense against it. By injecting the tree with toxins through its bark, the adelgid blocks the path of nutrients through the tree. The trees literally starve to death, and thousands of dead snags are all that are left on the highest mountain peaks. Hemlock Woolly Adelgid- a tiny exotic invasive species that gets its name from it’s woolly white protective covering and because its host is the hemlock tree. Adults, as well as the nymphs, suck sap from young twigs on hemlock trees and cause the hemlock needles to dry out and drop, eventually killing the trees. Great Smoky Mountains National Park is currently involved in an aggressive attempt to manage this invasive exotic pest using several methods. For more information, click on www.saveourhemlocks.org Pseudoscymnus tsugae (Pt beetle)- a beetle species known to feed only on the hemlock woolly adelgid and is used as a biological control measure for the hemlock woolly adelgid. For more information, click on www.saveourhemlocks.org/features/feature1.shtml This drawing is of a species of moth that was determined to be new to science. It was discovered in a high elevation forest in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The graphic below links to ATBI in the main text National Park Service Great Smoky Mountains National Park Invertebrates Non-Vascular Plants / Fungi Vascular Plants Vertebrates Known Estimated Unknown Red shows how many of each group researchers estimate are unknown in Great Smokies Mountains National Park. The size of the circle relates to how common the group is in the park as compared to the other groups. The photo below is a millipede that had not been previously seen in the Park so it is considered a new park record.