" Acquiring Vocabulary

advertisement

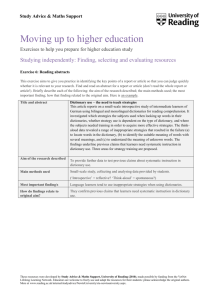

" Acquiring Vocabulary through Self Study " Beyhan KESKİNÖZ Methodology Assignment MSc in Teaching English Languages Studies Unit, Aston University May 1994 CONTENTS PAGE Section 1 Introduction Section 2:1 Neglect of Vocabulary Section 2:2 Reason for the present emphasis on vocabulary Section 3:1 What does it mean to know a word? Section 3:2 Do we forget words? Section 3:3 How do we store and retain vocabulary? Section 4:1 Vocabulary acquisition strategies: some suggested techniques Section 4:2 The place of dictionary Section 5:1 The institution where this study took place Section 5:2 Problem Section 6:1 Method A. Subjects B. Materials C. Instruments D. Procedure Section 6:2 Results Section 7 Conclusion Appendices This study investigated the possibility of helping the students outside class hours to expand and retain vocabulary through self study strategies. Two groups of students ages between 18-20, were selected depending on their mid-term test scores administered in the Spring 1994. A pre-test and post-test, each consisting of 40 questions of vocabulary taught in the Collins Cobuild English Course book2 were prepared and administered by the testing office to determine the degree of success in each group. The analyses of the two measures indicated that the students in GP1 did better than the students in GP2. Pre-test and post-test findings are handled and implication of this are discussed. Section 1 Introduction Communicative value of vocabulary development is not new to anybody in language teaching, and yet the complexity of vocabulary acquisition prevents some people from devoting classroom time on vocabulary. It is possible to save time in language learning. At present, we don't enable our students to be successful learners outside school hours because we don't give them learner training. The classroom time is limited, so what we have to do, as guides, is to help our learners to discover and develop their strategies. I wish to focus on one specific area of learner training: acquiring vocabulary through self study. Section 2:1 Neglect of Vocabulary French (1986p.1-6) mentions two reasons regarding the neglect of vocabulary: 1. The reason why vocabulary was neglected during the period 1940-1970 was that it had been emphasized too much in language classrooms during the years before that time. 2. In the 1950's people began to notice that vocabulary learning in not simply a matter of learning that a certain word in one language means the same as a word in another language. The belief that one could master the language by learning a certain number of words in L2 along with the meanings of those words in L1 was wrong. Knowing a word involves knowing how to use the word syntactically, semantically, and paradigmatically (Carter 1987 p.181). Some people preferred to teach grammar rather than teaching vocabulary which, they thought, would be too time consuming. Section 2:2 Reason for the present emphasis on vocabulary The idea that meaning operates across sentence boundaries is getting popular support among language teachers. Overemphasis on grammar in the language classrooms proved to be unsuccessful as Allen (1983) states: " Through research the scholars are finding that lexical problems frequently interfere with communication; communication breaks down when people do not use the right words ". Allen goes on arguing that in the best classes, neither grammar nor vocabulary is neglected. There is thus no conflict between developing a firm command of grammar and learning the most essential words. Allen (1983) also mentions some questions in his book Techniques in Teaching Vocabulary, OUP (pp 1-6). These questions are important in that they summarise the key problem points in the language teaching field in terms of vocabulary: 1. Which English words do students need most to learn? 2. How can we make those words seem important to students? 3. How can so many needed words be taught during the short time our students have for English? 4. What can we do when a few members of the class already know words that the others need to learn? 5. Why are some words easier than others to learn? 6. Which aids to vocabulary teaching are available? 7. How can we encourage students to take more responsibility for their own vocabulary learning? 8. What are some good ways to find out how much vocabulary the students have actually learned? Some of these questions can be answered by some computerised research because computer corpora allows access to detailed and quantifiable syntactic, semantic and pragmatic information about the behaviour of lexical items (Carter 1987 p.188). The refined information about words made available by computer corpora sheds light on problem areas. Section 3:1 What does it mean to know a word? Wallace (1988 p.27) argues that knowing a word in the target language at the native competence level is the ability to: a) recognize it in its spoken form; b) recall it at will; c) relate it to an appropriate object or concept; d) use it in the appropriate grammatical form; e) in speech, pronounce it in a recognizable way; f) in writing, spell it correctly g) use it with the words it correctly goes with, i.e. in the correct collocation h) use it at the appropriate level of formality; i) be aware of its connotations and associations. To Richards (1974) in Carter & Mc Carthy (1988 p. 44) knowing a word means : 1. Knowing the degree of probability of encountering it and the sorts of words most likely to be found associated with it (frequency and collocability ). 2. Knowing its limitation of use according to function and situation (temporal, social, geographical; field, made, etc.). 3. Knowing its syntactic behaviour (e.g. transivity patterns, cases). 4. Knowing its underlying forms and derivations. 5. Knowing its place in a network of associations with other words in the language. 6. Knowing its semantic value (its composition). 7. Knowing its different meanings (polysemy). Jeremy Harmer (1992 p.158) summarises knowing a word in the following way: Meaning in context Sense relations Metaphor and idiom Collocation Style and register MEANING WORD USE WORDS WORD INFORMATION WORD GRAMMAR Parts of speech Prefixes and suffixes Spelling and pronunciation Nouns: countable and uncountable, etc. Verb complementation, phrasal verbs, etc. Adjectives and adverbs: position, etc. These assumptions made in the light of descriptive linguistics, psycholinguistics and computational linguistics reveal the fact that knowing a word means more than just understanding its meaning. They reveal the complex nature of the vocabulary learning process. Then, the lexical part shouldn't be ignored in language teaching. Carter & McCarthy (1988 p.42) quote Wilkins stating the centrality of meaning: "Without grammar very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can Carter & McCarthy also quote Rivers stating that vocabulary can be presented and explained but ultimately it is the individual who learns: "Students must learn how to learn vocabulary and find their own ways of expanding organizing their word stores." Then individualisation and self-management seem to be a necessary ingredient in language learning. By involving the learner actively in the vocabulary be conveyed." acquisition process, it is possible to increase efficiency. Having learned L1 learners have an experience of language learning, which is a great advantage on the part of the learner. So learners have a lot to contribute from themselves. They must be involved in this process and they must organize their own learning and form their own lexicon. Willis (1990 P.130) also argues that the job of the teacher is to help learners manage their own learning, discover for themselves the best and most effective way for them to learn. To understand an utterance, Widdowson argues, we have to use the linguistic signs as indicators to where meaning is to be found in the context of the immediate situation of utterance, or in the context of our knowledge and experience. In language use, meaning is achieved by indexical and not symbolic means. Giving the following expression: "The liquid passed down the pipe" Widdowson (1986) asks: Why is that we understand the pipe referred to here as a length of tube, rather that a device for smoking tobacco or a Musical Wind instrument? Because the association of liquid and pipe calls up a familiar frame of reference, is indexical of a conventional schema. Wallace (1988 p.64) distinguishes between form and meaning by giving the following example. Jack was sitting on the bank of the river, I am going to the bank to cash a cheque. He calls them different lexical items because they have different meanings. So learners must be aware of such indexical meaning in order to be able to use them. Section 3:2 Do we forget words? Most of the time we meet learners who complain about forgetting the words they have learned. Gairns and Redman (1990) mention two theories of forgetting: 1. We need to practise and revise what we learn otherwise the new input will gradually fade in the memory and ultimately disappear. This is called the decay theory. 2. Cue-dependent forgetting, which asserts that information does in fact persist in the memory but we may be unable to recall it. In other words, the failure is one of retrieval rather than storage. Gairns and Redman (1990) argue that the second theory is supported by a number of experiments. In one of these, subjects were given lists of words to learn and then tested on their powers of recall. Later they were tested again, only this time they were given relevant information to facilitate recall. For example, if a list contained the words "sofa", "armchair" and "wardrobe" the subjects would be given the superordinate "Furniture" as a cue to help them. These experiments showed that recall was considerably strengthened by appropriate retrieval cues, thus suggesting that the information was not permanently lost but only "mislaid". But in both cases one thing is very clear: learners' active involvement is needed to keep the vocabulary active and this seems to be possible with adequate strategies. Carter (1987 P.170) mentions a research reported in Cornu (1979) which indicates that individuals tend to recall words according to the categories or semantic fields in which they are conceptually mapped. Then, if learners study the vocabulary in terms of categories and semantic fields, they will be able to retain more vocabulary for a longer time. Section 3:3 How do we store and retain vocabulary? If one wishes to find an answer to the question " Do we store and retain vocabulary randomly? ", the answer must be "no". Otherwise it would take a long time to recall words as Gairns & Redman (1990 p.87) state: Our "mental lexicon' is highly organized and efficient. Were storage of information haphazard, we would be forced to scan in a random fashion to retrieve words; this simply is not feasible when one considers the speed at which we recognize and recall. Carter & McCarthy (1988) argue that learners make semantic, phonological and associational links between L1 and L2. It seems that learners can store and retain vocabulary more easily if they study items relating by topic, forming pairs etc... That is, they do it in a systematized way. When we think of the number of words in our mental lexicon, the speed is incredible. Gairns and Redman (1990 p.88) cited Freedman and Loftus (1971): the subjects were asked to preform two different types of tasks. l- Name a fruit that begins with a P 2- Name a word beginning with P that is a fruit. The subjects were able to answer the first type of question more quickly than the second. When they are in the fruit category they can remember other fruits more quickly. Semantically related items are stored together in a series of associative networks. Gairns and Redman consider word frequency as another variable which affect storage. Items which occur most frequently are also easily recognized and retrieved. Section 4:1 Vocabulary acquisition strategies: some suggested techniques Ur & Wright (1992 p.4-5) mention a technique which helps vocabulary acquisition and retrieval: brainstorming round a word. One powerful side of this technique is that learners are trying to relate the word semantically. Other variations of the same technique are quite useful in that they help the learner to think hard on collocability of words. Once learners try to use this technique, I believe, they will be actively involved in the learning process, which, in the long run, will help them acquire more vocabulary. Brainstorming round a word: Take a word that you have recently learnt, write all the words associated with it. With a line joining it to the original word in a circle. If the original word was "clothes", for example you might get: DRESS JEANS SOCKS SCARF CLOTHES HAT SKIRT COAT SHIRT Variation 1 : Limit association in some way. For example, write only adjectives that can apply to the central noun so "clothes" might get words like: black, old, smart, warm, beautiful. Variation 2 : A central adjective can be associated with nouns, for example, "warm" could be linked with: day, food, hand, personality. Or a verb can be associated with adverbs, for example, "speak" can lead to: angrily, softly, clearly, convincingly, sadly. Gairns & Redman (1990) suggest another technique: Personal Category Sheets Learners can store new vocabulary as it arises on appropriate category sheets which they can keep on separate pages. These sheets could have headings such as topic areas or situations, these headings being selected by the student himself. As he acquires new vocabulary, he can add to the sheets and cross-reference them where necessary the information given on these sheets (i.e. meaning, perhaps translation, part of speech, and an example) should be comprehensive as suggested below: murder (n) + (v) / ......./ = to kill sb. by plan or intention against the law One big advantage of this technique is that Learners can rearrange these by topic, word-class, etc. Wallace (1988 p.61) mentions three techniques for storing and memorizing vocabulary, which also reflect Individualisation and self-management in language learning. 1. the use of vocabulary cards : The most basic form of vocabulary card has the target word/ phrase on one side and the translation or explanation on the other. (later to be arranged by topic) 2. Meaning bridge - Wallace describes this as on attempt to make some sort of meaning bridge between the target word and its L1 translation. For example Turkish word "dört" is pronounced something like "dirt", five rhymes with hive and four rhymes with door 3. At the elementary level learners can be encouraged to make their own picture dictionaries, using drawings instead of L1 translations. A means of making the learners think actively about what he is trying to remember, instead of the mindless repetition which often passes for vocabulary learning. Rubin & Thompson (1982 p.49) warn that a memory technique that helps one person may not help another. They suggest some options : 1- Put the foreign language words in one column and their translations in another column. Study the list from beginning to end; then study it backwards. 2- Put the words and their definitions on individual cards or slips of paper; then study them in varying order. 3- Study the words and their definitions in isolation; then study them in the context of sentences. 4- Say the words aloud as you study them. 5- Write words over and over again. 6- Tape record the words and their definitions; then listen to the tapes several times. 7- Underline with a colored pencil the words that cause you the most trouble so you can give them extra attention. 8- Group words by subject matter-for example fruits, vegetables, professionsand study them together. 9- Associate words with pictures or similar sounding words in your native language. 10- Associate words with situations- for example, medicines with illnesses. Rubin & Thompson's list offers a variety of options allowing for individual differences. The more systems a learner makes use of and the greater exposure to target items, the easier it will be to retrieve from a variety of sources (Gains & Redman 1990). As guides, our job is to show learners how to be systematic whatever system they adopt. Section 4:2 The place of dictionary Hartman stresses the importance of finding the meaning of a word as an essential ingredient of dictionary use in Bailer (1989 P.130). He lists some of the difficulties which pupils experience at every stage: searching for an appropriate headword, understanding the discourse structure of the entry, identifying the relevant part of the definition, relating the appropriate sense to a given context, and paraphrasing the word by merging it with the source text. This indicates that the learner should be able to overcome such problems if he is to take advantage of dictionary use. Hartman also warns that learners will often fail to find the information they seek if they lack the required constituent skills. Then, students must be taught the proper use of the dictionary. For example, students can be given some exercises which require rearranging words in alphabetical order, finding derived forms under another headword, finding out pronunciation, checking spelling and so on. The dictionary can also give them useful grammatical information. Wallace 1988 diagnoses choosing the meaning appropriate to a given context when several meanings are defined as the major problem in the use of the dictionary. What type of dictionary to use is another point to be considered. At early stages a bilingual dictionary can be used, but it is a fact that monolingual dictionaries encourage students to think in the target language. Harima (1991 p.174) states that there is nothing wrong with bilingual dictionaries except that they do not usually provide sufficient information for the students to be able to use. The entries for the following English words in an English - Turkish bilingual dictionary are all the same: float (v): yüzmek skin (v): yüzmek swim (v): yüzmek There is no doubt, then, learners need more than that. They must be offered a better alternative. Because of the advancements in computer technology, learners are lucky to find a monolingual dictionary as Collins Cobuild dictionary (1990). This dictionary presents a real break away from the traditional ones: It gives examples of real language i.e. how they are used in actual situations with all types of usages. Section 5:1 The institution where this study took place In the School of Foreign Languages, Dokuz Eylül University, İzmir, Turkey, there are about 1800 students who are trained for faculties whose medium of instruction is English, French and/or German. Every year about 1700 students join the preparatory classes to study English. They are given a placement test which also functions as an initial step of the proficiency test. Then they are asked to write a composition of about 250 words. At each step they are graded on a 100 scale. After that, the percentages are taken as follows: Placement test score 70% Composition test score 30% Total 100% If the total score is 70/100 or more, students are eligible to skip the preparatory program. The other students are grouped according to the test scores ranging from beginners to advanced. All groups of the same level are given the same tests prepared by the testing office during the two semesters each of which is 14 weeks. Section 5:2 Problem Fourteen adults chosen randomly have been asked to write down what they have been doing to enrich their vocabulary acquisition . Half the group said that they read the dictionary and wrote down the words if they found the words interesting. Four said they only studied the word in the textbook in lists. One said that he wrote down the sample sentences in the dictionary and studied those sentences. Two said that they wrote words on small pieces of paper and read them from time to time. Discussions with colleagues also revealed that they felt unhappy about the fact that their students were not doing their best to enrich their vocabulary acquisition. In the light of these points, I thought, we could help students do better in terms of vocabulary acquisition by exposing them to some vocabulary acquisition techniques. Section 6:1 Method A. Subjects: In this study two beginners groups were chosen on the basis of the placement test given in the Fall 1993. Now the first term was over and the students had just taken the mid-term test. Depending on the midterm test grades given in the Spring 1994, 7 students, who had the same grades were selected in each group. They were adults, aged between 18-20. From now on these groups will be called GP1 and GP2. The mid-term test scores for GP1 and GP2 are as follows: GRADES Mean GP1 80 80 75 70 65 65 50 69 GP2 85 80 75 70 65 60 50 69 B. Materials : The words to be learned were chosen according to two criteria. First, they had already been chosen on the basis of sound research by Collins and the English Language Research Department at Birmingham University. Willis (1990) argues that the first part of this project had involved the assembly on computer analysis of a 7.3 million word corpus (later extended to over 20 million words) of spoken and written English, which was proposed by John Sinclair. Second, because it was the main course book on the program the students had to acquire the vocabulary given at the end of each unit in Collins Cobuild English Course 2 by Jane & Dave Willis, a lexical-based course book, which came out of the Cobuild Project. C. Instruments: Two 40-item, four choice multiple choice tests, a pre-test and a post-test, were constructed to test retention. Each item consisted of a sentence requiring the use of one of the target words which appeared at the end of each unit in Collins Cobuild English Course 2. The distracters were chosen from among the target vocabulary and were the same part of speech as the correct answer. The pre-test comprised of the target vocabulary from Unit 6 to Unit 10 inclusive, the post-test was constructed from Unit 11 to Unit 15 inclusive. D. Procedure: The two groups studied the above mentioned units with task-based approach as usual. Both groups were taught by the same instructor. When the pre-test was given a week later they had covered the units 6 to 10. GP1 was presented the strategies for vocabulary acquisition, but GP2 wasn't. When the groups were given the post-test a week later they had covered the Units 11 to 15 inclusive. The students were not told the purpose of the tests. They thought they were usual quizzes. The subjects chosen from each group did not know that they were chosen. When the tests were administered in both classes only those subjects' papers were used for comparison. Both groups were given the pre-test after having studied 5 units from Collins Cobuild English Course 2 by Jane & Dave Willis, and we got the following results: GRADES Mean GP1 80 70 63 68 58 75 57 67 GP2 85 70 73 78 55 73 63 71 After that, GP1 was given the strategies mentioned in section 4:1 and a month later the post-test covering the next 5 units from the same book was given to GP1 and GP2. The scores are as follows: GRADES Mean GP1 90 75 73 78 68 85 68 76 GP2 80 70 60 73 60 85 68 70 Section 6:2 Results When we consider the pre-test results in both groups, there is a 4 point difference in the mean performance. GP2 did better in the pre-test. As for the post-test results in both groups the difference in the mean performance is 6 points and this time it was GP1 who did better. The difference in the mean performance in GP1 may seem insignificant, but it is significant when the pre-test and post-test mean performances of GP1 are compared: The difference is 9 points. Another point is that the time during which this experiment was carried out was rather short. It seems that, in the long run, students may be able to get better results. Mc Carthy (1990 p.130) quotes Atkinson (1972) stating that learners who controlled how they learnt words performed 50 per cent better in retention tests than when they had to study random word lists set for them. Section 7 Conclusion Learners learn things better if they are involved in the learning process actively. As Willis (1990) argues: The teacher is not the "knower" but merely a guide and we must put some of the responsibility on the learners shoulders. They should search and find for Themselves and formulate their own rules. So, the best thing to do seems to train learners to take more responsibility for how and what they learn, which, as a result, will pave way for the encouragement of learner autonomy. Learners should be helped to discover what strategy is best for them, and they should be introduced to these strategies as early as possible. It seems to be a good idea to introduce dictionary using skills too. Then, they will have learnt to stand on their own feet. As guides and facilitators, we should also help them realize their success to increase motivation, demonstrating that success breeds success. REFERENCES ALLEN V. F. 1983 Techniques in Teaching Vocabulary, OUP. BAILER R. W. 1989 Dictionaries of English, CUP. CARTER R. 1987 Vocabulary, Allen & Unwin. CARTER R. & MCCARTHY M. GAIRNS R.& REDMAN S. 1988 Vocabulary and Language Teaching, Longman. 1990 Working with Words, Cambridge. HARMER J 1991 The Practice of English Language Teaching, Longman. MC CARTHY M. 1990 Vocabulary, OUP. RICHARDS J.C. 1989 The Context of Language Teaching, CUP RUBIN J.& THOMPSON I. 1982 How to Be a More Successful Language Learner, Heinle & Heinle Publishers Inc. UR P.& WRIGHT A. WALLACE M.J. WIDDOWSON H.G 1992 1988 1986 Five Minute Activities, CUP. Teaching Vocabulary, HEB Explorations is Applied Linguistics 2, OUP WILLIS D. 1990 The Lexical Syllabus, Collins ELT WILLIS J. & WILLIS D. 1988 Collins Cobuild English Course Students book 2, COLLINS.