What is a "Learning Organization"

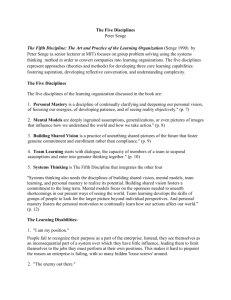

advertisement