North Atlantic and glacial aquifer system in New York

advertisement

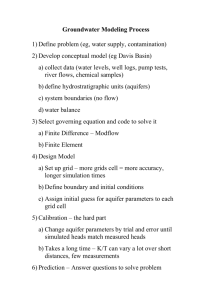

New York, NY (Manhattan Island) Manhattan Borough, New York City, Courtesy Daniel Call, 2010 Introduction According to the New York City Department of City Planning website, Manhattan Island, often known as simply “New York”, has an estimated population of over 1.6 million inhabitants for the year 2008. New York is a worldwide cultural center and a hub for the United States’ economy and financial market. Cultural attractions abound including Broadway, the Empire State building, and Times Square. How does such a large city maintain a consistent water supply to sustain its own population? This presentation hopes to address this question and more. Figure 1, New York Geology (Olcott, 1995) Geologic Background The geology underlying New York City is complex. The Long Island portion of the ‘City’ is composed of the remnants of a series of glacial moraines composed of Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain sediments that were deposited in the Quaternary time period on top of crystalline metamorphic bedrock. Manhattan Island, and the greater portion of the city across the river, has a thin layer of unconsolidated glacial sediments perched on top of Ordovician and Cambrian volcanic rock, as seen from Figure 1. This poses a series of problems in terms of the supply of water to the city. As seen on Figure 2, Long Island is surrounded on 3 sides by sea water with the 4th side being bounded by the Hudson River. Manhattan Island is surrounded by the Hudson River to the west, the Harlem River to the North and the East River to the South and East. Figure 2. New York Water Supply System (New York City DEP, 2007) Hydrologic Background The Hudson River drainage basin and Atlantic Ocean dominate the hydrologic system surrounding New York. Unfortunately, neither source of water is suitable for use. The Atlantic is saline in nature, as befitting an ocean water body, while the Hudson has one of the poorest water qualities in the nation. High concentration levels of metals were detected in the Hudson’s stream bottom sediments, including chromium, lead, mercury, cadmium, copper, nickel and zinc. The Hudson also faces contamination from volatilized organic compounds and derivatives of agricultural pesticides used upstream (Wall, 1997, 1998). Historically speaking, New York’s public water supply began quite simply. In 1677, the first public well was dug, signaling an end to the necessity of having private, shallow wells in the area trying to tap into the shallow glacial till aquifer underlying Manhattan. As the population grew to 22,000 in 1776, the city started constructing artificial reservoirs to enlarge their source for water supply. The continued population growth of the city had a negative effect on well water quality in the aquifer, rendering it unfit for use. After some deliberation, the City voted to commence impounding water from the Croton River and delivering it to the City. Construction of the aqueduct was completed and put into service in 1842. The second phase of expansion of the Croton watershed was completed after being put into service in 1890. In 1905, the New York State Legislature created the Board of Water Supply. This newly founded agency helped to design and construct facilities aimed at developing the Catskill region as a water supply source. Construction was started in 1915 and completed in 1928. Further development efforts generated conflict between the state of New York and New Jersey as the city sought to further augment its supply of water by diverting water from the headwaters of the Delaware River. After the Supreme Court Ruling in favor of New York in May of 1931, construction on the new Delaware Aqueduct was begun in 1937 and completed in 1964. (History of New York City Water Supply, 2010) Efforts to add water derived from the glacial till and Magothy aquifers that lie beneath the surface of Long Island have been tenuous at best. While the region receives significant rainfall, excessive water withdrawal for municipal use has been a considerable problem as salt water has continuously intruded into the aquifer as freshwater has been removed. As such, current efforts to effectively exploit the aquifer are stuck in the stage of trying to understand equilibrium pumping rates to maintain the aquifer against salt water encroachment. (Olcott, 1995) So where does New York get its water if the water bodies around are unusable and the rock layer beneath the city performs poorly as an aquifer? Simple answer is that the City pipes the water in from 3 distinct watersheds: the Catskill, the Delaware and the Croton districts. As figure 2 above shows, the Croton watershed supplies Manhattan and the Bronx when in service, while the Catskill and Delaware network supplies the rest of the metropolitan area during normal operations. According to the New York City 2008 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report, this system supplies over 1 billion gallons of water a day to the city with a total storage capacity of 580 billion gallons. Transmissivity and Storativity values for the glacial till aquifer underlying the city could not be found. All drinking water is derived from surface water flow from the watershed districts and aqueduct systems. The region receives, on average, 40-50 inches of precipitation throughout the year with locally heavier amounts in the Catskill region due to localized lake effect snow events originating from the Great Lakes. This influx of water recharges the reservoirs and aquifers in the region. (USGS New York Precipitation, 2006) Management Practices The city of New York has taken an aggressive stance towards water management policy throughout its history. The city first began building reservoirs to supply the city in the mid 19th century to alleviate problems with contaminated well water in the region. They have continued expanding their water supply maintenance by adding an additional 18 reservoirs, controlling and maintaining 3 lakes and buying up land adjacent to water resources in the area. Interestingly enough, the City was managing water quality and supply before the State had a department designed to address water resource regulation. Recently, the City’s Department of Environmental Protection has partnered with the region’s Soil and Water Conservation Districts to address contamination of local aquifers and to ensure long term maintenance of the water’s high quality. They have also instituted a number of Water Conservation Programs including the Comprehensive Water Reuse Program. This program offers a reduction in water rates for buildings that recycle a large portion of water and reuse it. Water from the reservoirs travel through the more than 6,000 miles of pipes, aqueducts and tunnels that connect the system to the city and does so by using gravity to transport 95% of all water. (New York City Drinking Water Supply, 2008) References Wall, G.R., K. Riva-Murray, and P.J. Phillips, 1998, Water Quality in the Hudson River Basin, New York and Adjacent States, 1992-1995 in U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1165 Olcott, P.G., 1995, Ground Water Atlas of the United States Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont USGS Publication HA 730-M Wall, G.R., and P.J. Phillips, 1997, Pesticides in Surface Waters of the Hudson River Basin – Mohawk River Subbasin in USGS Fact Sheet FS-237-96 accessed online at http://ny.water.usgs.gov/projects/hdsn/fctsht/FS237-96.pdf New York City 2008 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report published by New York City Department of Environmental Protection accessed online at http://www.nyc.gov/html/dep/pdf/wsstate08.pdf New York City Department of City Planning population cite accessed at http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/census/popcur.shtml History of New York City Water Supply (2010) accessed at http://www.nyc.gov/html/dep/html/drinking_water/history.shtml USGS New York Precipitation map (2006) accessed at http://www.nationalatlas.gov/printable/images/pdf/precip/pageprecip_ny3.pdf