BROOKES, W (2005) The Graduate Teacher Programme in England

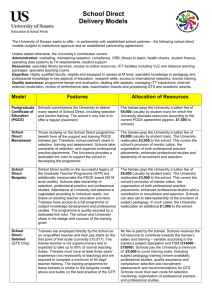

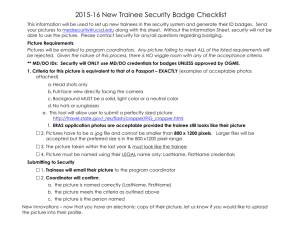

advertisement

Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, University of Glamorgan, 14-17 September 2005 Mary Dunne, School of Education, University of Wolverhampton Beyond Mentoring? School-based tutors’ perceptions of the Graduate Teacher Programme Abstract This paper builds on previous research into how trainees who followed the graduate teacher programme (GTP) route into secondary English viewed their training in relation to the views of those who followed the post-graduate certificate of education (PGCE) route. In line with other studies, a key factor to emerge was the significant role of the school-based tutor (or mentor), particularly for those following the GTP route. The quality of the relationship with the school-based tutor was felt to be of paramount importance in influencing the trainees’ development and the extent to which they regarded their training in a positive light. The paper summarises the findings from the initial study, in particular the issues arising from the perceptions of the GTP respondents, and develops it further to incorporate the views of a small group of school-based tutors (SBTs) about the GTP. This initial group of SBTs was selected following positive evaluation of their practice and of the school training programme by trainees on the programme between 2003 and 2005. Development of the previous work therefore focuses on the school-based tutors’ views of the expectations upon them in training a beginning teacher through the GTP route and how they have developed their training programmes, often largely on their own initiative and at a heavy cost in terms of their own time commitment. Although training through both the GTP and PGCE is done in partnership with the relevant higher educational institution (HEI), since the major part of the responsibility lies with the school-based tutor in the case of a GTP trainee, it can therefore be argued that their role differs significantly from their role in relation to a PGCE trainee. The research begins to explore these additional expectations and responsibilities and begins to identify some of the characteristics of good practice in supporting trainees following an employment-based route. There are close links with the research undertaken by Cartwright (University of Wolverhampton) and Cooper (Open University) on school-based tutor training and accreditation, a regional research project funded by the Teacher Training Agency in 2004-5. This area of research is considered to be essential in view of the significant numbers of teachers being trained by the GTP route and in the climate of current debates about the future of teacher-training and the PGCE, particularly in relation to funding. Introduction Following the Green Paper “Teachers: Meeting the Challenge of Change” (DfEE, 1998), the expansion of the Graduate Teacher Programme (GTP) as an employment-based training route from 420 trainees in 1999-2000 to around 6,000 in 2005, has been at least partly in response to recruitment and retention issues. However, in line with the agenda of the New Right in the nineteen-nineties, the endorsement of employment-based training has also reflected the body of opinion, typified by Chris Woodhead (Woodhead, 1998), that sees it as an antidote to what has been perceived as being “the generalised theories irrelevant to good teaching and removed from everyday life in the classroom” (Lawlor, 1990, p21) underpinning more traditional routes through post-graduate certificate of education (PGCE) courses in higher educational institutes (HEIs). There are significant issues arising from employment-based training, both in terms of the quality and management of initial teacher training offered by the school and the implications for the school-based trainers. The programme has generated mixed reactions. Although there have been some positive profiles in the educational press (Times Educational Supplement, 2004a, 2004b, 2005), concerns have been identified from a range of sources, from the NUT campaign “Now Anyone Can Teach” (Times Educational Supplement, 2003) and postings on the graduate teacher trainee forum on the TES web-site to inspection findings (OFSTED, 2001, 2004) and studies by Foster (2000, 2002), Griffiths (2003), Dunne (2004) and Brookes (2005). The background research (for an unpublished Masters’ dissertation – Dunne, 2004) to the present paper compared newly qualified teachers’ (NQTs) perceptions of their training in secondary English, focusing on two groups of thirteen on the conventional PGCE route and thirteen on the GTP route, within the same HEI. The current research, which is the main focus of this paper, is being developed to explore school-based tutors’ perceptions of the GTP with particular reference to models of good practice that had been identified by the previous research. The research is still in its early stages and the paper is a report of findings so far from preliminary interviews, data from which will be used to inform the design of subsequent questionnaires and interviews to be completed with a larger sample of school-based tutors from a range of providers. The first sample of school-based tutors has therefore been chosen on the basis of trainee feedback from evaluations and questionnaires administered as part of the initial research. The intended focus was on identifying their perceptions of good practice in training beginning teachers through an employment-based route and the impact this has had upon their own workload. There are links between this research and that undertaken by Cartwright and Cooper (2005) as part of a partnership promotion project funded by the teacher training agency (TTA). This project included identification of the training needs of school-based tutors and the training provided by a range of providers in the West Midlands. As part of the research, there were case studies of particular schools focusing on their initial teacher training policies. Findings were used to produce a set of proposed mentoring standards for school-based tutors and professional tutors. The research, however, did not distinguish between GTP and PGCE. The central question for the current paper is whether “mentoring” is an adequate term for the skills and knowledge needed for school-based tutors training GTPs given that they are training beginning teachers within school with minimal input from HEIs and whether, therefore, equating the two routes in this way disguises the real needs of both school-based tutor and trainee on an employment-based route. 2 Phase 1: PGCE versus GTP The original research into the NQTs’ perceptions found that although the best practice for the GTP group mirrored that for PGCE, there were broad areas of difference between the two groups, in addition to much greater variability for the GTP group who perceived their training overall to be less systematic than the rhetoric suggested it would be, compared to the PGCE group who generally felt that they had been well trained. The study, and the findings of those identified above, pointed to the need for continued standardisation within the training and the need to continue to disseminate good practice to all schools involved in school-based training, whichever route is involved. One GTP respondent, who felt that she had received very little guidance or training from the school, summed up her perception of the difference between the two routes as: “We feel we’re alright because we survived; they feel alright because they know what they’re doing.” Most respondents in the GTP group had in practice been filling vacancies even when the school was receiving a salary grant and therefore claiming that they were supernumerary, which is a situation identified by Foster in the early years of the programme (Foster, 2002) and which Brookes describes as “abuses of the spirit if not the letter of GTP” (Brookes, 2005, p45), while Griffiths (2003) refers to conflicting notions of “access or exploitation?”. Research by Bubb et al (2005) into newly qualified teacher induction and what they called “rogue school leaders” identified a typology of “rogue” schools: “a) well-managed school that is ignorant of the regulations and guidance; b) well-managed school that deliberately flouts the regulations and guidance; c) poorly-managed school that is ignorant of the regulations and guidance; d) poorly managed school that deliberately flouts the regulations and guidance” pX. This typology could equally be applied to schools’ position in relation to GTP. If employment-based routes are to reflect the government’s determination that “employmentbased routes into teaching should be recognised as providing high quality preparation for entry into the profession, open to those who may not be able to pursue a more traditional teacher training course.” (DFEE, 1998, p47), then there are key issues to be addressed in relation to the kinds of experiences reflected below: “I didn’t expect to walk into a classroom without even knowing what a lesson plan was and being expected to teach completely on my own all day. I was left alone all day and I think that was wrong. I didn’t even have a register so I didn’t even know who was supposed to be in there. I didn’t know what year they were.” (GTP5) “I think probably…my understanding of the programme was that you only had a small timetable. Some people on the course did just sit in lessons like a PGCE does when they come on a placement …and they observe and do a bit of team-teaching …so I think that idea would have probably worked but the rest of us were just chucked in at the deep end, weren’t we…you’re just filling a gap standing in front of a class aren’t you?” (GTP4) “But I’d never taught before. I’d been in to (a local school) for a week seeing what that was like. And that’s it. And then it was like there you go… off you go… there’s your class and…after a few weeks…we were given some stuff on classroom strategies …handouts… And (mentor) gave us advice like ‘line them up outside’ and that was it basically. Nothing told us about lesson plans or anything like that.” (GTP7) “Because I’d worked at the school for a year beforehand and they’d seen that I’d coped ….I think it was just carry on with the ways things were and I don’t think that 3 was ever ….they thought I could cope and they were all really busy so they never really…they just thought it would continue and I’d do my best and I did.” (GTP1) “The school have been good to me to a certain extent but I also felt that they were getting more out of me than I was getting out of them...I felt like I’ve been seen as an extra body in the classroom, not a trainee.” (GTP9) “At the school I didn’t receive any training as such…I don’t think…nothing formal anyway. I think because I was taken on as a supply teacher, they didn’t see the need to train me. I just carried on from the supply into the teaching…training at the school was pretty much what you picked up as you went along.” (GTP8) These kinds of experiences led to what they described as a “sink or swim” approach, with inadequate support and monitoring, infrequent observation and feedback, little chance to observe others and very little time to “reflect and download”, although they felt that these issues arose because school-based tutors (SBTs) were facing huge odds in terms of time constraints and alternative demands upon them in trying to support them. In most cases, they saw it as “a systems’ failure” (GTP respondent 3) rather than deliberate neglect by SBTs. Trainees in the GTP group felt that they had little time available to develop what Eraut describes as “the disposition to theorize” (Eraut, 1994, p71) that he argues is essential if they are not to “become prisoners of their early school experience, perhaps the competent teachers of today, almost certainly the ossified teachers of tomorrow” (Eraut, 1994, p71). Some saw “theory” purely in terms of a “bag of tricks”, seemingly unable to distinguish between pedagogical issues and subject knowledge, so that their “theoretical” reading was in terms of texts such as “How to Speak Better English – The Idiot’s Guide to Language”! A few articulated theory as the need to reflect on “why you’re doing what you do and why it works…why you need to do it” but even these saw themselves as “lurching from one lesson to another with no time for thought…. like being a hamster on a wheel”. Although there are trainees who have benefited from a much more systematic training programme, most of the GTP trainees in the initial study felt that there was weak assessment of their needs and they had been teaching from the beginning of the year with little beyond a day or two of general induction, often alongside the whole staff. They identified the strengths of their training year in terms of: classroom management (“hands-on experience”) complete involvement in a school over a whole school year the fact that they were seen as teachers ownership of their classroom The best GTP training mirrored PGCE but positive experience was rare in the initial group investigated. GTP respondents reported higher levels of confidence than PGCE respondents in the degree to which they met each standard and in approaching their NQT year although ironically they rated their training less highly and sometimes there was a conflict between their own perceptions of their ability and external assessors’ judgements. OFSTED (2004) pointed out that “fewer GTP trainees teach very good lessons and more teach lessons with some unsatisfactory features” (p2). In GTP respondents’ observations about the training there was a high degree of focus on “self-concerns” (Maynard and Furlong, 1993) with very little focus on the pupils and on teaching and learning issues in contrast to the PGCE group. Success criteria were focused on their own performance and on “cracking” classroom management issues. Their perspective of teaching was much more likely to be contextdependent, focusing on their experience in one school and department. In addition, the following areas were identified: They had good experience of SEN (because of – on average - working in challenging schools and with challenging groups) 4 “Progression” was seen as being increasingly able to slot into how the school operates They felt they were judged against all standards from start They had a narrower experience of ability range because they tended to teach the same classes for the whole year They had reasonably regular meetings with school-based tutors but these were largely concerned with immediate planning and management issues Record of Trainee Assessment (ROTA) tended to be used as summative assessment with a “tick-box” approach Most had very irregular observation – with vague feedback; this was raised as a major issue They had little chance to observe others’ practice They talked about the “disastrous” consequences of early mistakes They were dismissive of “theory” on the whole though some perceived the lack of focus on this as a shortcoming They appeared to be more interested in what to do than why (though not for all) Any “theoretical” reading was focused on practical tips They reported immense pressure from combining teaching and associated work with meeting university requirements They saw assignments as burdensome and “other” HEI training was seen as strength – and was especially welcomed by GTP who saw it as the only “training” they received and who wanted more of this, which is ironic when they chose a school-based route! PGCE In contrast, although they recognised a tendency for school-based tutors to “mollycoddle” them and felt that it was difficult taking over other teachers’ classes since they were not perceived as “real” teachers, the PGCE group felt that they benefited from gradual immersion through an induction period and gradually increasing timetable challenges. They had regular opportunities to observe others’ practice. They were observed regularly with detailed and systematic feedback and felt that they received very strong support from their mentors who used the weekly review meetings to monitor their training needs and progression. They felt that they gained substantial experience of more than one context, which provided them with contrasting models of practice to reflect upon and draw from. The PGCE respondents identified a much wider range of strengths in their training in terms of: developing sound planning skills designed “to meet pupils’ needs” an understanding of the links between management of behaviour and management of pupils’ learning assessment and monitoring practices the focus on pupils as learners and exploration of a range of learning styles their experience of a wide range of ability, rather than being limited to the same group all year their training in the Key Stage Three Strategy which had benefited them during their NQT year the opportunity they had to make mistakes and move on the gradual increase of expectations against the standards and the use of their Record of Professional Development (RPD) as a developmental tool rather than simply being used for summative assessment the theoretical underpinning of their practice and the close links between theory and practice, which were encouraged through the continual emphasis on self-evaluation and reflection This group saw assignments as integral to their developing practice and they reported high levels of very focused support from school-based tutors with regular observations and specific feedback. Weekly review meetings paid close attention to their training needs and to progression issues. 5 Issues arising from quality of mentoring One of the main issues arising from initial teacher training since 1992, when the emphasis shifted towards school-based training, has been the quality of mentoring that trainees on all routes receive in school. This was a significant concern of respondents in the initial study. The OFSTED Inspection of GTP (2004, p3) observed that “half of designated recommending bodies (DRBs) do not implement effective systems to identify and meet trainees’ individual training needs”, particularly in auditing and developing subject knowledge in the secondary phase. Furthermore “much GTP training lacks a clear structure”. One of the most significant findings for employment-based training is the observation that although most school-based tutors have previous experience of initial teacher training (ITT), “four in ten are inadequately prepared to undertake the training and assessment required of them by an employment-based route.” (OFSTED, 2004, p3). Two of the GTP respondents in the study felt that they had received excellent mentoring, one with a school-based tutor who “understood the duality of having to perform a full teaching timetable with the additional requirements of the GTP course” (GTP10) and one who said that the effectiveness came from the fact that “She cared. She wanted me to succeed and she was determined that I would do extremely well…if ever there was part of it I couldn’t do, we would work together” (GTP3). Of the other eight, four had had no consistent mentoring, one because “I started off with a brilliant mentor and six weeks into the course she went off longterm sick…and I knew what I was missing…” (GTP2). One, who felt that she had trained herself, had the headteacher as her school-based tutor which meant that she was extremely busy: “I wouldn’t have said my mentor didn’t care…I was just another job for her but she wanted the status of having said she’d done it. And the time she could really give was very limited. I went to see (mentor) about once every three weeks and I’d go with my ROTA and say, ‘I’ve got a few holes here. What can we do about this?’ and she’d say, ‘Oh read this. Here’s a bit of paper. Photocopy that’ and that was about it.” (GTP1) Another had the assistant headteacher as school-based tutor and although they had fortnightly meetings in the first term of her programme, by the second term he had become acting headteacher and she rarely saw him. Another had three school-based tutors during her programme, changed at short notice – without informing either trainee or school-based tutor – because of internal school politics. Whilst all three were “equally supportive” and the first one very effective, there was very little continuity and two of them were very inexperienced, one of them new to the school herself, so that the trainee felt that “I knew more than they did…we were trying to understand things together.” (GTP9) The others had school-based tutors whom they felt were supportive but who often had very little time to allocate to them, so one respondent reported that “the level of support was second to none” but there was just not enough time allocated for the school-based tutor to observe her and train her systematically. (GTP4) Respondents on both routes showed common agreement about the qualities of effective mentoring, whether they received it or not. It was perceived as being “extremely important for learning” but needed someone who had sufficient time, who “knew what s/he was doing”, who was a good teacher themselves and, crucially, “someone that’s willing to do it would be helpful because at our school they don’t actually ask people (GTP5) There was a recognition from the respondents from both routes that an effective school-based tutor is: 6 “Someone who’s willing to go outside of the mentoring hours as well…one free period really just about covers your ROTA and the report – it doesn’t give you time to sit down and sort out what the hell we’re going to teach year 8 next week.” (GTP5) However, five of the GTP respondents had spent only thirty minutes a week or less with them, which must have had significant impact on their development. Respondents wanted “someone with knowledge of GTP…the willingness to get to know what’s needed of them” (GTP4) since they felt that school-based tutors often did not have a clear sense of the expectations and of how employment-based routes differed from traditional supervised school experience. Half of the GTP group reported that they were observed on average once a fortnight, although for one of these this did not happen in term three and for another, observations from a university tutor replaced school observations rather than supplementing them. The remaining half reported that they were “rarely observed”, by school staff, with one commenting bitterly that “I had about four and they were over a three week period…by the same person…to meet the GTP requirements, to quickly meet the missing bits” (GTP5). Particularly where trainees were filling vacancies, respondents felt that staff did not have available the necessary noncontact time to observe them so observations tended to be spasmodic with no sense of continuity in terms of focus. For some respondents, lesson observations were not felt to be specifically related to review meetings or to completion of the ROTA. These responses were in sharp contrast to the experiences of the PGCE trainees. In relation to observations and feedback, a key issue, in line with the study by Bunton et al (2002), was the importance of the specificity of comments and the perception that a particular feature of good feedback was when strategies were offered. Although both groups had experienced some feedback that was vague and unhelpful, a more serious issue for the GTP group was their feeling that infrequent observations and therefore feedback had hindered their progress. This was a source of considerable anxiety, particularly if the occasional observation that took place was critical: “I think that’s because I haven’t had enough. I think if they were regular, and you’d had enough, you’d see progression in yourself …. but to just get one out of the blue and then it’s got all these criticisms on, I just think what am I doing right …I’m not doing anything right.” (GTP5) However, some of the GTP respondents, particularly the ones who had had less effective support, seemed very defensive about observational feedback, feeling that feedback which they perceived as negative, especially early on, “just made me disaffected…if you’re doing okay and you get people saying ‘I’m just nit-picking,’ all you remember is the nit-picks” (GTP8). It is worth noting here that the study by Bunton et al (2002) found that trainees perceived “points for consideration” as “negative” and this may be a relevant issue for these respondents. Several of them gave anecdotal evidence about lessons where they had been observed to be “satisfactory” when they thought they had been much better than that, for example, one respondent talking about a lesson with a challenging year eleven group said: “They’d actually sat down and we’d got through a poem in the anthology… they knew…they knew about repetition and they knew these things and I just thought it was fantastic but okay I got satisfactory.” (GTP4) Following the initial study into GTPs’ perceptions of their training, and linked with the 2004 OFSTED report on GTP, it was evident that the DRB in which the researcher was a teachereducator working with GTP trainees would need to address the issues raised in order to ensure equality of access to high quality training and support for all trainees. It was clear from the initial findings that many trainees were not receiving even their minimum entitlement and that 7 therefore the DRB needed to establish a protocol of good practice that could be disseminated to schools. It was therefore decided to investigate school-based tutors’ perceptions of the programme with an emphasis on identifying those elements of practice that resulted in a positive experience for trainees on employment-based routes. Phase 2: School-based tutors’ perceptions Therefore, following the findings arising from the initial group of GTP and PGCE respondents, additional data were gathered from evaluations, questionnaires and interviews with a further group of fifteen GTP trainees. Their responses identified schools and schoolbased tutors perceived to be offering high quality training programmes, although there was considerable variation in the characteristics they demonstrated (see appendix 2). To date preliminary semi-structured interviews have been conducted with eleven teachers (representing six schools) involved with training teachers through an employment-based route, all of whom also had wide experience of mentoring trainees on the PGCE. Of these, four are professional tutors responsible for co-ordinating initial teacher training within their schools; the remaining seven are school-based tutors working with secondary English trainees from a range of providers. Interviews were taped, transcribed and analysed according to the headings given. The rest of the paper will present some of the initial findings from these interviews and will consider in more detail (appendix 1) the characteristics of the training programmes offered by one school, where trainees, HEI tutors and external assessors including OFSTED, have rated the provision very highly. Selection of school-based tutors for GTP The seven tutors interviewed had all had experience of mentoring PGCE trainees and five of these were mentoring PGCE trainees at the same time as training a GTP. Four of the seven were also heads of department. Five of the six departments represented also had NQTs at the time of the interview, although one respondent commented that she felt having two NQTs as well as a GTP had been an advantage since it had created a “culture of development and support” within the department. Of the seven tutors interviewed, only one had experienced a formal selection process. Once it was established that a GTP would be joining the department, she had been invited to apply on the basis of her previous work with PGCE trainees and as assistant to the professional tutor for GTP, supporting trainees informally. The remainder described themselves as “self-selected”, with a variety of reasons given for accepting the responsibility: “I was just asked if I would like to” “I really like working with trainees although it is very time-consuming so we are not doing it again” “As I am head of department, I am an obvious choice” “We sort it out between us (head of department and second) because there is no-one else who could do it” Monitoring of school-based-tutors As part of their inspection of DRBs in 2003-04, OFSTED (2004) found that “With few exceptions, DRBs make reliable final assessments for the recommendation of Qualified Teacher Status (QTS). However, a quarter does not monitor trainees’ progress effectively and 8 does not identify early enough those who are making unsatisfactory progress”. How schools and DRBs ensure that SBTs are carrying out their role effectively is therefore a key issue. It needs to be emphasised that these SBTs were selected for interview on the basis of positive experiences reported by their trainees. The systems and procedures described by the sample group of SBTs were not reflected in the experiences of the initial group of trainees interviewed nor in the questionnaire returns from the subsequent cohort. The trainees of the school-based tutors interviewed expressed their awareness that theirs was a minority experience within their cohort. Of particular concern was how school-based tutors are monitored and supported within school. Only two of the SBTs felt that they were formally monitored by senior management with written school policies outlining the process, which was made clear to trainees as well. Regular meetings (at least once a half term in addition to informal discussion) were held between the SBT and the professional tutor, who also had regular meetings with trainees who were encouraged to share any issues arising, what one respondent described as “an open dialogue”. All the SBTs in this group felt that they were informally monitored and that any issues arising for the trainee or for themselves would be dealt with. For three of the respondents there were meetings with other SBTs within the school each halfterm and they felt that this also acted as a check on how they were fulfilling their role as well as allowing them to share their practice. All the respondents said that procedural reminders were issued as appropriate by professional tutors, which helped them with their administration of the programme, although the formality of this varied. The role of professional tutors was felt to be crucial by all the SBTs for the quality of the programme, and in particular having access to a knowledgeable professional tutor who understood the programme and had an overview of the training requirements, especially the generic professional elements, was “essential” in order for the SBT to focus on subject issues. Professional tutors were also seen as an important source of support in helping to carry out observations of trainees as a standardisation measure and where time was an issue. One respondent commented that there was a more formal system for monitoring the induction tutors of NQTs than there was for GTPs. In only one of the schools, were there joint observations of the trainee by the SBT and the professional tutor. Time allocations Time to carry out their training and mentoring role was one of the key issues arising from responses from both the trainees and the SBTs. Only one of the respondents was allocated time in their timetabled contact time and even this had become fortnightly because of temporary staffing shortages. All the respondents in the group interviewed had a timetabled period indicated as one of their non-contact periods but those who were heads of department explained that the amount of non-contact time was the same for all heads of department in their schools regardless of whether they were also mentoring a trainee. All four heads of department had experienced staffing problems over the year and were also therefore having to cover additional lessons. One reported that her mentoring of trainees was done in “snatched time” while another two respondents explained that although theoretically the mentor period was “protected”, they had to meet the same allocation of cover as other staff from their other non-contact periods. Respondents also commented that on a number of occasions they had been called upon to carry out additional tasks in the period supposedly “protected” so that the mentor meeting had to be squeezed in elsewhere, usually at lunchtime or after school. All respondents commented that the time they had actually spent with the trainee was far in excess of the timetabled period, typically at least three hours a week with additional input by other members of staff, with termly reports on the trainee and other administrative tasks associated with the programme being completed at home. All of them commented that training a GTP was much more time-consuming than mentoring a PGCE trainee, especially if 9 they proved to be a weak trainee, and one laughed that “he practically lived with me for the year”. Training as a school-based-tutor The last inspection of DRBs (OFSTED, 2004) found that “Most mentors have previous ITT experience, although four in ten are inadequately prepared to undertake the training and assessment responsibilities required of them by an employment-based route.” The respondents in the sample group had been trained by a range of providers to mentor PGCE trainees. For most of them the training included discussion of observations of trainees teaching (videoed) but nothing on feedback and evaluation. They had all drawn extensively upon their experience with PGCEs in training GTPs but although they had all attended the termly sessions provided by the DRBs to whom their GTPs were attached, these were seen as “briefing sessions” in documentation and procedures rather than detailed guidance about how to train a beginning teacher through an employment-based route when there was much less input from the DRB compared to PGCEs who spent a third of their training year in an HEI. One working with a new provider had no contact with the DRB until the end of the first term and therefore relied on the procedures established the previous year by a colleague working with a trainee from a different DRB. Reflecting research into mentor experiences with different providers for PGCE (Cartwright and Cooper, 2005), all reported significant variations in the expectations, procedures and paperwork of different DRBs. One more experienced school-based tutor, who had worked with a number of GTPs, said that she found the training sessions “too basic” after her first year. None of the respondents felt that they had been provided with a rationale that should underpin training on the employment-based route in contrast to their PGCE experience where trainees had specific focuses for each placement and where there were clear expectations about likely developmental stages. Briefing sessions were pitched as though all GTP trainees were at the same starting point when, in fact, they began their training year with widely differing previous experience, particularly since the reduction in the age restriction since April 2004 means that they can now go onto an employment-based route straight from university. Organisation of the programme As touched upon earlier in the paper, the initial research and subsequent data reveals very significant differences in the way that schools approach the training year. In addition SBTs reported wide differences in the input trainees have from their DRBs, for example with one attending DRB training one day a week while another provided three days each term. Some trainees have an experience that mirrors most PGCE experiences with a general school induction including activities such as pupil trails followed by a number of weeks working within the department alongside the classes of the school-based tutor and other teachers, gradually teaching parts of lessons or small groups before moving on to responsibility for whole groups in key stage 3 with team-teaching in key stage 4. Even within the sample group of school-based tutors selected for their good practice, three out of seven explained that because of staffing shortages rather than because they felt that this was beneficial to the trainee, their GTPs had started almost immediately independently with their own timetabled groups, although closely monitored In articulating what they saw as their organisation of the training programme, all referred to “response to need” and “instinct”. Drawing on their experiences of PGCEs previously, they assessed their trainees in their early interactions in the classroom, and used their observations to draw up subsequent targets. Training episodes were “patterned on occasions of the school year”, examples given being report writing, parents evening, sample SATs marking. Action planning in the form of ongoing targets was informed by lesson observations and by reference to the standards as part of their monitoring of trainees but the research into the trainees’ 10 perceptions indicates that documents such as the ROTA is more commonly used as a summative assessment rather than as a developmental tool. In five out of six of the schools represented, GTP trainees were included in a generic programme of staff training in a range of areas such as behaviour management, child protection, working with gifted and talented pupils and assessment for learning. Only one school (see appendix 1 and appendix 2) had a specific general professional studies programme specifically for GTPs and explicitly linked to their individual training plans. A common feature to emerge from all the research so far is the tendency for schools to include GTPs, regardless of their previous levels of experience, with NQT training or even with whole staff INSET, from which PGCE trainees are excluded. One respondent, working in very challenging circumstances to provide support for a weak trainee, had used Booster money to fund an ex-teacher to work alongside the trainee in the classroom. All commented that their relationship with the trainee was crucial in ensuring that the trainee would ask for help if necessary, although the respondent indicated in the previous paragraph admitted that she had “taken to hiding” from the trainee since he was seeking her out “eight or nine times” a day. Perceived strengths of the route Respondents’ endorsement of the programme seemed, probably inevitably, to be influenced by the calibre of the trainee with whom they had been working so that there was much more enthusiasm from those whose trainees were judged to be “good” or “very good” than there was from those whose trainees were “satisfactory” or “failing”. However, all the respondents felt that the programme could provide a good route for those who prefer to learn “on the job”, with one, who said that her opinion had shifted since working with a GTP trainee, commenting that “you learn so much more doing it…the sooner the trainee is trying it out for themselves, the more they learn.” This was however qualified with “if they have the right support” and all felt that the programme would be much more successful if all trainees were genuinely supernumerary. Interestingly, although most were very complimentary about their trainees’ approach and attitude throughout the training, only one of the trainees represented by the SBTs in the sample had been graded as “very good”; all the rest were “good” or “satisfactory”, which reflects OFSTED findings (OFSTED, 2004) in relation to GTP. All considered it to be a very appropriate route for more mature trainees, widening the opportunity to enter teaching for those who could not undertake a PGCE for financial reasons. However, all expressed reservations about the lowering of the age limit to allow trainees to begin the programme at twenty one and one of the professional tutors interviewed commented that their interview procedure worked hard to “weed out the ‘rush for dosh’ brigade”. All the respondents felt that success on the programme was heavily dependent on the quality of school-based and professional tutors and on the personal characteristics of the trainee, using descriptors such as “resourceful”, “independent”, “extremely hard-working”, “confident”, “willing”. One commented that “the individual is crucial; it was right for her” although another, who had worked with one good trainee and one weak trainee, commented that “some can thrive on that pressure; some collapse.” One considered a strength of the programme to be the opportunity for the trainee to “make mistakes under guidance” although she acknowledged that this depended on the quality of support. This view contrasted with the perceptions of trainees in the initial research when they talked about the “disastrous consequences of early mistakes” when they were working in isolation and ignorance. Reflecting what trainees in the initial study saw as the strengths of 11 the programme, SBTs identified the opportunity to “get stuck in”, arguing that GTP trainees developed good classroom management skills. Several, whose trainees had joined the programme after working as teaching assistants in their schools, felt that GTP trainees developed very effective relationships with pupils compared to PGCEs who only had limited contact. GTP trainees were considered to be more realistic about the school context with greater depth of experience to draw upon. One professional tutor summarised the strengths as: the opportunity for “real life experience” and “unrelenting hands-on” as opposed to the more protected experience of PGCEs; the opportunity to experience “greater breadth and depth”; a greater sense of responsibility and accountability and more realistic relationships with colleagues. Several of the respondents commented that working with GTP trainees is “good for the kids” and “keeps the staff lively”, providing excellent opportunity for mentor development and professional development for the whole staff, particularly where there was a whole-school commitment to initial teacher training. One respondent felt that GTP trainees are much more committed to the school as a whole and present themselves as a professional colleague whereas she described PGCE trainees as being “like pupils from another school”, visiting and wanting to do well but very universityorientated, staying close to the department and to other PGCE trainees. She saw the main strength of the programme as the opportunity to take a trainee who had been working as an unqualified teacher for several years with the development of perceived bad habits and “no real structure” and “completely changing a style of teaching and expectation” in line with what the department regarded as very good practice. “We made her aware of what a professional teacher is – rather than just doing a job.” The schools for whom the programme was primarily a recruitment and retention strategy reported “very high” retention rates with GTP trainees “usually” being promoted to positions of responsibility within their first two or three years of teaching. One commented that having GTP trainees in the department allowed a great deal of flexibility, particularly once they were established, and allowed the head of department time for observation of colleagues and teamteaching. Issues arising As indicated previously, all respondents felt that the programme could only be really effective if trainees were supernumerary, even when their own were not. They felt that trainees needed a substantial induction period to carry out preparatory reading and school- and departmentbased tasks and observations. They needed a period of time working alongside their schoolbased tutor and other teachers, working with individuals and small groups and then gradually assuming responsibility for part and whole lessons and gradually extending their experience over the various key stages. They needed to engage in joint planning and assessment exercises before being responsible for this individually. Echoing Eraut’s concerns quoted earlier, two respondents expressed concern about the long term effects of the programme on the quality of teachers produced when the context of their training did not reflect the better practice, for example those trainees filling vacancies in challenging circumstances with poor support systems and inadequate monitoring. One of these who felt that the success of the programme was very dependent on the quality of the applicant described the programme in her experience as being about “who you had to have” because of staffing shortages and, in her case, senior management willingness to have a body in front of a class almost regardless of suitability: “everyone is short-changed. It’s a cheap, easy answer.” These respondents felt that trainees needed “more time to study pedagogy” and felt that, from their own experience, there were far more issues over subject knowledge than there were for PGCEs. In particular, grammatical and linguistic knowledge, identified as an issue for many trainees of all routes, was more problematic for GTPs because there was much less time available to address it, especially if the trainee was filling a vacancy. 12 Time to train a graduate teacher effectively was felt by all to be the major issue and this included time: to establish a rationale for the training; to set up an appropriate training plan; to carry out training events with the trainee; to observe them in the classroom; to feed back effectively; to complete the accompanying paperwork; to liaise with colleagues; to undertake more extensive training for themselves in supporting them in their role. A particular issue, even for those whose trainees received regular observation and feedback, was the quality of feedback received since, as one respondent commented “when time is short, I resort to saying ‘I saw this….; you need to…’ rather than the reflective dialogue I would consider to be good practice.” Respondents working with the GTP for the first time felt that they “had been making it up as they went along” with no systematic overview of what was required in training a beginning teacher beyond the procedural and administrative details. Although they were all experienced mentors, they felt that the challenges of training a GTP trainee went far beyond the issues associated with the PGCE route and they felt that this was not recognised at senior management level. They expressed uncertainty about the pace of progression that could be expected and about what could realistically be expected of a trainee at what stage, wanting much more guidance about how to manage and support a problematic trainee. Access to supporting resources for both the school-based tutor and the trainee was another issue since PGCE trainees were considered to have much easier access to HEI resources than GTP trainees. One school had established a library of resources, including web-based materials, specifically for GTP trainees and a second school was in the process of doing so. One professional tutor, who worked with GTP trainees in a range of schools, felt that there were widespread abuses of the system, and of the funding and would like to see “spot checks by the TTA”. Conclusions In conclusion, from this very small initial study of perceived good practice in managing the GTP, a number of suggested key characteristics emerge: Selection of trainees suitable for an employment-based route should be rigorous and they should be able to offer significant previous experience in schools successful programmes need a committed professional tutor with a good knowledge of the implications of the programme they need to be supported by, and support, school-based tutors who are willing to undertake the role and who are committed to providing high quality training for beginning teachers all those involved in delivering the programme need adequate time to carry out the role effectively and there needs to be recognition that this will involve substantially more time than supporting a PGCE trainee. Time to fulfil the role should ideally be included as part of their contact time in recognition of the level of responsibility involved school-based tutors need to be carefully selected and monitored closely a good training programme will arise from a whole-school culture of commitment to initial teacher training and to improving the quality of teaching and learning within the school trainees need to be supernumerary the training will be enhanced if the trainee’s department is committed to selfevaluation and review 13 there should be a rationale, agreed at whole school level, underpinning the training programme and trainees’ progress should be monitored systematically with a clearly structured programme of observations and feedback school-based tutors should receive training in observation and feedback skills as well as in mentoring skills and procedural issues unless the trainee has considerable experience of teaching whole classes, then assuming responsibility for whole groups should be staged gradually, after an induction and preparation period 14 References BROOKES, W (2005) The Graduate Teacher Programme in England: mentor training, quality assurance and the findings of inspection. Journal of In-Service Education, Vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 43-61 BUBB, S, EARLEY, P and TOTTERDELL M. (2005) Accountability and responsibility: ‘rogue’ school leaders and the induction of new teachers in England. Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 255-272 BUNTON, D., STIMPSON, P., and LOPEZ-REAL, F. (2002) University Tutors’ Practicum Observation Notes: format and content. Mentoring & Tutoring, Vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 233-252 CARTWRIGHT, L and COOPER, V. (2005) Mentoring Standards for school-based tutors in initial teacher training and induction tutors for newly qualified teachers. West Midlands Partnership Promotion Project 2004-2005 funded by the Teacher Training Agency. DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT (1998) Teachers: Meeting the Challenge of Change. London: TSO DUNNE, M (2004) Anyone can teach: a case study of newly qualified teachers’ perceptions of their training following the PGCE route compared to the GTP route. Unpublished dissertation towards Masters’ degree: University of Wolverhampton ERAUT, M. (1994) Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. London: Falmer Press FOSTER, R. (2000) The Graduate Teacher Programme: just the job? Journal of In-Service Education, Vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 297-309 FOSTER, R. (2002) ‘The Carrot at the End of the Tunnel’: appointment and retention rates of teachers trained on the graduate teacher programme and a full-time PGCE compared. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Educational Research Association, University of Exeter, 12-14 September. FURLONG, J. and MAYNARD, T. (1995) Mentoring Student Teachers: The Growth of Professional Knowledge. London: Routledge. GRIFFITHS, V (2003) Access or Exploitation? A case Study of an employment-based route into teaching. Paper presented at ‘Teachers as Leaders: Teacher Education for a Global Profession’, ICET/ATEA conference, Melbourne, Australia, July 20th-25th LAWLOR, S (1990) Teachers Mistaught: Training in theories or education in subjects? London: Centre for Policy Studies MAYNARD, T. and FURLONG, J. (1993) Learning to teach and models of mentoring. London: Kogan Page OFSTED, (2001) The Graduate Teacher Programme. London: OFSTED OFSTED, (2004) An Employment-Based Route into Teaching: An Overview of the First Year of the Inspection of Designated Recommending Bodies for the Graduate Teacher Programme 2003/4. London: OFSTED TIMES EDUCATIONAL SUPPLEMENT. NUT Advertisement. 12th December 2003, p14 TIMES EDUCATIONAL SUPPLEMENT (2004a). Where do I sign, Mr Robinson? (Accessed via http://www.tes.co.uk/search/story/?storyid=391311 on 12th May 2005) TIMES EDUCATIONAL SUPPLEMENT (2004b). Class in the craftroom. (Accessed via http://www.tes.co.uk/search/story/?storyid=2052950 on 12th May 2005) TIMES EDUCATIONAL SUPPLEMENT (2005). Straight in at the deep end. (Accessed via http://www.tes.co.uk/search/story/?storyid=2069096 on 12th May 2005) WOODHEAD, C. (1998) Guardian/Institute of Education debate. The Guardian Education, 15th December, p17 15 Appendix 1 School A case study: exemplifying good practice School A is an inner city, voluntary aided Catholic school with 1050 on role. It is a mixed 1118 comprehensive, with a diverse multi-cultural community. In achieving 87 % A*-C grades at GCSE in 2004, it is a category A school for value-added compared to similar schools. It offers a wide range of extra-curricular activities to pupils and facilitates international connections and visits. It is a Sports College and has training school status as well as being a partnership promotion and Leading Edge school working closely with local primary and secondary schools, particularly through its eight Advanced skills teachers (ASTs). The school has a very strong commitment to initial teacher training, working with nine providers for a range of routes. During 2004-5, the school was host to sixty eight trainees, including those on pre-training “taster” sessions, the student associate scheme, GTP and traditional and flexible PGCE. GTP trainees have been trained in the school for the last four years. The training school manager, assisted by a deputy, liaises with all the providers, meeting regularly with tutors from the providers and ensuring that all trainees are well supported by their departments. She provides INSET both within the school and externally to develop knowledge and skills in the school’s own trainees and those in local schools. As an AST in English, she also works both internally and on outreach to schools city wide to support colleagues either on subject specific issues or CPD issues generically. As professional tutor, she is responsible for the smooth running of trainee induction, including a tour of the school, familiarisation with school policies and documentation, discussion and guidance on generic issues such as classroom management and lesson planning. NQTs have twilight training every Monday to which GTPs are invited, together with trainees from cluster schools. All trainees, both PGCE and GTP, are expected to use non-contact time to observe experienced colleagues as often as possible and work closely with their mentors. There is a formal programme of observation of trainees carried out by the professional tutor and by designated senior members of staff, including ASTs. On one morning a week GTP trainees follow a professional studies programme in conjunction with GTP trainees from cluster schools. School closes early for pupils on Friday afternoons to allow departmental training in which GTPs are fully involved. GTP training is a major focus for the school, both as a recruitment strategy and because of the school’s belief that it provides high quality training for beginning teachers. Because trainees are supernumerary, not all of them can be employed by the school at the end of their training year but they are assisted in applying for posts for their NQT year. There is a great deal of support for the programme from the school leadership group and in terms of funding. The school is assisted in this area by additional funding (worth £50,000 in 2004-05) because of its training school status. This allows the school to allocate the professional tutor two and a half days a week to be spent on initial teacher training. Applications for GTP places arrive in large numbers each year and these are carefully scrutinised by the professional tutor, the Headteacher, the head of department and sometimes the senior management team member in charge of personnel before a visit to school is offered. The school is inundated with applications from prospective trainees. The school demonstrates a commitment to ensuring that all trainees, regardless of route, experience the same high quality training. The training programme is designed to provide trainees with the background to current thinking on such topics as lesson design whilst equipping them with practical ideas and strategies to use in the classroom often incorporating the latest technologies such as interactive whiteboards and voting pads. 16 School-based tutors for GTP undergo a formal selection process, with suitable applicants who have had previous experience of mentoring PGCE trainees, invited to apply by the professional tutor according to her assessment through joint observations and review meetings of their personal qualities and the quality of their interaction with trainees. There is no programme of school-based training in mentoring skills but there is a strong support network for mentors and regular meetings of school-based tutors where there is sharing of issues and procedures. In addition, all school-based tutors attend the training provided by the HEIs and designated recommending bodies (DRBs), although the quality of this was perceived to be varied. School-based tutors are monitored closely by the professional tutor by constant discussion about trainee progress and by constant dialogue with trainees. Although this happens rarely, if a school-based tutor’s approach still proves to be detrimental to the progress and well-being of the trainee after support has been put in place, then they are formally deselected in a meeting with a member of the senior management team. One example cited was a school-based tutor who “treated the trainee like a leper” and was felt to be cold and overly critical, “making mountains out of molehills”. In addition to their school-based tutors, trainees are allocated a “buddy” within the department, a main scale teacher who is matched by age as far as possible. Trainees have been provided with a workroom, equipped with IT facilities and access to relevant training resources including professional texts. The school is in the process of establishing an intranet for training purposes where trainees will be able to access materials including video clips of lessons to discuss and evaluate. An administrative assistant is employed for two and a half days a week specifically to support the professional tutor with initial teacher training. The role of the professional tutor in this programme is crucial in constructing the programme and delivering the generic aspects so that departments are free to focus on subject-specific issues. She pays a key role in monitoring the progress of the trainees and in ensuring quality of experience, intervening if necessary when she feels that they are being used as a “dogsbody” or being imposed upon. She has a keen eye to their entitlement and to ensuring that this is delivered. 17 Appendix 2: Features of perceived good practice demonstrated by schools in study Generic training – GTP specific Generic training to include GTPs, NQTs and new staff Generic training as part of whole staff INSET Formal selection procedures for school-based tutors (SBT) Formal monitoring of SBTs by professional tutor and/or school leadership group Informal monitoring of SBTs by professional tutor and/or school leadership group Weekly meeting timetabled as part of SBT’s contact time Weekly meeting timetabled as part of SBT’s non-contact time Timetabled schedule for observation of trainee Trainee supernumerary Formal programme of support meetings for all SBTs in school Library of resources available for trainees Separate workroom with IT facilities for trainees Graduated programme with increasing timetable Formal training programme for GTP shared at whole-school level Initial (planned) induction period before beginning programme for trainees new to school School A Yes Yes School B No Yes School C No Yes School D No Yes School E School F No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Usually No No No Some procedur al No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No Yes No Yes No No No No Yes No No but planned No No No No Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes No – but invited to observe No – but invited to observe No No No 18