Understanding Poetry

Understanding Poetry (Verse)

Because of the varied nature of poetry and the literary features used within a poem, it is important to focus on two main things:

Content – WHAT is being said?

Style – HOW is it being said?

Waitaminute! These are the same two questions we should ALWAYS focus on (or ‘on which we should always focus’).

Remember: there is very little value in simply identifying the features unless you explain the effects they create within the text and on the reader.

Classes of poetry

lyric – generally spoken by a single voice expressing ideas and emotions

narrative – includes a narrator and a story; epic poetry was narrative; lacking “emotion”

dramatic – a clearly invented speaker voices the poet’s ideas and sentiments; Shakespeare wrote dramatic poetry

Conventions of meaning in poetry

speaker/voice – frames the words

Tone, mood, and atmosphere

The overall effect that a poem creates in the mind of the reader is very closely linked to the mood and tone that it evokes.

tone – created by the “voice” of a poem; author’s (or speaker’s) attitude towards subject and/or audience

mood – although closely linked to tone, mood refers to the atmosphere that the poem creates

Very often tone and mood are closely linked and a certain tone produces a certain mood. For example, if a poet uses a lively, humorous tone it is far more likely to produce a light atmosphere than a melancholy one.

Diction

The choice of words has an essential effect on how tone is created.

literal/denotative meaning

connotation – meanings the word has acquired or been assigned by the poet

formal or informal register

archaism – older word not used today

neologism – invented or made up word

concrete or abstract nouns

Imagery

Imagery adds layers of meaning to a poem beyond the literal sense of the words on the page. Images can be created in various ways and language used in this way is sometime called “figurative language.”

literal image (imagery) – the image is created through descriptions

non-literal image (figurative language) – the image is created through comparisons; how to represent one thing by means of another o simile o o o metaphor personification

analogy – comparison o o

symbolism – the symbolic image (color white) as representative of something else (peace)

conceit – a type of metaphor where the poet takes very different things and combines them in a startling way o hyperbole

o o understatement

metonymy – close association of one word to another so that one may stand in for the other o synecdoche – part represents whole

kenning – word or phrase, used by Old English poets, that were made up to identify a particular object or thing without naming it directly noun ocean ship a lord kenning swan’s road; foaming field; realm of monsters sea goer; sea wood dispenser of rings; treasure giver the sun candle of the world

Aural Imagery

alliteration – “Full fathom five thy father lies, / Of his bones are coral made.” (repetition of the “f” sound creates a

sense of solemnity and gives incantatory feel to the line)

assonance – “Summer grows old, cold-blooded mother” (creates impression of lethargy and lack of life as summer passes and winter approaches)

onomatopoeia – “The ice was all around; / It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,” (suggest sounds of icebergs)

Again, remember: there is very little value in simply identifying the features unless you explain the effects they create within the text and on the reader.

Form and structure

The way that the language of the poem is laid out will have been carefully chosen by the poet to enhance or reflect the meaning of the poem. Form can refer to the way that the poem is written on the page, or the way that the lines are organized or grouped.

fixed form: o stichic poetry – lines follow on from each other continuously without breaks

o strophic poetry – the lines are arranged in groups, which are sometimes incorrectly called "verses"

(correct term is stanza); sonnet, ballad, ode, etc.

free verse/open form – no constraints of form, structure, rhyme, rhythm; the flexibility of this form allows poets to use language in whatever ways seem appropriate to their purpose, and to create the effects they desire in the work

Open form poetry is sometimes regarded as formless because it is unlike the strict forms. They still rely on an intense use of language to establish rhythms and relations between meaning and form. Open form poems use the arrangement of words and phrases on the printed page, pauses, line lengths, and other means to create unique forms that express their particular meaning and tone.

prose poem – printed as prose and represents most clear antithesis of fixed form

found poem – an unintentional poem discovered in a nonpoetic context, such as a conversation, news story, or an advertisement; playful reminders that the words in poems are very often the language we use every day

Classifying patterns allows us to talk about the effects of established rhythm and rhyme and recognize how significant variations from them affect the pace and meaning of the lines. An awareness of form also allows us to anticipate how a poem is likely to proceed.

stanza – group of lines, set off by a space; usually has a set pattern of meter and rhyme

rhyme scheme – pattern of end rhymes

tercet – three-line stanza

triplet – three line stanza where all lines rhyme

terzarima – interlocking three-line rhyme scheme: aba, bcb, cdc, etc.

quatrain – four-line stanza; the most common stanzaic form in English language

Other poetic techniques

enjambment (aka run-on line) – verse runs from one line to another due to grammatical structure; often,

punctuation elsewhere in the line reinforces the need to run on at the end of the line

end stop – grammatical break coincides with end of line

caesura – a break or pause in a line of verse; very important in influencing the rhythm of the poem

rhetorical devices which influence structure: anaphora, chiasmus, antithesis, apostrophe, zeugma, etc. syntax spacing, indentations, punctuation

Conventions of sound in poetry

Rhyme

Rhyme affects the sound and overall effectiveness of a poem. A rhyme scheme can unify a poem, give it an incantatory quality, or add emphasis to particular elements of vocabulary.

complete rhyme – exact rhyme at the end of a line

eye rhyme (sight rhyme, half rhyme, slant rhyme, para-rhyme, approximate rhyme) – “love” and “move”

internal rhyme – rhymes within the line of poetry

Rhyme can:

make a poem sound musical and pleasing to the ear

create a jarring, discordant effect

add emphasis to certain words and give particular words an added prominence

act as a unifying influence on the poem, drawing it together through the rhyme patterns

give the poem a rhythmic, incantatory, or ritualistic feel

influence the rhythm of the verse

provide a sense of finality – the couplet, for example, is often used to give a sense of “ending”

exert a subconscious effect on the reader, drawing together certain words or images, affecting the sound, or adding emphasis in some way

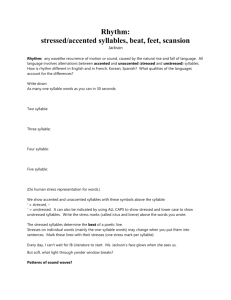

Rhythm

Rhythm can help create mood and influence tone; it can give a poem its feeling of movement and life. The rhythm of poetry can be influenced by factors such as word order, length of phrases, or the choice of punctuation marks, line and stanza breaks, and the use of repetition.

“Rhythm might be described as, to the world of sound, what light is to the world of sight. It shapes and gives new meaning.” – Edith Sitwell

stress (or accent) – places more emphasis on one syllable than on another (“You put the wrong emphasis on the wrong syllable.”)

syllable stress – natural rhythm of word

emphatic stress – shifted stress on a word to emphasize a particular meaning or reinforce a point

Meter

This is the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry. Variations in the pattern could mark changes in mood or tone, or signify a change of direction in the movement of the poem. The four basic kinds of rhythmic patterns are:

quantitative – rhythm established by patterns of long and short syllables; classical meter

accentual – the occurrence of a syllable marked by stress or accent determines the basic unit regardless of the number of unstressed or unaccented syllables surrounding the stressed syllable

syllabic – the number of syllables in a line is fixed, although the accent varies

accentual-syllabic – both the number of syllables and the number of accents are fixed or nearly fixed; when the term meter is used in English, it often refers to accentual-syllabic rhythm

foot – a group of syllables within a line of poetry o monometer – one foot o o dimeter – two feet trimester – three feet o tetrameter – four feet

scansion – the process of identifying the meter o stressed syllable:

o o o unstressed syllable: ˘ feet divider: │ caesura: ║

The five basic patterns of stress: o o o o pentameter – five feet hexameter – six feet heptameter – seven feet octameter – eight feet o o o o iambic – one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one (iamb); example: again trochaic – one stressed syllable followed by one unstressed (trochee); example: baby dactylic – one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed (dactyl); example: horrible anapestic – two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable (anapest); example: go along o o o spondaic – two stressed syllables (spondee); example: black night rising meter – moves from unstressed to stressed syllables falling meter – moves from stressed to unstressed syllables

blank verse – unrhymed iambic pentameter

masculine ending – line ending with a stressed syllable

feminine ending – lines ends with an extra unstressed syllable

Scanning a poem

These suggestions should help you in talking about a poem’s meter.

1.

After reading the poem through, read it aloud and mark the stressed syllables in each line. Then mark the unstressed syllables.

2.

From your markings, identify what kind of foot is dominant (iambic, trochaic, dactylic, or anapestic) and divide the lines into feet, keeping in mind that the vertical line marking a foot may come in the middle of a word as well as at the beginning or ending.

3.

Determine the number of feet in each line. Remember that there may be variations; some lines may be shorter or longer than the predominant meter. What is important is the overall pattern. Do not assume that variations represent the poet’s inability to fulfill the overall pattern and phrases or disrupt your expectation for some other purpose.

4.

Listen for pauses within lines and mark the caesuras; many times there will be no punctuation to indicate them.

5.

Recognize that scansion does not always yield a definitive measurement of a line. Even experienced readers may differ over the scansion of a given line. What is important is not a precise description of the line but an awareness of how a poem’s rhythms contribute to its effects.

Image from Purdue OWL