The State University of New York

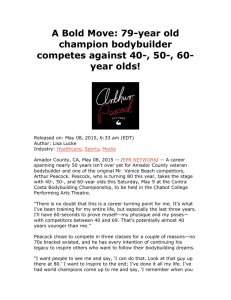

advertisement