ff8im_sec_02

advertisement

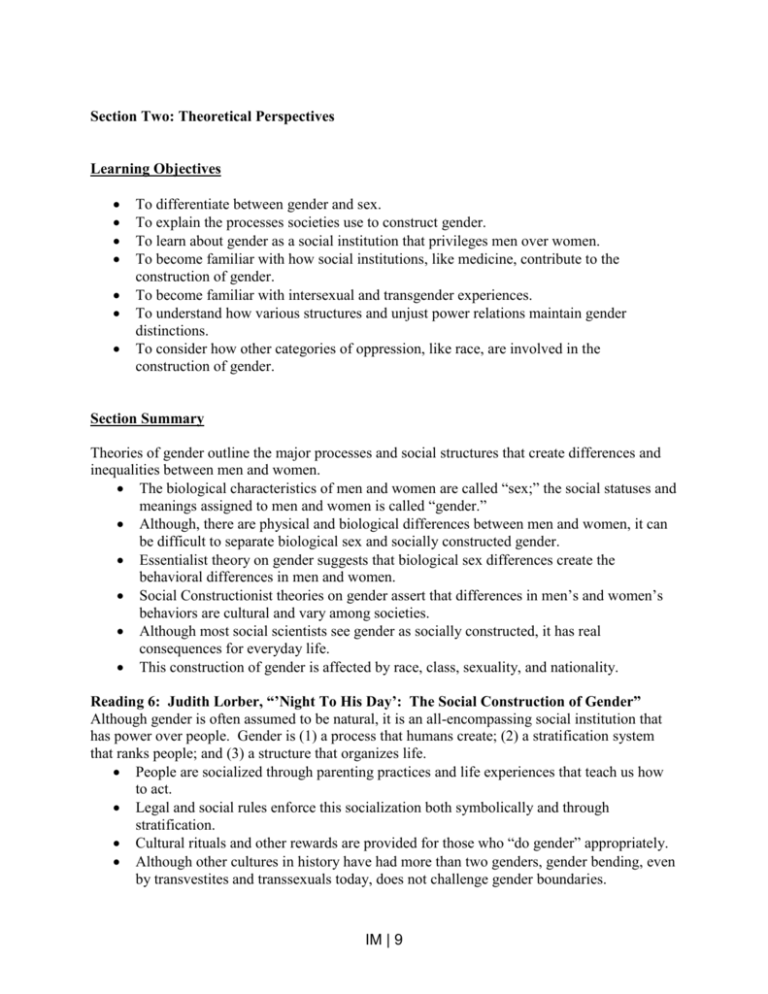

Section Two: Theoretical Perspectives Learning Objectives To differentiate between gender and sex. To explain the processes societies use to construct gender. To learn about gender as a social institution that privileges men over women. To become familiar with how social institutions, like medicine, contribute to the construction of gender. To become familiar with intersexual and transgender experiences. To understand how various structures and unjust power relations maintain gender distinctions. To consider how other categories of oppression, like race, are involved in the construction of gender. Section Summary Theories of gender outline the major processes and social structures that create differences and inequalities between men and women. The biological characteristics of men and women are called “sex;” the social statuses and meanings assigned to men and women is called “gender.” Although, there are physical and biological differences between men and women, it can be difficult to separate biological sex and socially constructed gender. Essentialist theory on gender suggests that biological sex differences create the behavioral differences in men and women. Social Constructionist theories on gender assert that differences in men’s and women’s behaviors are cultural and vary among societies. Although most social scientists see gender as socially constructed, it has real consequences for everyday life. This construction of gender is affected by race, class, sexuality, and nationality. Reading 6: Judith Lorber, “’Night To His Day’: The Social Construction of Gender” Although gender is often assumed to be natural, it is an all-encompassing social institution that has power over people. Gender is (1) a process that humans create; (2) a stratification system that ranks people; and (3) a structure that organizes life. People are socialized through parenting practices and life experiences that teach us how to act. Legal and social rules enforce this socialization both symbolically and through stratification. Cultural rituals and other rewards are provided for those who “do gender” appropriately. Although other cultures in history have had more than two genders, gender bending, even by transvestites and transsexuals today, does not challenge gender boundaries. IM | 9 Despite the countless ways gender could be constructed, societies try to make all biological boys perform the same gender as males and all biological girls perform the same gender as females. Women are demeaned because they are seen as lacking the characteristics of men that society privileges. Reading 7: Suzanne Kessler, “The Medical Construction of Gender” Kessler proposes that even biological sex distinctions between men and women are socially constructed. By looking at the medical community’s and parents’ treatment of intersexed children, she demonstrates that decisions about sex depend, for the most part, on social factors. Kessler uses six interviews with intersexuality experts in the medical community to reveal how the strict dichotomy between two sex categories (male/female) is maintained. Despite the existence of a variety of intersex categories, physicians promote the socially constructed idea that there are two distinct sexes by altering the bodies of intersex children. Doctors act as though they can determine the “real sex” of the child and subject the child to various medical tests during the initial months of the child’s life. Physicians decide which sex the child will be made to fit largely based on penis size at birth, and whether this organ responds to testosterone. Physicians normalize the existence of the intersex child to their parents by (1) teaching parents about fetal development; (2) stressing the “normal” aspects of the baby; (3) insisting that it is not the gender of the child that is ambiguous but the genetics that are ambiguous; and (4) stressing the social over the biological nature of gender. Physicians often try to ensure that intersexed children develop a socially acceptable gender identity by using lies and manipulation of parents and children. Reading 8: Susan Stryker, “Transgender Feminism: Queering the Woman Question” Stryker describes how bringing transgender phenomena into mainstream feminism and women’s studies will 1) transform this activism and scholarship by making obvious the structures of domination and control; 2) make justice more possible; and 3) bring together queer and feminist projects in productive ways. Transgender feminism focuses on the importance of the body and embodied experiences while describing gender as a series of possible configurations and positions. Stryker defines transgender as “a way of being a man or a woman, or a way of marking resistance to those terms” (p.88) and “transgender phenomena” are broadly defined as “anything that disrupts or denaturalizes normative gender, and which calls our attention to the processes through which normativity is produced and atypicality achieves visibility” (p. 85). Gender is a mechanism of domination. Transgender stigma, which strips away or misattributes a person’s gender, has been used as a form of social control to limit how people demonstrate their gender identities. Second wave feminism, particularly cultural and lesbian separatist feminism, was transphobic and even worked to erase the history of the transgender movement. Transgender issues are important to feminism because 1) it offers a revisionist history of feminism, 2) it engages many of the prominent questions in the social sciences and IM | 10 humanities and 3) postmodern or poststructuralist scholars have used transgender examples as evidence for their theories and conclusions. Transgender feminism suggests that socially constructed hierarchies are based upon bodily differences. Understanding transgender examples of nonconforming genders can disrupt the power structures behind various oppressions and privileges. Transgender practices and identities highlight the contradictions in gender, sex, and sexuality. Although the numbers of transgender individuals may be small, articulating transgender issues taps into issues faced by all of the subgroups (racial, economic, sexual identities, etc) within feminism. Additionally, transgender issues bridge feminist/gender studies and queer studies. Reading 9: Maxine Baca Zinn and Bonnie Thornton Dill, “Theorizing Difference from Multiracial Feminism” The authors highlight race’s significance in how gender is organized and experienced in a framework called “multiracial feminism.” This perspective examines how race and racial hierarchies influence our understandings of gender. The experiences of women of color were excluded from early theories of gender; the authors propose multiracial feminism as a framework that underscores how race and class are systems of inequality that shape gender. Multiracial feminism goes beyond recognizing the diversity of women’s experiences to understand how these differences are maintained by structures of domination. Women and men are affected by their location in structures of intersecting inequality, particularly race and class that intersect and determine how people are discriminated against and/or privileged. Race, class and gender intersect, or combine in various ways, to produce social structures and social interaction. Women and men of all races are affected by the social construction of difference in peoples’ lives. People’s differences are connected in systematic ways that confer differing levels of power to groups based on race, class and other systems of inequality. Although race, class, and gender constrain human actions, people maintain agency and may resist or undermine these structures. Boxed Insert: Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, “Feminism and Disability Studies” The author suggests that more critical analysis of disability is needed. She suggests that New Disability Studies will challenge views of disability as oppressive and lesser and redefine disability as another form of human diversity that should be celebrated and incorporated into everyday life. Reimagining disability this way 1) demonstrates that disability occurs in every society and every family, and most every life, 2) helps people accept that fact, 3) pushes people to integrate disability into understandings of human experiences. Although diversity and biodiversity have become popular, there is a push toward body uniformity that devalues physical and mental variety in human beings. However respecting the diversity of human disabilities will value disabled people and make space for them in spaces and experiences. The disability/ability system legitimates an unequal distribution privileges and disadvantages based upon the body. IM | 11 Reading 10: Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “Feminism Without Borders” Mohanty uses an international perspective to describe how race, gender, class, sexuality and nation are interacting systems of power that disadvantage many, particularly those from the “Third World,” while privileging others. The globalization of economics and labor has connected people in hierarchal relationships where the “Third World,” and socioeconomic analysis must go beyond the nation-state. The “Third World” is made up of people from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East and people of color in the United States and Europe. Third World feminist struggles make up an “imagined community” where potential cultural and political alliances could challenge structures of racism, sexism, colonialism, imperialism, and monopoly capitol. Little comprehensive research exists on the struggles of Third World women. Instead they are often seen as deficient in comparison to white, Western women. Third World women’s potential political alliance lies in their struggles against exploitative structures and systems. Third World feminism focuses on the simultaneity of oppressions and the complex interrelationship between struggles against these oppressions. Additionally, Third World women are interested in rewriting history and politics based on the everyday experiences of people of color and postcolonial peoples. Reading 11: Bob Connell, “Masculinities and Globalization” There are multiple forms of masculinity that vary by historical time period, geographic location, race, and systems of domination. Although masculinities are particular to their “ethnographic moment,” there are also global aspects of modern masculinities. The global gender order specifies divisions of labor among countries and creates hierarchies that rank men and women in relation to their position in the world economy. Masculinities are constructed by groups and institutions and are actively produced through social interaction. Masculinity and femininity are produced together. Some forms of masculinity are hegemonic; these forms are the most honored desired and/or dominant forms of masculinity. Other types of masculinities are subordinated. Institutions like the global marketplace and the state are gendered. The globalization of many institutions has produced a world gender order. The world gender order started with imperialism and continues with the globalization of economies. Today there is a highly unequal and partially integrated world society. The culture and institutions of the North Atlantic countries are hegemonic in the world system. The export of these institutions defines masculinity and femininity and brings about specific gender practices. The world gender order is patriarchal; it privileges men over women. Colonialism and neo-colonialism subverted traditional gender orders of many indigenous peoples in each time period: conquest and settlement, empire and postcolonialism and neoliberalism. Today the hegemonic masculine form is the “trans-national business masculinity” which involves increased individualism and only a commitment to accumulation. IM | 12 Forms of masculinity are always open to change and challenge from individuals and groups. Boxed Insert: Alice Walker, “Womanist” Walker offers various definitions of a “womanist.” These definitions suggest ways that feminists of color are both similar to and distinct from white feminists. A womanist redefines women as good. A womanist is seen as only a shade different from a feminist. Love for herself, other women, and all people is central to a womanist. Discussion Questions Reading 6: Judith Lorber, “’Night To His Day’: The Social Construction of Gender” 1. 2. 3. 4. What does Lorber mean when she says “gender means sameness” and “gender means difference”? How does gender create differences between men and women? How does gender create sameness among all women and among all men? How are the genders ranked in a way that privileges men over women? What does this mean for our daily lives? Why does Lorber say that women who become men receive prestige, while men who become women lose it? How is this complicated by society’s stigmatization of transexuality? Lorber suggests that gender bending and passing between genders preserves gender boundaries. Do you agree? How might the gender bending of transsexuals and people who are transgender challenge society’s ideas about gender? Reading 7: Suzanne Kessler, “The Medical Construction of Gender” 5. 6. 7. 8. How many sexes do most people in Western societies believe there are? How do cultural understandings about gender affect the medical and parenting decisions regarding intersex children? What do doctors believe guides their decision about what the sex of the baby should be? On what do physicians base their decision regarding the sex of the child? How does this help explain the reasons people believe gender is a natural system of differences? How do physicians normalize the intersex condition of a child to the parents? How do the physicians’ practices maintain the secrecy and stigma of intersex? How do the doctors explain the condition to the child as the child grows up? Are the doctor’s actions misleading? Reading 8: Susan Stryker, “Transgender Feminism: Queering the Woman Question” 9. What does transgender mean? Do you agree with Stryker that transgender is not an identity? IM | 13 10. Why does Stryker believe that transgender feminism is so important? What are the three sets of concerns that transgender phenomena open up? Are there other ways that transgender issues transform feminism/women’s studies? 11. How do transgender phenomena focus feminism on embodied experiences? Why is this important? 12. How do the constraints of sex and gender affect your embodied experiences? How might transgender feminism challenge the social control you experience? 13. In what ways does transgender feminism make claims to justice? Do you think these claims encompass all of the groups that Stryker suggests? Reading 9: Maxine Baca Zinn and Bonnie Thornton Dill, “Theorizing Difference from Multiracial Feminism” 14. What is “multiracial feminism” as Baca Zinn and Thornton Dill see it? Where did it come from, and why was it developed? 15. Why do the authors see a “false universalism” in the category of “woman”? Whose experiences were left out? How does looking at the experiences of minority or poor women change the way that gender had been theorized? 16. There are a variety of ways that women are differentiated. Why do Maxine Baca Zinn and Bonnie Thornton Dill focus on race? What other categories do you think are systems of inequality that differentiate women’s experiences? 17. What do Maxine Baca Zinn and Bonnie Thornton Dill mean when they say that race and gender are “interlocking inequalities”? How does race affect the way women or men experience gender? How does class affect the experiences of gender? How does class affect race? 18. Baca Zinn and Dill suggest that race, gender, and class are all primary organizing features of our lives. If this is the case, how do people have agency? How is resistance or underling of these structures possible? Boxed Insert: Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, “Feminism and Disability Studies” 19. What does the author suggest New Disability Studies will do? Why is it important to study disability in this way? 20. Do you agree with Garland-Thonsom that disability is like gender and race? Are humans guilty of limiting biodiversity by changing or eliminating disabilities? Reading 10: Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “Feminism Without Borders” 21. Mohanty describes Third World women and Third World Feminism. Who are Third World women? What links them in this broad category? How are they often seen as “different” from the perceived norm of white, Western women? 22. What are “imagined communities”? How are they created? What is the difference between an imagined community and a social category? 23. How do you think it will be possible to create a global feminism? What types of issues should this feminism look at? IM | 14 Reading 11: Bob Connell, “Masculinities and Globalization” 24. What are some of the recent lessons about masculinity from ethnographic research that Connell describes? 25. What types of masculinities developed during colonization/settlement? What types developed during the empire stage? What about now during postcolonialism/ neoliberalism? How are the masculinities of the three stages of globalization different? How are they similar? 26. How does the globalization of trade, labor, and markets influence masculinities? Can you think of ways that it influences femininities? Boxed Insert: Alice Walker, “Womanist” 27. How does the womanist point of view differ from the feminist point of view? 28. How does the womanist point of view relate to the standpoint theory used by Hill Collins in Reading 8? Assignments and Exercises Sex/Gender Distinction: This exercise can be useful, since many students have difficulty distinguishing between sex and gender. Provide students with the following list or a similar list. Ask whether each item is determined by sex or gender. Ask students to defend their answers. Continue to discuss why we sometimes believe these to be biological factors, when they are socially constructed. A. dressing girls in pink and boys in blue B. boys behaving aggressively and girls behaving passively C. the military Special Forces is mostly men D. more women than men stay home with their children E. the two categories of men or women F. women have to wear shirts in public; men do not G. sex organs Understanding Trans: Lorber’s piece has been consistently criticized for its treatment of people who call themselves “transgender” or “transsexual, and students may be curious about this group of people after reading Stryker’s piece. Hand out the Gender Education and Advocacy resource “Gender: A Primer” to students. Ask students to make a list of assumptions Lorber makes about “transsexuals” and “transvestites.” Now ask students to compare these assumptions to the information on the handout and to what Stryker says. The handout may be found at the website: http://www.gender.org/resources/dge/gea01004.pdf Imagining Intersex Children: This exercise is designed to have students put themselves in the position of the parents or children in Kessler’s piece in order to better understand intersexuality. Ask students to imagine that they have just had a baby. Ask them what they expect will be the first thing the doctor will tell them. Now ask them to imagine the baby has intersex characteristics. What would they want to do about this? Finally, ask students to imagine that IM | 15 they are intersexed young adults whose bodies have been put through many surgeries and hormone treatments in order to fit into a rigid sex category. How would they feel about their body, the doctors, and their parents? Trans and Intersex Activism: Students should understand that there are advocacy groups for people who challenge the categories of gender. Have students explore the Web for sites such as: http://www.gender.org http://www.isna.org/ http://www.gpac.org/ Ask students to describe how these groups actively challenge the binary categories of male and female. What kinds of problems do people who are trans or intersex face? What are these groups doing to ameliorate these problems? Library Exercise: Theories of Gender Academic journals print articles that explore a wide variety of topics relating to gender. Students should go to the library or access their library’s journal on-line. Students should write a one-page summary of the article they choose from a journal that specializes in issues of gender. The writeup should discuss what theory the author(s) use and how it relates to one or more of the articles in Section Two. Here are a few of the journals that students may choose to focus on: Men and Masculinities, Gender and Society, Genders, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Gender, Technology and Development, International Journal of Gender Studies, Feminist Theory, and Feminist Criminology. Globalization of Masculinity and Femininity In class show clips from a variety of popular movies from around the world, pass around popular magazines from different countries, or show commercials from multiple locations. Ask students to think about the many portrayals of masculinity and femininity. What are the similarities? How do these portrayals vary by race or geographic location? Do these portrayals indicate a hegemonic form of masculinity or femininity? Can students see a pattern that indicates a gender hierarchy? Thinking About Intersectionality Many of the authors in Section Two describe how gender affects people’s lives in concert with race, class, and other hierarchies. Ask students to describe how race (or class) affects the everyday gendered activities such as getting ready for work or school, attending school or working, or shopping. What lessons does this provide for thinking about the theories in Section Two? Using Popular Movies to Demonstrate Intersectionality Popular movies can provide a visual example of the intersectionality of gender, race, and class. Movies can be shown in class or excerpted to help students think about how race, class, and gender are interconnected. Suggested movies: Bend It Like Beckham, Real Women Have Curves, Bread and Roses, Girlfight, and The Color Purple. Web Links IM | 16 African-American Women African-American women have made many important contributions to social change and to social theory. These two websites provide brief introductions to the accomplishments of black women and to scholarship on black feminist thought. www.library.ucsb.edu/blackfeminism/index.html www.cddc.vt.edu/feminism/AfAm.html Intersex Society of North America Although many take human sexual dimorphism—the division of the species into two sexes—for granted, the existence of intersexed persons challenges the belief that human bodies are naturally only male or female. In recent years, the Intersex Society of North America has become a strong advocate for the rights of intersexed people. Read about their interesting work on their website. www.isna.org/index.html Isis International Manila This feminist organization seeks to expand knowledge about and for women, particularly those women of the global South. Women’s problems and opportunities are dependant upon their geographic location and their race. The publications and the advocacy of Isis reflect the insights of women from these regions. http://www.isiswomen.org/ Gender Education and Advocacy Transsexual peoples’ experiences are discussed by Judith Lorber in Reading 6. This website explores transsexual and transgender issues in much greater detail. Think about how trans people challenge or reinforce gender norms. What particular oppressions do they face? http://www.gender.org Gender Public Advocacy Coalition Gender stereotypes often cause people to act in violent or discriminatory ways. Gender Public Advocacy Coalition provides information and advocacy against gender discrimination. Follow some of the links to recent news stories to see how gender stereotyping continues to limit people’s opportunities. http://www.gpac.org/ Nation Center for Transgender Equality This organization uses advocacy, collaboration and empowerment to achieve equality for transgender people. This website provides information on legal and political issues facing transgender Americans, and suggests ways that individuals may take action on these issues. http://www.nctequality.org/ The Society for Disability Studies The Boxed Insert on feminism and disability describes disability studies as an important challenge to mainstream understandings of disability as something that is bad, lesser, or in need of change. This organization’s Mission Statement explains that the group’s purpose, “through research, artistic production, teaching and activism, the Society for Disability Studies seeks to IM | 17 augment understanding of disability in all cultures and historical periods, to promote greater awareness of the experiences of disabled people, and to advocate for social change.” www.disstudies.org/ The Transsexual Menace Judith Lorber describes transsexuals, but many transsexuals see themselves differently than she describes. The Transsexual Menace, an activist organization devoted to addressing the social and political challenges facing trans people, spells out some of the difficulties of transitioning from one sex to the other. http://www.themenace.net/ XY: Men, Masculinities, and Gender Politics Many discussions about gender focus on women. However femininity is constructed in relation to masculinity. It is important to look at how masculinities are formed, operate, and affect our lives. This website provides links to many articles about masculinity and its intersection with other categories of difference. There is also a bibliography on a variety of topics on men and links to other interesting websites on masculinity. http://www.xyonline.net/index.shtml IM | 18