Haiku

advertisement

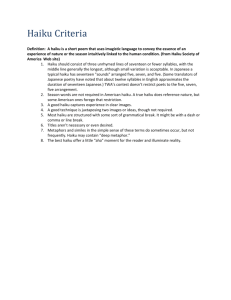

Haiku. 06.17.07 HUEN 3100 Author: Dr. Leland Giovannelli Haiku: Brevity in Image Earlier this semester, you encountered Aristotle’s ideas on the imitation inherent in Tragedy. We discussed his ideas as they applied to Oedipus, and then adapted them to English and American poetry. Now we will turn to a minimalist form of Japanese poetry—haiku—and ask some of the same questions: does Aristotle’s typology apply here? Of what is haiku imitative? Are the terms Character and Plot at all relevant to haiku? If not, can we find appropriate terms in which to discuss it? I. Historical and Theoretical Introduction1 The haiku style of poetry—the shortest poetic form in world literature—was developed in Japan about 500 years ago and perfected about 300 years ago. It is still popular. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese are serious haiku writers, and thousands of haiku clubs and magazines currently flourish in Japan. (In Japan reading haiku is considered as much of an art as writing them.) Western writers encountered haiku in translation at about the beginning of the 20th century, and interest in this poetic form spread to all parts of the Western as well as the Eastern worlds. Outside of Japan, the largest and most active community of haiku poets works in English. Haiku exemplify many aspects of almost all traditional Japanese art: clarity, simplicity, understatement, focus on concrete detail, and avoidance of abstraction. In fact, haiku do not employ metaphor, simile, or symbol, and are generally not expressed in complete sentences. To this extent, haiku strongly differ from most traditional Western poetic styles. On the other hand, George Orwell’s advice to use “the fewest and shortest words that will cover one’s meaning” and to allow “the meaning choose the word, and not the other way about”2 are directly relevant to appreciating and writing haiku. II. What makes a poem a haiku? Probably the most widely accepted definition in English is that by poet Cor van den Heuvel: A haiku is a short poem recording the essence of a moment keenly perceived in which nature is linked to human nature. What distinguishes haiku is concision [i.e., conciseness], perception and awareness—not a set number of syllables. Here are two classic English examples. Read them slowly, carefully, and out loud several times. 1 2 pausing halfway up the stair— white chrysanthemums not seeing the room is white until that red apple Much of the material in this handout by Michael McNierney is based, with authors’ permission, on William J. Higginson, with Penny Harter, The Haiku Handbook (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1985). Further editing by LG. 2 George Orwell, “Politics & the English Language,” from Shooting an Elephant and Other Essays (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1946). 1 Haiku. 06.17.07 The list below articulates the traditional characteristics of this kind of writing. Characteristics of a Haiku 1. A haiku is a short poem, usually fewer than ten syllables in English, and usually, but not always, three lines long. You were probably taught in grade school to adhere to exactly 17 syllables in the three lines: 5-7-5. This syllable count perpetuates a serious mistake made by early translators of Japanese haiku.3 Forget the 5-7-5 count: it is arbitrary, wrong, and needlessly mechanical. 2. A haiku consists of an image, clearly and directly expressed, or upon two such images juxtaposed in a surprising or significant way. A haiku shows us something; it does not tell us. It presents; it does not describe. 3. A haiku is concerned with emotions. It may be a mixture of things like surprise and delight in noticing something one hasn’t noticed before, or it may be something indefinable like a mixture of awe, sadness, and joy. Whatever the emotions are, they are never directly expressed. A haiku achieves its effect through suggestion and nuance. More is left up to the reader’s imagination than in most other forms of poetry. For example: This is not a haiku: I was sad when I saw the dead cat This is a haiku: 3 dead cat… open mouthed to the pouring rain 4. A haiku usually involves the author’s perception of and interaction with something in nature. 5. It is concerned with the here and now, and is almost always written in the present tense, even if it is about the past. The past is gone, but the act of remembering is in the present. 6. It uses no metaphors, similes, symbols, abstractions, or generalities. 7. A haiku involves all the senses, although not necessarily all in the same poem. 8. In haiku, complete sentences are not required; in fact, they are often not used because they can detract from the desired economy of language. 9. As short as it is, a haiku in English is often composed of two parts separated by a dash, a colon, an ellipsis (…), or extra space. These indicate a pause, which may be the unspoken connection between two images. 3 Japanese is a very different language from English or any other Indo-European language. Japanese words do not have syllables in the English sense but are composed of onji, which means “sound symbols.” Onji are considerably shorter than English syllables. In some Japanese words, it takes two or three onji to write what we would think of as one syllable. For example, take the word manyôshû. How many syllables does it have? Most of us would say 3: man - yô - shû. But in Japanese, it is counted as 6 onji. Traditional Japanese poets count onji, not syllables. Haiku. 06.17.07 10. A haiku is meant to be shared. The writer shares his or her experience with the readers, who in turn bring their own experiences to their interpretation and enjoyment of the poem. III. Analysis of a haiku The following commentary demonstrates that although haiku are richly suggestive and allusive, interpretation of them is not arbitrary. It must be based on a careful reading of every word and its relationship to every other word, as well as to the intellectual and emotional response of the reader and to his or her own experience. On the other hand, not every responsible interpretation must be identical. 4 dusk from rock to rock a waterthrush These nine syllables… suggest a mountain and forest setting. The bird moves about in a deepening solitude. Its movement helps to call into image, into being, the movement of the stream, whose waters are evoked simply by the bird’s name…The thrush moves in mystery—for in the dusk it seems to appear here, then there, as if by magic. The essence of the bird is being revealed to us as much by what we don’t see as by what we do. The harsh “k” sounds of the words for the surrounding “inanimate” features of the landscape—dusk and rock—contrast with and help to isolate, because of its relative softness, the word “waterthrush,” which stands for the only spot of life in the gathering darkness. Yet the iambic flow of the line, combined with the bird’s unifying movements, draws everything together into a whole in which the bird is not alone at all, but is one with rock, water and dusk—one with existence—and we are too.4 IV. Japanese classics Matsuo Bashô (1644-1694) was born into the samurai class (the upper, warrior class) but devoted his life to Zen Buddhism and poetry. Although he didn’t invent haiku, he turned it from what had become a trivial, superficial form of light verse to something much more profound. He is considered Japan’s greatest poet (having something like the place of Shakespeare in our culture) and has influenced every haiku poet in every language down to the present day. Many of his poems express a sense of the mystery of life and the universe. His poem about the frog is the most famous poem in Japan and the best-known haiku in the world. 5 6 8 7 old pond… a frog leaps in water’s sound on a barren branch a raven has perched— autumn dusk 9 the rough sea— stretched toward Sado Isle the Milky Way the stillness— soaking into stones cicada’s cry 10 the bird flies out and vanishes— the lone island not even a hat in the cold rain— ah, so what? Cor van den Heuvel, “Concision, Perception, Awareness—Haiku,” New York Times Book Review, March 29, 1987. 4 Haiku. 06.17.07 Yosa Buson (1716-1784) was an influential painter, and many of his poems reflect the visual, sensual, and objective qualities of an artist. By his day, the poetry of Bashô’s followers had declined in quality, and he went back to the master himself for inspiration. 11 12 the coolness— the voice of the bell as it leaves the bell 14 13 spring rain: an umbrella and a coat go chatting together 15 on the temple bell fast asleep— a butterfly in shimmering air— insects I can’t name whiteness floating 16 peony falling— dropped overlapping two or three petals I’m going you’re staying: two autumns V. Your own reading. Do not rush. Let the image(s) soak into your mind, without analyzing them; be aware of what feelings and associations come up for you. Later, read them again in light of the following questions. Make notes of your answers. 1. What are the images in each poem? What senses created them? What emotions emerge from them? What experience of the poet does the poem capture? To what experience of your own does it speak? 2. Haiku has been called “an open door that looks shut” and “a wordless poem.” How can you relate these descriptions to the poems you read? VI. Writing Haiku. When it comes time to write haiku of your own, don’t worry; just try. Writing haiku, like any art, takes a great deal of time and practice to master. Bashô said that if a person writes two or three really good haiku in his lifetime he is a haiku poet; if he writes ten, he is a master. Poets or Translators of numbered haiku 1. Elizabeth Searle Lamb 2. Anita Virgil 3. Michael McClintock 4. John Wills 5. trans. William Higginson 6. trans. William Higginson 7. trans. William Higginson 8. trans. Makoto Ueda 9. trans. M. McNierney 10. trans. M. McNierney 11. trans. R.H. Blyth 12. trans. R.H. Blyth 13. trans. Yuki Sawa 14. trans. Hiag Akmakjian 15. trans. William Higginson 16. trans. M. McNierney Henley: Invictus. 06.15.07 Henley: Invictus. 06.15.07 Invictus William Ernest Henley (1849-1903) Out of the night that covers me, Black as the Pit5 from pole to pole, I thank whatever gods may be For my unconquerable soul. In the fell6 clutch of circumstance I have not winced nor cried aloud. Under the bludgeonings7 of chance My head is bloody, but unbowed. Beyond this place of wrath and tears Looms but the Horror of the shade,8 And yet9 the menace of the years Finds, and shall find me, unafraid. It matters not how strait10 the gate, How charged11 with punishments12 the scroll,13 I am the master of my fate; I am the captain of my soul. 5 The Pit: the Pit of Hell. Fell: fierce, cruel, deadly. 7 Bludgeonings: brutal beatings. A bludgeon is a short stick, especially one with a weighted end, used as a weapon. 8 The shade: the land of shadow; the underworld; Hades. 9 Yet can mean still, to describe something that persists in time. 10 Strait: narrow (as in Strait of Gibraltar). 11 Charged: filled. (Compare, in speaking of guns: a charge of shot, a discharged revolver, etc.) 12 Punishments: not necessarily the legal consequences of evil deeds, but rather simply hardships endured. Compare with “punishing blows” endured by a boxer. 13 Scroll: roll of paper, papyrus, parchment, etc., used for writing; in this context, especially: the scroll on which one’s destiny is written. 6